Feature

Cattle Raised for Beef Are Heavier Than Ever, Raising New Concerns in the Industry About Animal Health and Welfare

Food•2 min read

Reported

Big Ag didn't just put small farmers out of business. They changed a way of life in rural America and made it harder to fight climate change.

Words by Max Steiner

On more mornings than he can bear, Nick Schutt nails sheets of plywood over his windows to keep the stench of livestock waste from settling into his basement. On the worst days, he just has to get up and leave, making the 5-mile drive from his place near Williams in Hardin County, IA, to his parents’ 80 acres. On the way, he counts the factory farms as they pass by, into double digits: 26 within a few miles of his home. The closest, 1,900 feet from his bedroom window, packs 2,500 head of cattle, along with the manure that collects and rots in subterranean pools for months at a time. Even at his parents’ place he often can’t escape the smell.

Many concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) go up next to neighbors who were never asked for permission. They realize what’s going on only when the county begins to dig the drainage ditches that funnel waste to local waterways—in Hardin County’s case, the Iowa River’s south fork. Some factory farm owners promise to install windbreaks like screens or trees, or even electrostatic fences, to control particulates and odor, but they rarely follow through.

When the industrial crop and livestock producers at Summit Farms wanted to place a feeding operation just north of Schutt’s home, they promised they would maintain nearby roads that were worn down by feed trucks and manure haulers. “Should have had it in writing,” Schutt said, “because they sugarcoated things and to this day they still haven’t done what they said they were going to do.”

As CAFOs continue to creep into Hardin County, its population is seeping out. Four percent of residents left the area over the last 10 years. Three local schools closed down or merged with others, a trend repeated across the state so often that “it is difficult to know the specifics of the ending of each of them,” according to a local community project that tracks shuttered schools year-by-year based on the last time their sports teams showed up at district basketball tournaments.

The only hospital serving the county, Hansen Family Hospital, has seen its income from Medicaid reimbursements and donations shrink by more than 50 percent since it opened its doors to patients in 2014. Although funded in part by Jeff Hansen—owner of Iowa Select, the state’s largest hog producer—the hospital closed its obstetrics wing, and doctors there stopped delivering babies in 2019. Meanwhile, the multimillion-dollar business behind Iowa Select keeps birthing more than 5 million piglets every year.

From farrow to fork, hogs in these concentrated feeding operations see daylight only twice: first after weaning on their trip to be fattened, and again when shipped off to a meatpacker for slaughter. Until they reach their target weight of 260-280 pounds, their excrement drops through slats in the floor, decomposing in pools that send ammonia and 300 other volatile organic compounds into the air. Industrial ventilators expel the toxic gases that would otherwise kill the hogs in droves—but not before the animals, and workers, breathe in the foul air.

“It’s almost a burning sensation,” said Schutt, who used to work at one of Iowa Select’s operations. The company hired him on salary and initially assigned him a reasonable schedule but soon ratcheted up his hours without extra pay, let alone time and a half, which doesn’t apply to agricultural workers under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Iowa Select proudly calls pork production a “tough job, a messy job” and “always an every-single-day job.” But by the end of each week, having spent day after day working late in back-to-back breeding and farrowing units, Schutt was making barely enough to live on.

“It was one of the shortest jobs I ever worked,” said Schutt. When first hired on, he hoped he could take his experiences at Iowa Select and turn them into a career as a hog grower. “It wasn’t going to happen. It got to be one of the jobs I hated the most.”

Eventually, Schutt quit, troubled by the working conditions that ravaged even the hogs. “Sometimes if you have a barn with larger pigs, all of a sudden your mortality rate really goes downhill to where you have a lot of deads,” he said. “That’s because their lungs gave out, and as a worker you’re in there every day also.”

When hogs die, workers pile the carcasses into a dumpster they call the “dead box.” Holes in the container floor and sides let rainwater wash off secretions. The blood, feces, and urine that still bear the chemical signature of a hog diet rich in antibiotics seep into the ground and are picked up by the network of drainage pipes that run beneath fields, sending excess water into rivers and lakes. Every so often a truck comes through to collect the rotting hogs and haul them to a rendering plant.

