Investigation

North Carolina Created Complaint Systems for Its Factory Farms. They Don’t Work Very Well.

Climate•11 min read

Analysis

A DeSmog review of hundreds of documents identifies eight arguments fielded by the industrial farming lobby to allay concerns over livestock drugs.

Words by Michaela Herrmann

Two years after landmark European Union legislation designed to curb the overuse of antibiotics on farms came into force, new analysis from DeSmog reveals eight key narratives the veterinary medicine and farming lobbies deploy to defend the billion-dollar market for the drugs.

Aiming to combat the emergence of deadly treatment-resistant bacteria in humans, known in medical jargon as “antimicrobial resistance,” or AMR, the new rules are the world’s most rigorous legislation governing farm antibiotics. The regulations banned the “routine” use of antibiotics on farms for whole herds of healthy animals, including outlawing the practice of using antibiotics to compensate for illnesses caused by poor animal welfare and hygiene.

As the focus turns towards implementation in the EU’s 27 member states, campaigners fear multi-national veterinary medicine companies will use the eight narratives identified by DeSmog across social media, government consultations, company reports, and other communications in an attempt to preserve annual sales of farm antibiotics, estimated to be worth $950 million in 2021, according to Grand View Research.

The narratives DeSmog identified after reviewing hundreds of industry communications are:

Reports that the animal farming industry has lobbied hard against animal welfare regulations in the EU, delaying the implementation of policies that have broad public support, have sharpened concerns that industry could also resist moves to reduce the use of antibiotics.

“Many of these arguments have been around for decades,” said Cóilín Nunan, a policy and scientific adviser to Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics, a coalition of health, sustainable farming, and civil society organisations. “Undoubtedly, these sorts of arguments are going to be made [at the member state level].”

The veterinary medicines industry dismisses concerns that it may resist implementation of the new rules, saying it is committed to building on reductions in the use of antibiotics on farms that have already been achieved, while continuing to tackle animal disease.

“The animal health sector strongly supports responsible use and reducing the need for antibiotics,” said a representative of HealthforAnimals, an industry group that represents U.S. drug makers Elanco Animal Health Inc., Phibro Animal Health Corp., and Zoetis Inc.

“Many markets have achieved significant reductions in antibiotic need by leveraging preventative veterinary health practices such as greater vaccination, better nutrition, improved biosecurity, and more,” the representative said. “More work will be done in the years ahead to continue tackling animal disease and reducing antibiotic need and we encourage others to learn from the successes achieved in animal health.”

Antibiotics are a pillar of the intensive farming systems familiar in many European countries, where the drugs have been used to prevent or treat outbreaks of disease among pigs, poultry, cattle, and other livestock kept in crowded conditions. Excessive use of antibiotics on farms is a major driver of AMR in people, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

More than 35,000 people die each year due to antibiotic-resistant infections in the European Union, Iceland, and Norway, according to estimates from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Without stronger policies to counter the emergence of new superbugs globally, the 700,000 deaths caused by antimicrobial resistance worldwide each year could grow to 10 million by 2050 – a number higher than the amount of people who currently die from cancer, according to a 2016 report.

In 2022, the EU took a significant step towards curbing excessive use of antibiotics by banning farmers from giving the drugs to large groups of healthy animals – seeking to achieve further reductions in the use of antibiotics, which has fallen by 53 percent from 2011 to 2022, according to official data covering 25 European countries. The EU also moved to protect the efficacy of “critically important” drugs by creating a reserve list of antibiotics for human use only.

Roxane Feller, the secretary-general of AnimalhealthEurope, a Brussels-based lobby group whose members include Elanco Animal Health Inc. and Zoetis Inc., said the veterinary medicines industry had been working with regulators on farm antibiotics for 30 years.

“There will be one day when they’re going to have to stop asking us to reduce because there is a limit to reduction. We’ve started to go down the hill for the last ten years of statistics – but there will be a time when the line will have to go straight,” Feller told DeSmog on the sidelines of the Animal Agtech Innovation Summit in Amsterdam in October.

