Investigation

Homesteading Is a Viral Trend, but ‘Butchery Gone Awry’ Is Its Dark Side

Food•6 min read

Investigation

We investigated the animal welfare claims on Open Farm’s pet food labels and found they don’t live up to the hype.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

Americans love their pets. More than 65 million households own a dog, the most popular pet in the U.S., and 46.5 million homes own the next most popular pet, a cat. All of those animals eat a lot of food — U.S. pet owners spend $58.1 billion dollars per year on food and treats to keep their pets well-fed, in fact. And a growing number of pet owners want to be more discerning with that kibble, with an increasing share buying pet food marketed as “humanely raised.” But our investigation found just because a pet food brand markets itself as humanely raised doesn’t necessarily mean the animals are raised or slaughtered any differently.

One pet food brand, Open Farm, has been lauded by top-ten lists as a most sustainable or most ethical pet food brand, included among companies that use language like “cage-free” and “grass fed” on their labels. But Open Farm goes farther — it’s the first ever Certified Humane dog and cat food brand — marketing itself as “humanely raised” and “sustainably sourced.”

“Just as you want to give your pet the best life you possibly can,” reads Open Farm’s online mission statement, “we work diligently to ensure that the animals in our supply chain have a chance to live their very best lives, too.”

Much like greenwashing, a term used to describe false or overinflated marketing claims that a product is eco-friendly, humanewashing refers to marketing tactics that tout a product as more ethical than it really is. With both of these marketing ploys, companies make positive claims that are either overinflated at best, or at worst, completely inaccurate. They’re common on meat packaging, and that includes labels for pet food.

These tactics are common in part because they have been fairly successful. A 2018 nationwide survey of consumers found that “free-range” and “cage-free” increased intent to purchase by 14.8 percent and 15.8 percent, respectively.

This works with pet parents too. One market survey found 38 percent of U.S. consumers are looking for “all natural” pet foods, while 74 percent believe companies should be more transparent about their farming practices.

Cardiff University researcher Carly Baker analyzed Open Farm’s claims in a 2023 study, telling Sentient that she chose this specific brand due to the “certified humane” designation. Open Farm is far from the only company whose humane marketing doesn’t match how farm animals are actually raised. In fact, says Baker, “they are actually doing better than other companies.”

The majority of pet food comes from industrial meat production — around 30 percent of what’s leftover from processing and unsuitable for human consumption. Just like any other meat you find in the grocery store, it’s sourced from animals raised with minimal welfare standards and no regulatory oversight.

Looking into Open Farm, Baker found a lack of transparency and traceability in the company’s supply chain, despite the company’s messaging and Open Farm’s own traceability tool, advertised on each bag of food and accessible on the company website. As the site explains, the tool allows consumers to trace every ingredient back to its source. “We go to great lengths to find the best ingredients in the world, auditing every meat provider we work with to make certain they meet the highest standards. Sounds like a lot? We think it’s exactly what your pet deserves.”

But after randomly selecting a bag of chicken-based kibble and entering the numbers into the online tool, Baker was not in fact able to source just where the ingredients came from.