The excrement, diluted with wash water, coming out of hog CAFOs in Iowa adds up to more than 10 billion gallons of liquid manure each year. Operators spread it untreated onto surrounding farmland, once in the spring when farmers plant crops and again in the fall after the harvest. In theory, the nitrogen in manure acts the way it does in synthetic fertilizers, promoting plant growth. But in practice, the sheer amount of nitrogen from both manure and commercial fertilizer overwhelms the soil’s ability to contain it. The excess invariably ends up in the aquifers that feed Iowa’s town wells and works its way down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, where it creates a notorious dead zone—a 6,500-square-mile patch of algal blooms that flare up and die down in sync with Iowa’s summer growing season.

A portion of the nitrogen overdose not consumed by plants or washed down waterways escapes into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas with 300 times the heat-trapping strength of carbon dioxide, molecule for molecule. Nitrous oxide constitutes over half of US agricultural emissions. Methane makes up the balance, some of which is the byproduct of microbes decomposing livestock manure.

Animal waste that’s stored in basements or in outdoor lagoons—earthen pits that can reach up to 14 Olympic swimming pools in size—expels enough methane to justify installing anaerobic digesters. At a price tag of $1.5 million apiece, these air-tight, temperature-controlled chemical reactors capture the gas and burn it as engine fuel or to generate electricity.

Schutt has put off testing his tap water for fear of what he might find. “There’s a well-testing program that the county does, but I’m scared to have my water tested,” he admitted. “I’m kind of consuming it with not wanting to know what’s in it. But I won’t feed it to my kids. I don’t want them drinking it.”

To handle the pollution coming down the Raccoon and Des Moines rivers, two of the main sources of drinking water for central Iowa, the Des Moines Water Works is doubling the size of its nitrate removal facility, which was the country’s largest such facility when it was built in 1991. Its eight turquoise-colored tanks process 100 million gallons of water per day. In April, the nonprofit group American Rivers included the Raccoon on its list of the nation’s 10 most endangered waterways.

The perennial stream of nitrogen jolts life back into soil that has become something of an empty shell. Herbicides cover ground and foliage on virtually every acre of corn, soybeans, and wheat, the three crops that occupy most of Midwest farmland. Insecticides and fungicides, although used less liberally, round out the chemical cocktail that selectively attacks pests rather than crops, but they don’t perfectly discriminate between their intended target and other organisms promoting earth-bound life.

Take a shovel to the soil and you won’t dig up earthworms, a farmer’s barometer of soil health, capable of burrowing more than 2,200 miles of channels per acre to aerate roots and improve water infiltration. A meta-study published in May highlights the damage that pesticides do to earthworms, sabotaging their biology and ability to function.

The US Environmental Protection Agency has effectively blinded itself to pesticides’ impact on soil organisms, which it gauges by using the European honeybee as the sole proxy for all terrestrial invertebrates. Conventional plowing, dominant on most US farmland though increasingly interspersed with periods of no-till, also decimates earthworms.

Pesticides and the seeds engineered to withstand them come as a package deal, because the companies manufacturing both products are by-and-large one and the same. In 2018 the German drug-maker Bayer paid $63 billion for the seed company Monsanto in a deal that survived intense antitrust scrutiny. Now Bayer is paying another $10 billion to settle claims that Monsanto’s weed killer Roundup causes cancer.

Nick Schutt is deeply troubled by the changes industrial agriculture has brought to the land and those who work it. There’s no trace of his home state’s oft-invoked “Iowa Nice” as he drives past the factory farms. Caring for the land and being neighborly turned into a marketing campaign long ago. “I guess I’m fighting my own mind trying to figure out why farming has become what it is today,” he said.

Barb Kalbach often points to the square mile surrounding her home to showcase how industrial agriculture hollowed out rural communities. She’s a fourth-generation farmer living near Dexter, about 80 miles southwest of Schutt. When Barb and her husband, Jim, started working the land in the 1970s, six families lived within a mile. Each had its own diversified lot of livestock and crops to tend to: some cattle or hogs, a few chickens, maybe a milk cow or two grazing on pasture alongside oats, hay, and the usual row crops of corn and soybeans.

“All of those people needed to buy repairs of parts and feed for their animals and had to call the veterinarian,” Kalbach recalled. “They would get their groceries and parts in town.” The farms’ demands and the families’ needs were folded into Dexter’s economy. Nearby towns hosted a strong network of barns and buying stations where small farmers could sell their livestock at competitive prices.