“The objective is to continue to reduce, as long as it doesn’t affect animals. Because an animal who doesn’t get treated suffers. Nobody wants that,” Feller added. “The issue stays very high on the agenda of our companies. We are very conscious of the need to reduce antibiotics. It’s a real commitment, and really we are doing our share.”

Campaigners and academics fear, however, that elements of the veterinary medicines industry may deploy the eight narratives about the purported hazards of reducing antibiotic use to delay multiple stages of the complex implementation process.

The outstanding challenges include developing methods to accurately and consistently measure reductions in antibiotic use on farms; crafting a standardised antibiotic reduction plan for member states to adhere to; and navigating complaints from third countries – those that are not within the EU, but are subject to the antibiotic rules because they import products into the EU – that are pushing back against the rules.

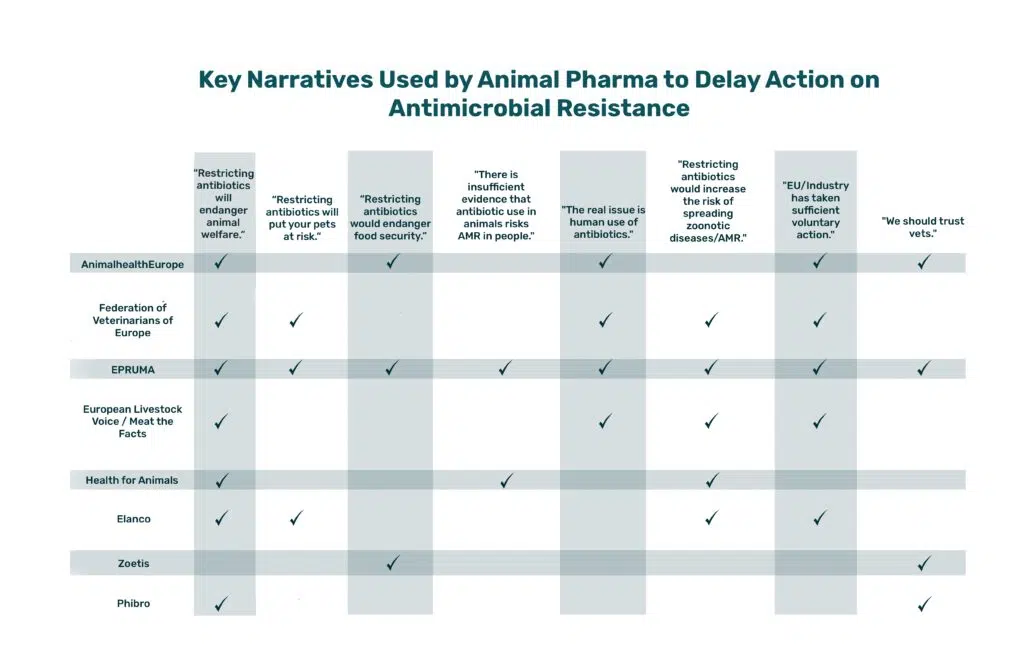

To identify common industry narratives, DeSmog evaluated more than 100 communications from five leading industry groups that represent animal pharmaceutical producers, livestock farmers, veterinarians, and other participants in the sector: AnimalhealthEurope, the Federation of Veterinarians of Europe, the European Platform for the Responsible Use of Medicines (EPRUMA), European Livestock Voice, and HealthforAnimals.

These groups represent pharmaceutical companies that manufacture animal antibiotics, including U.S. drug makers Elanco and Zoetis, Germany’s Boehringer Ingelheim, and France’s Virbac, as well as major industrial agriculture lobby groups such as Copa-Cogeca, which represents European farmers and agribusiness.

DeSmog also reviewed each group’s website, publications about antibiotics and AMR, social media posts, and submissions to the EU regarding antimicrobial policy.

We examined similar documents from Elanco, Zoetis, and Phibro, which are among the world’s biggest animal pharma companies. All three U.S.-based companies operate globally, and are therefore subject to stricter antibiotic regulations in the EU than other regions.