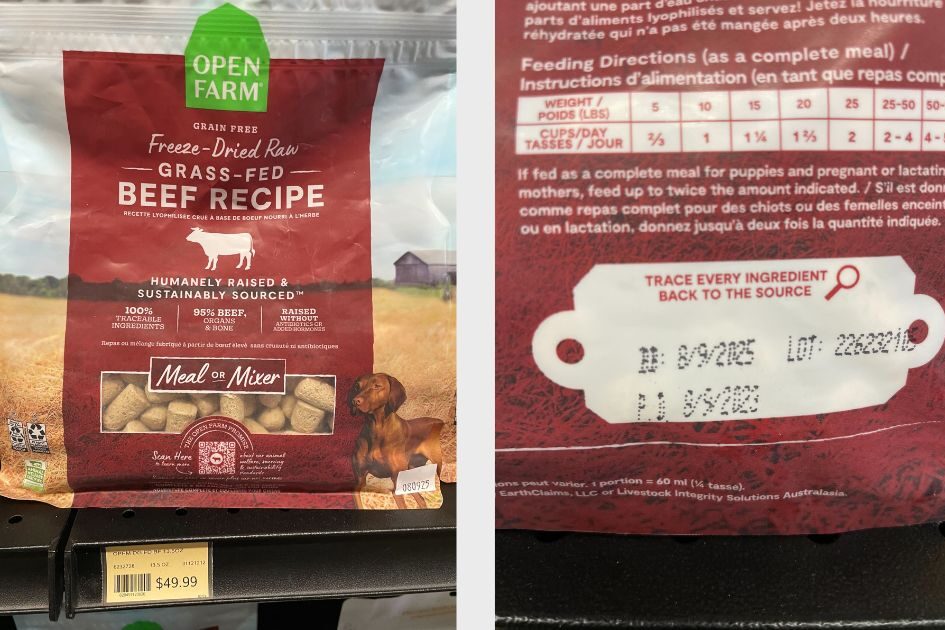

Sentient also used Open Farm’s online traceability tool to track a bag of “Grass Fed Beef Freeze Dried Raw Dog Food,” purchased from a store in Canada (where the company is actually based). After entering the lot number into the search bar, a date of production was provided, but no farm, state/ province, or any further details beyond certifications and ingredients were available.

Baker also found the tool generated a list of lot numbers, which “stated that the chicken came from Pennsylvania,” she wrote. But that didn’t go very far. “When I contacted Open Farm,” she wrote in the study, “they provided names of sheep and pig farms but were unable to identify any chicken farms.”

In her search for further details, Baker “browsed all 296 farms on the certified humane website and found one chicken farm in Pennsylvania, Murray’s Chicken.” She reached out to Murray’s Chicken to find out if they source to Open Farm, yet received no response. In other words, “Even though Open Farm tries to make the supply chain for meat consumption clear, it is still muddy. A truly transparent supply chain would ideally know the names of the farms for all farmed animals.”

Sentient contacted Open Farm about claims made in Baker’s research, as well as our own findings, and were initially contacted by public relations representative Alina Duviner. But Duviner later emailed to say she was “not able to engage the company,” and then was “unable to reach the company” for our story.

The Certified Humane program has different welfare standards for different farm animals species. “Cattle are required to have outdoor access, but chickens, turkeys, and pigs are not.”

The Open Farm website shows images of chickens playing outdoors on grass, along with the text “running freely.” The company has also signed on to the The Better Chicken Commitment, which sets a minimum standard of 1 square foot per 6 lb bird. Yet this is within the confines of a chicken shed, not outside on open grass, as the Open Farm marketing suggests.

When it comes to slaughter practices, Open Farm says the animals it sources are killed according to a standard written by longtime farm animal handling researcher Temple Grandin, PhD for North American Meat Institute (NAMI). This designation assures consumers that animal welfare standards, including handling, transportation and stunning methods, exceed the minimal standards set by the USDA.

Yet NAMI standards are already used by the vast majority of the industry, says Dena Jones, an animal welfare policy expert with Animal Welfare Institute. And while NAMI slaughter standards do not apply to chickens or turkeys — chicken slaughter standards are set by The National Chicken Council, and turkey slaughter standards are set by The National Turkey Federation — both of these are used by the vast majority of the industry.

In other words, says Jones, Open Farm “can’t say that their animals are being slaughtered under more humane conditions than for other products, because everybody is using the same standard.”

Throughout the meat industry, even the most stringent slaughter standards are only held accountable on an annual basis anyway, says Delcianna Winders, associate professor of law, and director of the Animal Law and Policy Institute at Vermont Law School. The bottom line, according to Winderss: “having a brief pre-announced inspection once a year for compliance — with guidelines set by the very industry being regulated — is no assurance that the animals in your dog or cat food were handled … or slaughtered humanely.”