Money turned over seven times in any local community that supported livestock, so the saying went, because of all the ancillary businesses needed to raise animals, from feed suppliers and machine shops to meat lockers and farmers markets. Taxes went toward keeping schools open. A local dentist was available, and a small doctor’s office gave kids their shots and treated sore throats. For more serious interventions, Dexter had a town hospital.

“All of those are gone,” said Kalbach, whose family is the only one left within their square mile. Neighbors were driven out by the financial crisis that hit farms in the 1980s and the rise of industrial-scale farms since then. Some saw the crisis coming, given the boom and bust cycles the agricultural sector moves through as it tracks commodity prices. But few dared to imagine its severity.

Leading up to the crisis, rural America went through a dramatic shift in the scale of farming, as the US government encouraged farmers to expand production at all costs. A massive sale of wheat to the Soviet Union in 1972 caused domestic grain shortages and kicked open a seemingly insatiable export market. At the time, former Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz urged farmers to keep up with demand, calling on them to “get big or get out.” Government pressure, low interest rates, and generous loan guarantees encouraged farmers to take on staggering amounts of debt to finance ever-larger operations. At the close of the decade, the export market crashed, and crop prices tanked.

“That got rid of a lot of farmers,” said Kalbach. “Tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands across the country.” Bankruptcies rippled through the countryside at a higher rate than during the Great Depression.

“There was a responsibility of people in my department,” said John Ikerd, professor emeritus of agricultural economics at the University of Missouri. “We would go out and try and help these farmers. We’d go over their books with them trying to help find some way to survive or get them to sell out while they still had equity. Or at least talk them out of committing suicide.”

The farm crisis only further solidified consolidation as a survival tactic. As smaller farms went broke, their land was swept up by the few that kept gaining size. A frenzy of expand-or-expire set in. “I could see that we were caught in this trap of continual pressure to force farmers out of business and out of rural communities,” said Ikerd. “I could see that failure was built in.”

The logic of efficiency captured by Butz’s get-big-or-get-out mantra urged agriculture further down the path of greater specialization, a course that held even after the crisis had more or less stabilized. By 1995, Iowa was set for explosive growth in CAFOs when a state bill turned over permitting authority to the state’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR), an agency ill-equipped to make the transition from handing out fishing licenses and maintaining state parks to being the sole regulator of factory farming.

Since that time, Iowa has become a pork production powerhouse. Nearly one-third of the country’s hog inventory sits in Iowa, where hogs outnumber humans by 7 to 1. At least 90 percent are packed into concentrated animal feeding operations, each of which houses 1,500 head or more.

How many CAFOs are operating isn’t entirely clear even to the DNR. Ordered by the US Environmental Protection Agency to clear up the count, the department used satellite imagery to uncover some 5,000 off-the-record CAFOs of unknown size. It added some of these to its database, which now lists more than 10,000 CAFOs of all sizes. A disclaimer near the bottom reads: “The DNR cannot guarantee the accuracy and completeness of the available information.”

Today, two-thirds of Iowa’s hogs are raised on contract with the state’s largest meatpackers and sold to them at predetermined prices rather than on the competitive cash market. Dwarfed by the production rate of concentrated operations, independent farmers are left without the infrastructure they need to get a fair bid on their hogs.

“Within a 20-mile radius, there were three different places that you could call and get a bid for your hogs that are ready to go to slaughter, and then you could pick the best bid and take the hogs there,” said Kalbach. “Now there is no place to call.”

Nick Schutt is in the same situation. “There used to be a sale barn in every small town. And now for me to sell a cow I have to drive 75 to 100 miles unless we use some of that technology and sell it on Craigslist or Facebook marketplace. Somewhere private like that. We don’t have access to a huge hog market like we used to.”

“That’s kind of been the process since the ‘80s really, of the consolidation and the emptying out of rural America,” Kalbach said. “The draining of rural America is just about done. Just about done.”

Schutt’s neck of the woods, surrounded by CAFOs, and Kalbach’s square mile, now largely abandoned, showcase what farming has become: a highly specialized industry dominated by a handful of corporations with national and international reach, with little regard for their impact on the environment. In concert, they act much like a monopoly.