While the animal pharma industry’s narratives – which often mix science, industry preferences, and anecdotal evidence – are not outright falsehoods, they tend to oversimplify the reality of where the world currently sits on its journey to a post-antibiotic world, and downplay animal agriculture’s contribution to that reality, according to academics and campaigners interviewed by DeSmog.

“These narratives replicate common approaches of those who want to keep the status quo and avoid regulation,” said Jennifer Clapp, a professor of global food security and sustainability at the University of Waterloo. “They try to convey that a change in policy won’t work, that it will create the exact opposite of the intended outcome, and that it will jeopardise other goals.”

Like pesticide companies in Europe – which DeSmog found to have used similar “narratives of delay” to water down and sideline legislation requiring cuts to pesticide use – the animal pharma industry calls for more science before decisions are made; points the finger at human use of antibiotics; and claims that it is already doing enough to address the risk of antibiotic resistance.

“Companies, particularly tobacco and fossil fuels, have also regularly challenged the science of causation with claims that evidence is weak, insufficient, or uncertain,” said Jennifer Jacquet, professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Miami.

Despite stated commitments to reduce antibiotic use in their operations, none of the major animal pharma companies has adequate policies for addressing AMR, according to a 2021 report from FAIRR, a UK-based research network that aims to raise investors’ awareness of business risks in the global food system.

The report – which examined practices within the animal pharma industry that are “contributing to the growing risk of AMR” – looked at ten publicly listed animal health companies, including U.S. firms Elanco, Phibro, Zoetis, and Merck & Co., as well as companies based in the EU, such as Finnish Orion Corp. and French firms Vetoquinol and Virbac.

Here are the eight animal pharma industry narratives identified by DeSmog:

What the animal pharma industry says:

One of the most common narratives DeSmog identified is the argument that restricting antibiotic use would harm animal welfare and leave animals at risk of illness and disease.

The industry says that livestock and pets will suffer if a reduction in antibiotic use is mandated, because vets won’t be allowed to use antibiotics to treat individual infections or protect herds that have been exposed to an infected animal.

AnimalhealthEurope – which describes itself as the “voice of the animal medicines industry” – writes on the “focus areas” section of its website that while it may be “tempting to restrict antibiotic use to people only,” if animals are deprived of antibiotics “disease will spread and animals will suffer.”

Indiana-based Elanco echoes this sentiment: In a May 2023 video about antibiotic stewardship, the company’s Chief Medical Officer Dr Shabbir Simjee states that Elanco’s approach to antibiotic use is “not entirely on reducing antibiotic usage by compromising animal welfare,” adding that Elanco is focusing on reducing the use of shared-class antibiotics – those used to treat both humans and animals – in particular.

What campaigners say:

A crucial detail that many of the industry’s communications leave out: The most recent legislation in the EU never included an outright ban on using antibiotics to treat livestock animals. Rather, legislation placed antibiotics that are “critically important” for treating illnesses on a humans-only reserve list, to protect the efficacy of those medicines. Campaigners interviewed by DeSmog emphasised that they have never called for a complete ban on antibiotics for animals.

Campaigners say the industry is relying on antibiotics to counteract the impact of poor animal welfare, since animals are more likely to get sick and require antibiotics if they are stressed from being raised in tightly packed conditions, transported roughly, or made to endure practices like being debeaked or having their tails docked.

Ekaterina Solomina, a policy officer for animal welfare organisation Compassion in World Farming said that past and current use of antibiotics on farms enables practices that jeopardise animal welfare, including “high stock density, tail docking, [and] extreme breeding” – for example, breeding broiler chickens that grow much more quickly, or weaning piglets too early – because “antimicrobials can be used to maintain animals alive up to the point of slaughter.”

Other investments in animal welfare – including farming animals in less tightly packed conditions, giving them more access to outdoor space, and vaccinating them against disease – can reduce the need for antibiotic use while significantly improving animals’ quality of life, according to scientists and the WHO.

What the animal pharma industry says:

Opponents of stricter rules for animal antibiotic use often claim that restricting the list of approved medicines will mean that people won’t be able to treat infections in pets and other companion animals.

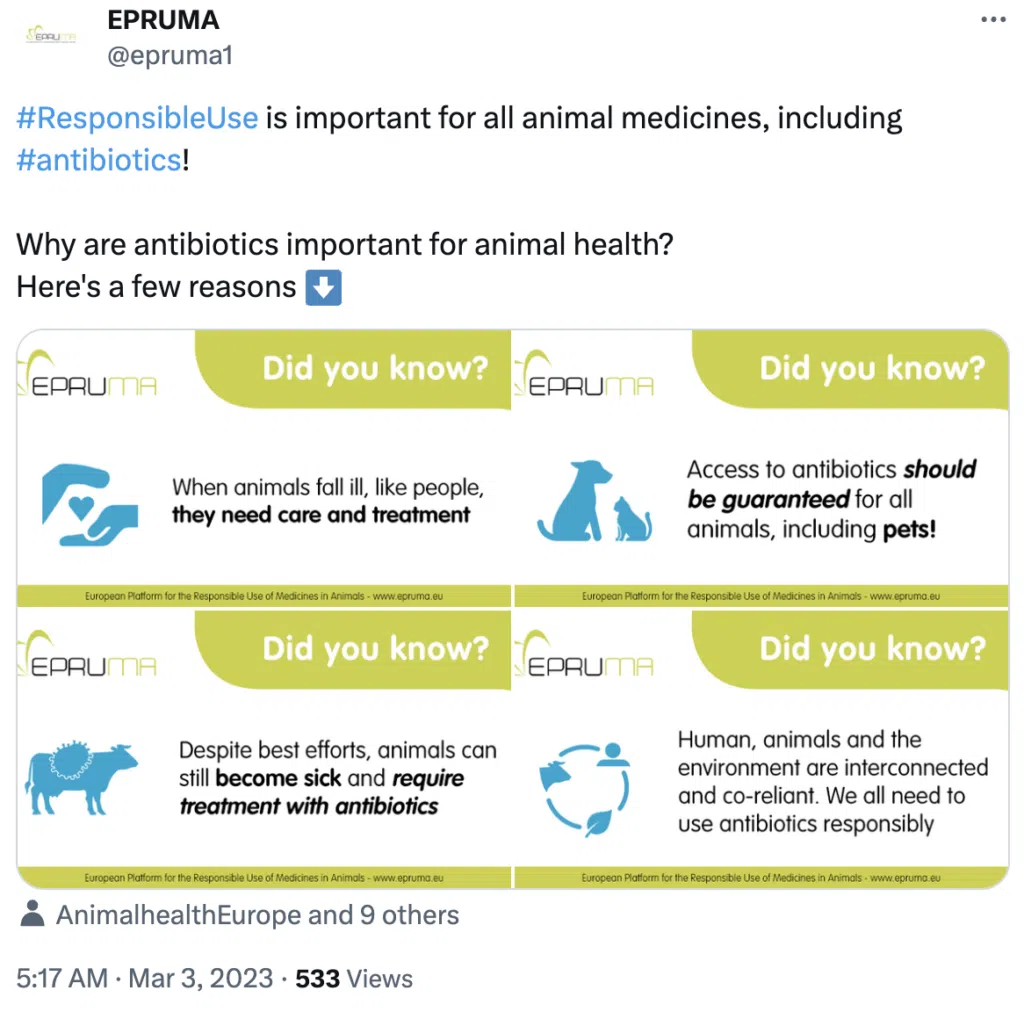

Industry body EPRUMA created infographics stating that “access to antibiotics should be guaranteed for all animals, including pets!”

Elanco has echoed this sentiment. In a document titled “Elanco Values Antibiotic Stewardship,” the company writes that if antibiotics were “banned or severely restricted, then veterinarians, farmers, and pet owners would lose the ability to protect animal health, mitigate suffering from disease, and prevent animal death.”