The USDA’s most recent estimates of the market shares held by the largest four US companies in each of five agriculture sectors are telling: beef—85 percent; pork—66 percent; corn seeds—85 percent; soybean seeds—76 percent; poultry—51 percent. To economists, these figures ring alarm bells. They’re past the tipping point at which the market slips into exploitative practices and price fixing.

In getting to such levels of concentration, the biggest meatpackers took control of every stage of production: hog-breeding genetics, farrowing and fattening operations, slaughtering and processing, even the trucking lines that distribute products. All are linked in a chain held tightly by individual corporations. Farmers are brought into the fold when they sign contracts to raise livestock on assignment, a production scheme that has dominated the chicken broiler industry since the late 1950s and began to capture hog farming in the mid-1990s.

Contracts grant farmers ownership of two things: the barn to grow livestock in and the manure that results. Corporations offload the cost of building high-tech barns, reaching into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, onto farmers who often go into debt to pay for them. Contract farmers don’t own the animals they raise, nor do they have a say in how to feed them or keep them healthy. In exchange, they are paid a monthly flat rate per pig space over the course of 10 to 12 years. The guarantee softens price fluctuations, but without a way to adjust for inflation they effectively take a pay cut each year. Over the length of a contract, the buying power of a contract farmer’s wages may shrink by more than 20 percent.

Meanwhile, markets once open to independent farmers who still own their own livestock have slammed shut. Today fewer than 7 percent of US hogs are sold by competitive bidding. As sales barns vanished, so did the farmers that relied on them.

For families like the Kalbachs and Schutts, working the land has long stopped being profitable. The yearly median income from farming activities per household stood at negative $1,735 in 2018 and in 2021 hovers just below $500. Most families rely on off-farm income to get by. Apart from farming, Barb Kalbach is a retired nurse, and Nick Schutt works at a waste transfer station.

Many independent family farmers see big agribusinesses as the first target in their line of attack against problems ranging from nitrogen pollution and greenhouse gas emissions to the siphoning of profits from rural communities.

“The first thing we need to do is break down these monopolies, go after them with antitrust. Everything else will become easier to address,” said Chris Petersen, who served three terms as president of the Iowa Farmers Union and is a board member of the Organization of Competitive Markets. In his 70s, he’s still farming, raising Berkshire pigs he sells from his home in Clear Lake, IA.

Breaking monopolies is not only good for fighting climate change, Petersen added. “It’s good for our rural America, it’s good for our culture out here, it’s good for the consumer, it’s good for addressing pollution, it’s good for food safety. You name it. But it ain’t gonna happen, until we really…” He pauses. “I tell everybody: I guess things need to get worse.”

Among the antitrust laws in question is the Packers & Stockyards Act, drafted after an investigation by the Federal Trade Commission found that meatpackers restricted the flow of food, fixed prices, and crushed competition—back in 1919. Over the act’s long lifespan, lax interpretation and watered-down enforcement have given agribusinesses free rein to concentrate so long as food prices to consumers didn’t hike as a consequence.

In 2018, the Trump administration dissolved the independent agency in charge of enforcing the act and shuffled it into the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service, which runs the program that fuels ad campaigns such as “Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner.” It routinely hemorrhages tax dollars into the coffers of trade associations that lobby against the interests of independent family farmers.

As secretary of agriculture, Tom Vilsack has significant influence over whether the USDA will crack down on anti-competitive behavior. His previous attempts in 2010, then secretary under President Barack Obama, to strengthen the Packers and Stockyards Act met with 6 years of industry-fueled resistance in Congress before the update was eventually withdrawn. Last month, the USDA announced it would try to revive that set of rules in the months ahead.

Petersen has seen administrations come and go without reaching the milestones he’d like to see. In many one-on-ones with Vilsack during the Obama years, Petersen laid out the realities of the countryside and the need for mandated rather than voluntary action. He still remembers Vilsack’s eventual assessment of the situation: “His response was, he looked at me, he said, ‘We’re never getting mandatory compliance on anything.’”

“I used to trust government to a certain degree,” Petersen said. “But they have ignored us. They have handed us over to the wolves, all my farming career.”