Concern about pets was a particularly prominent narrative cited by industry when the EU’s proposed list of human-only antibiotics was being considered.

In response to a 2022 proposal by MEP Martin Häusling to expand the list of human-only antibiotics, Nancy De Briyne, executive director of the Federation of Veterinarians of Europe, a trade association, said in an interview that the restrictions would leave vets with “nothing to treat” certain “multidrug-resistant” infections in companion animals or livestock.

The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe did not respond to a request for comment.

What campaigners say:

Inês Grenho Ajuda, a programme leader on farm animals with animal welfare group Eurogroup for Animals, said that the industry used pets to spearhead their argument that colistin – a “last resort” drug for infections in humans – could continue to be used on farms.

Colistin is used to treat digestive issues in piglets that are weaned from sows very early, a practice commonly used to allow sows to be inseminated again as soon as possible, Ajuda said.

While animal welfare organisations shared vets’ concerns that animals shouldn’t suffer from a lack of care because humans haven’t managed antibiotics correctly, they said the industry’s focus on pets was disingenuous.

“The industry campaigned, with vets being at the forefront, along the lines of, ‘your pet will not be able to be treated with antimicrobials,’ and [colistin] got left out [of the reserve list of human-only antibiotics],”Ajuda said.

Thomas Van Boeckel, a spatial epidemiologist at Swiss university ETH Zürich, told DeSmog that focusing on pets misses the bigger issue with antibiotic use in animals. “This is putting the focus on something that’s really not part of the debate. Because when public health people like myself argue for less antibiotics to be used, we talk about production animals, because the pets represent a tiny, tiny fraction [of overall antibiotic use].”

What the animal pharma industry says:

Animal pharma companies and lobby groups often say that their practices help increase food security.

Major pesticide and fertiliser companies deploy the same narrative, which cropped up often last year as concerns about food security grew after Russia’s invasion of major grain producer Ukraine.

New Jersey-based animal pharma giant Zoetis writes on its website that “healthy livestock, poultry, and fish are essential to a safe, sustainable food supply,” and that “responsible use of antibiotics in food-producing animals makes a difference in being able to meet the challenge of maintaining and increasing food safety and food security.”

This narrative is echoed by industry group AnimalhealthEurope, which writes that restricting antibiotic use would impact not only animal welfare, but would “have a substantial impact on Europe’s agri-food economy, at a time when other factors – including climate change – are affecting food production.”

What experts say:

Clapp, with the University of Waterloo, told DeSmog that the pharma and livestock industry’s food security argument “fail[s] to get to the heart of why people face hunger and food insecurity.”

She pointed out that over a third of the calories created by farming around the world feed livestock rather than people. Reducing demand by eating less meat, particularly in countries where it’s currently overconsumed, could yield the co-benefits of feeding more people while “reducing the environmental consequences of intensive livestock operations,” she added.

In recent years, intensive livestock farming has been increasingly scrutinised for its role in fueling the climate and biodiversity crises – both of which threaten global food security – due to its harsh impact on the environment, land and water pollution from farms, and greenhouse gas emissions.

What the animal pharma industry says:

The question of how antibiotic use in animals ultimately drives AMR in people – and to what degree – is one of the most contentious issues in the field.

DeSmog found that several actors in the animal pharma industry took pains to play up what they characterised as the “difficulty” of understanding how much and how often resistant bacteria makes its way from animals to humans.

For example, animal pharma lobby group EPRUMA has repeatedly argued in “myth busting” posts on its website that it is “impossible to estimate the extent of resistance transfer from animals” due to a lack of data about increasing colistin resistance in humans.

What experts say:

While the link between antibiotic use on farms and antimicrobial resistance in humans is still an active field of scientific research, many experts advocate for a precautionary approach.

Epidemiologist Thomas Van Boeckel said a “degree of truth” exists in saying that there is a lack of data linking antibiotic resistant infections in farm animals directly to infections in humans.

“It’s not easy to attribute an infection you have in your clinic to an animal,” he told DeSmog. “But an absence of proof is not a proof of absence. They are basically saying, don’t worry about it, because we don’t know enough. It’s a little bit like saying don’t worry about smoking in the sixties, because we don’t know enough. But a few years down the line, you realise we may have a serious problem.”

Colistin resistance is a good example of the risk AMR poses to human health. In 2015, colistin-resistant genes were identified for the first time in China, where the drug was being routinely used to treat livestock but had not yet been approved for use in humans. Despite that limitation, humans were being infected with colistin-resistant bacteria anyway – indicating that the bacteria were making the jump from animals to humans.

When it comes to colistin in particular, according to researchers at the University of Oxford, extensive use of the drug in livestock since the 1980s has “driven the spread” of E.coli bacteria carrying genes for colistin resistance.

In April, the researchers conducted a study to ascertain whether the commonplace use of colistin in agriculture could create a problem for humans: bacteria that was both resistant to the drug and could “overcome the human innate immune response.”

The study found that human and animal immune responses were not as effective against colistin-resistant bacteria, demonstrating that using colistin and other members of a class of drugs known as ‘antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)’ in agriculture can “generate broad cross-resistance to the human innate immune response.”

Professor Craig MacLean, who led the research, said that the widespread use of treatment options like colistin in agriculture will “lead to the evolution of AMP resistance” in bacteria that make humans and animals sick – eliminating a “promising alternative to antibiotics.”

What the animal pharma industry says:

The animal pharma industry often points to hospitals as the main risk factor for the spread of resistant bacteria.

According to Meat the Facts, a website created by animal agriculture lobby group European Livestock Voice, antibiotic use in animals is not as troubling as that in humans. The group points to a statistic from the European Centre for Disease Control stating that 75 percent of AMR-related infections stem from hospitals and other medical facilities. “Clearly,” European Livestock Voice writes, “even if we stopped all antibiotic use in animals, the impact on the human antimicrobial resistance problem would not be significant.”

EPRUMA has also downplayed the role of animal agriculture in driving AMR, writing in a “myth- busting” article that “banning certain antibiotics for use in animals will have little effect on the human antimicrobial resistance burden” because the “transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between species might happen occasionally and towards both directions.”

What experts say:

While the over- and misuse of antibiotics in human medical settings is the biggest factor driving AMR, reducing the overuse of antibiotics in livestock farming also has a role to play in curbing the threat.

Human health is a big reason to keep pursuing legislation that restricts the use of antibiotics in animals, according to Van Boeckel, who likened the constant use of antibiotics in livestock production to “playing the lottery.”

“You play the lottery three times more in animals than you do in humans, because they use three times more antibiotics. Now, that doesn’t mean that every nasty resistant gene that emerges in animals makes its way to [becoming] a human adapted pathogen,” he said. “But it can be seen as a very unnecessary risk, given how precious antibiotics are for humans.”

Despite a 2017 plea from the WHO calling on the food industry to stop using antibiotics on healthy animals, a 2019 investigation from The New York Times found that animal pharma company Elanco created a brochure that encouraged farmers to treat whole herds of pigs with antibiotics before a disease outbreak had ever occurred, to keep the animals from getting infected by a “patient zero” pig.

In response to the investigation, Elanco’s CEO Jeffrey Simmons told the Times that the company had stopped distributing the Pig Zero brochure, and that its content “wasn’t misrepresentation, necessarily, relative to the label or the science, or how a farmer would look at it.” Simmons added that Elanco officials “had a lot of dialogue about Pig Zero that probably we wouldn’t have had” without the Times’ investigation.

Dr. Shabbir Simjee, Elanco’s chief medical officer, said the antibiotics mentioned in the brochure “would never be administered” to a herd “without some animals being physically sick.”

Sarah Sorscher, deputy director of Regulatory Affairs at advocacy group Center for Science in the Public Interest, told the Times: “We’ve seen antibiotic-resistant bacteria that can leak into the environment through water and dust, jump to the skin of farmers, and swap genes with other bacteria.”