Schutt shares Petersen’s frustration at being brushed aside. “I don’t understand why it’s so hard for both parties to sit down and visit about what people really want and people really need,” he said. Two years ago he ran for the Hardin County Board of Supervisors to have a say in how the local government allocates taxpayer money, including to CAFOs asking for construction permits. The 34 percent of the vote he secured didn’t win him a seat on the board, and while he took hope from the support he did receive, he was shaken by a smear campaign against him.

“It seems like the more a person speaks out, the more of a dirty bird you are in the community,” Schutt said.

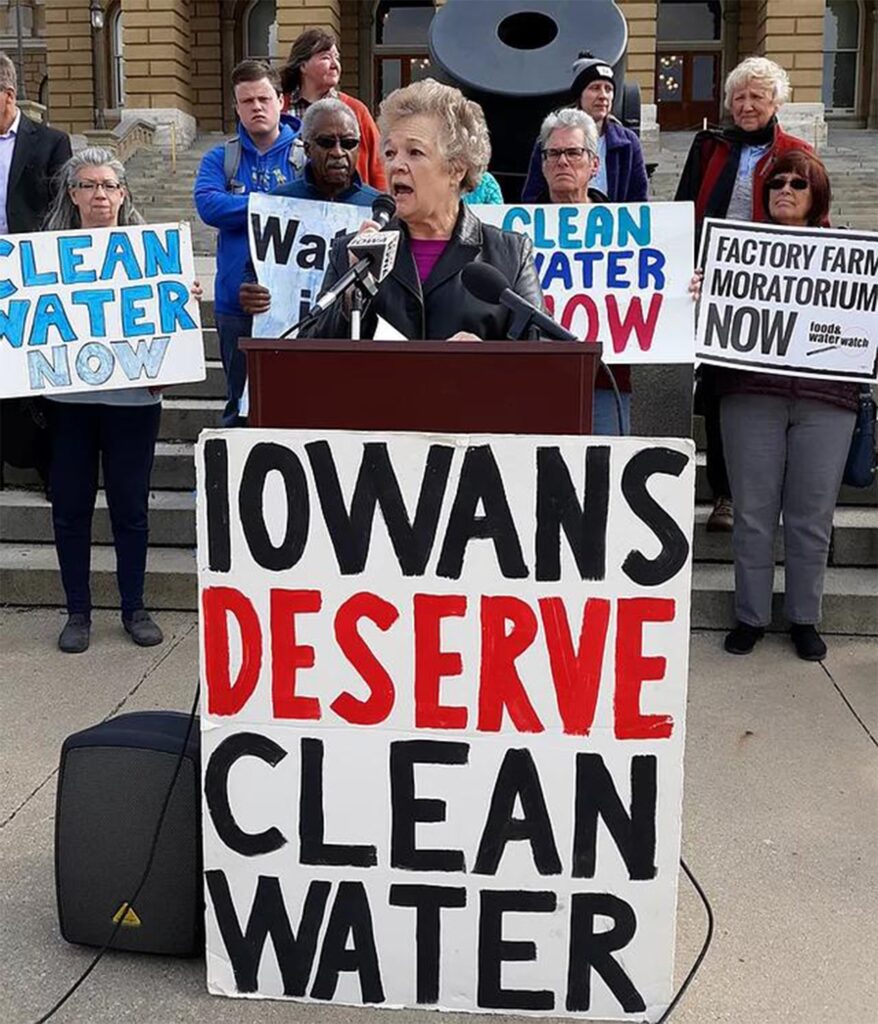

Meanwhile, the 30-groups-strong Iowa Alliance for Sustainable Agriculture, which Petersen co-founded seven years ago, makes sure there’s always a bill in the state legislature to put a moratorium on new CAFO construction. “We need a pause to figure out what the hell is going on and then to start to address these issues,” said Petersen.

Iowa’s Republican-controlled House, Senate, and governor’s office have so far shot down any attempts to change the way livestock is raised. Their resistance is fueled by campaign donations, especially from Bruce Rastetter, the meat and ethanol mogul who runs the Summit Agricultural Group, parent of Summit Farms. Rastetter, dubbed a “kingmaker” in media circles, has donated $1.5 million to Republicans at the federal and state level every year since 2003.

Independent family farmers face an uphill battle against corporations with bottomless budgets and market share to match.

“We just need help out here,” said Schutt.