She added: “And that’s still just scratching the surface on the science. By the time we understand the full magnitude of this threat, it may be too late.”

What the animal pharma industry says:

Companies and industry groups communicated that if stricter regulations are passed, there may be an increase in both antimicrobial resistant bacteria and zoonotic diseases, which are caused when pathogens jump from animals into humans.

In its “myth busting” article, EPRUMA warned against any ban that would force the industry to depend on “only a few antibiotics” to treat animals, because it could “increase the selective pressure” on bacteria and “foster the selection for antibiotic resistant bacteria.”

HealthforAnimals also published communications that said “reducing antibiotic use without first tackling disease rates would mean sick animals go untreated, causing unnecessary suffering and mortality while increasing risk of transfer to other animals and people.”

Animal pharma giant Zoetis agreed, stating on its website that “healthy animals help reduce the risk of zoonotic infectious diseases that can pass between animals and people,” particularly those who raise and care for animals.

What experts say:

Van Boekel told DeSmog that while restricting antibiotics could theoretically increase the risk of zoonotic disease, that hasn’t played out in countries such as Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, where antibiotic use in food producing animals has dropped significantly in the last decade.

Antibiotics aren’t the only way to keep animals healthy: vaccines, improved hygiene, and better animal welfare help reduce the need for drugs, keeping them available and effective for sick animals that genuinely need them – helping to maintain their effectiveness.

“They [animal pharmaceutical companies] do see their treatment options eroding with time,” Van Boeckel said.

“If they have less treatment options, they won’t be able to treat the animal, and more generally, it reduces the ability of the industry to operate as it currently operates,” he said. “When it starts hitting their wallet, ultimately, that’s why I think they are also a bit more aware of it.”

What the animal pharma industry says:

DeSmog found that the industry likes to emphasise its successes in reducing antibiotic use, rather than focusing on the remaining work to be done to slow the growing threat of antibiotic resistance.

Elanco’s website emphasises the steps the company has already taken to reduce the use of antibiotics, stating that it has “intentionally shifted our business away from shared-class antibiotics” – those that are used to treat both humans and animals – “removed growth promotion from nearly 100 product labels globally” and “removed over-the-counter use from nearly 70 product labels to require the oversight of a veterinarian.”

Industry groups have also made this argument more broadly. Last year, AnimalhealthEurope wrote on its website that the industry had perhaps reached a level of “optimal” antibiotic use on European farms – implying the use of medicines had reached its lowest possible point – because antibiotic sales had dropped almost 47 percent on average between 2011 and 2021 before levelling out.

The latest numbers from the EU show that sales of antibiotics for farms fell by 12.7 percent from 2021 to 2022. Total sales have fallen 53 percent from 2011 to 2022 in 25 European countries. The EU’s ambitious Farm to Fork Strategy – a package of commitments designed to make farming in Europe more sustainable – aims to cut farm antibiotic use by 50 percent from 2018 levels by 2030.

European Livestock Voice wrote on its website in November 2022 that “We need to work together and stop blaming the livestock sector, which has made a lot of effort” to reduce antibiotic use in livestock.

What campaigners say:

Cóilín Nunan with Alliance to Save Our Antibiotics said that while the EU’s antibiotic legislation is radical on paper, it will have to be applied for humans and animals to reap the full benefits. “Not only do they ban all forms of routine use, but they also say that you may not use antibiotics to compensate for inadequate animal husbandry, poor hygiene or poor farm management practices,” he said. “If that were to be applied – and it is the law, so it should be applied – then that would mean changes to animal husbandry practices in the EU. But we’re not seeing that in most countries.”

Solomina with Compassion in World Farming said that while the EU does have an “advanced regulatory system” for the use of antimicrobials, it is not implemented robustly – meaning what’s actually happening on farms may not be falling in line with the goals of the legislation.

Solomina added that “many measures that are supposed to be implemented by [European] farms do not apply for the imported animal proteins,” leaving a major loophole in the EU’s approach to limiting the impact of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria on Europe’s animals and humans alike.

For Ajuda, with Eurogroup for Animals, the crowded, intensive nature of animal production that is currently reliant on antibiotics is what ultimately needs to change. “For us, use of antibiotics will be for cases where animals are in higher animal welfare systems and then still get sick, because all animals, even our companion animals, can get sick.”

“We would like to see systems that do not put pressure on the animal to the point that they’re stressed and their immune system is impacted,” she added.

If an animal gets sick when both prevention and higher animal welfare systems are in place, the group would support the correct use of antibiotics for a specific disease, advised by a vet.

What the animal pharma industry says:

The argument that veterinarians should be trusted to prescribe antimicrobial medicines to livestock was one of the industry’s most common narratives – and relies on the reputation of vets as champions of animal welfare.

New Jersey-based animal pharma company Phibro Animal Health takes this a step further. The company’s director of communication and consumer engagement, veterinarian Leah Dorman, writes about the role of vets in livestock farming on a blog called “Explore Animal Health.”

The company mentions the blog in its environmental impact reporting under the header “antibiotic stewardship.”

Dorman writes about how veterinarians “take an oath to protect animal health and promote human health,” and that “the use of antibiotics in agriculture is important to uphold both aspects of our oath.” She adds that “ending or decreasing animal suffering clearly helps to protect animal health, and healthy animals help ensure a healthy food supply for our families.”

What experts say:

While vets are indeed well-placed to monitor animal welfare and treat illnesses, they are not always involved in the prescription or supervision of antibiotic treatments. A shortage of vets for food animals – in the U.S., UK, Europe, Malaysia, South Africa and beyond – means that while vets may see animals initially, they may not be able to adequately supervise the use of antibiotics on farms.

Van Boeckel, of ETH Zürich, points out that in many countries, vets make money from antibiotic sales, so simply “trusting” them isn’t an effective way to ensure antibiotics are used sparingly. “Places like Denmark and Sweden,” where vets do not make a profit on selling antibiotics, “didn’t reduce antibiotic use through trust. They have quite aggressive policies with targets and a penalty system,” he said.

Solomina, of Compassion in World Farming, said there isn’t enough awareness from policymakers and the public regarding the “economic benefits” vets may derive from antimicrobial sales, and noted that “in some EU countries, veterinarians sell the antimicrobials directly to farms” – rather than medicine manufacturers selling to vets, who should then prescribe the medicines for animals.

The five industry associations included in DeSmog’s analysis were contacted for comment.

Roxane Feller, the AnimalhealthEurope secretary-general, told DeSmog in a statement that the animal health sector supports antibiotic stewardship and “responsible use of all medicines.” Feller emphasised that the industry has reduced antibiotic use by prioritising “preventative practices” including vaccination and nutrition, adding: “We are actively working with partners across the livestock value chain to reduce the need for antibiotic use for animal health purposes.”

“The animal health industry in Europe acknowledges its responsibility and remains firmly committed to playing an active role in addressing this One Health challenge of antibiotic resistance,” she said.

A spokesperson from EPRUMA said that all of its partners “support responsible use of all medicines and promote actions to reduce the need to use antibiotics for animal care.”

The EPRUMA spokesperson added that its partners “continue to work together on raising awareness on responsible use and reducing the need for antibiotics through a holistic approach that includes aspects such as good nutrition, enhanced biosecurity, good husbandry, preventive animal health plans and vaccination.”

A spokesperson for HealthforAnimals – which also responded on behalf of its members Zoetis, Elanco, and Phibro – told DeSmog that the sector “supports responsible use and reducing the need for antibiotics.”

The spokesperson added: “A preventative approach recognizes that tackling underlying disease is the only way to reduce antibiotic need in a manner that respects animal welfare and protects public health. More work will be done in the years ahead to continue tackling animal disease and reducing antibiotic need and we encourage others to learn from the successes achieved in animal health.”

The Federation of Veterinarians of Europe and European Livestock Voice did not respond to requests for comment.

This story originally appeared in DeSmog.