Explainer

Agriculture Affects Deforestation Much More Than Most People Realize

Climate•7 min read

Explainer

Cutting food waste is a huge potential climate win. Why are we ignoring it?

Words by Gaea Cabico

This story is a partnership between Floodlight and Sentient, with visual reporting by Floodlight’s Evan Simon. Sign up for Floodlight’s newsletter here.

In the United States, climate change is polarizing, but one environmental challenge draws rare bipartisan agreement: food waste. Even as the Trump administration rolls back key climate and environmental protections, in July, senators from both parties reintroduced legislation to simplify food expiration labels — one longtime driver of unnecessary waste. In September, the Environmental Protection Agency launched a national initiative to connect food donors with communities and keep edible food out of landfills. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. unveiled a national strategy to reduce food waste and expand recycling of organic waste.

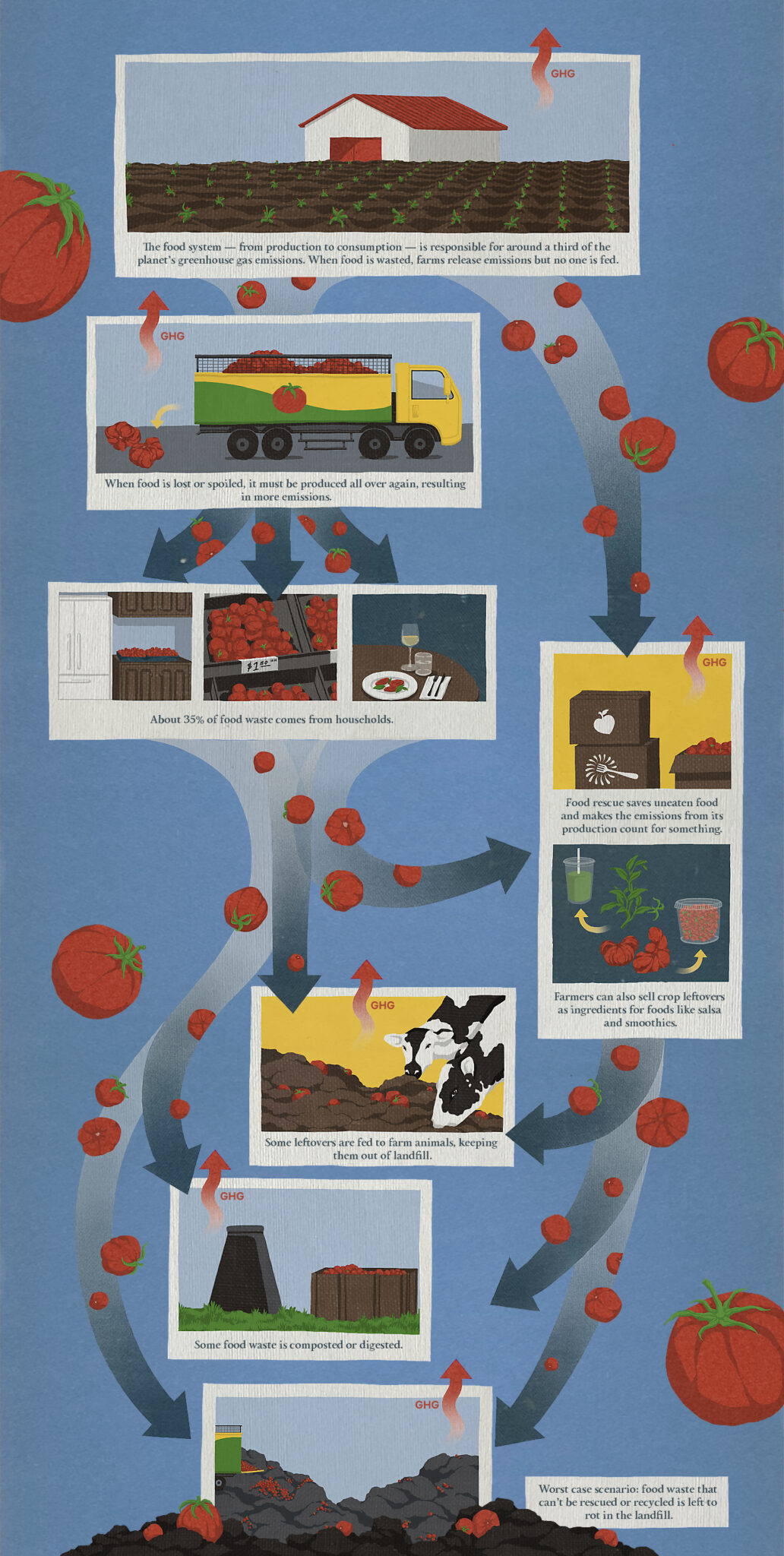

Despite this rare consensus, progress has been slow. In 2023, the U.S. still squandered roughly a third of its food supply, according to the food waste nonprofit ReFED. Food waste is responsible for 8-10% of all global emissions — about five times the emissions from the entire aviation industry. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that if food waste were a country, it would be the world’s third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China and the U.S.

Experts tell Sentient that the problem persists because political follow-through is limited, climate action still focuses heavily on energy and transportation and ultimately, food waste itself is difficult to tackle. It occurs at every stage of the supply chain, from farms to fridges, making comprehensive action essential.

It’s also a missed opportunity, especially since wasting food is widely seen as wrong. “Nobody wakes up wanting to waste food,” said Dana Gunders, president of ReFED, during a summit at New York City Climate Week on September 22.

Many people don’t realize that food waste reduction is a crucial and often overlooked climate strategy. Addressing food loss and waste has enormous climate potential, “but it’s still an underexplored area,” says Brian Lipinski, head researcher on food loss and waste at the environmental research non-profit World Resources Institute.

Most food waste happens in homes, restaurants and retailers, but nearly all of its climate impact is already baked in by the time the food is thrown away. Every piece of wasted food squanders all the emissions that went into producing and transporting that food. About 92% of food waste emissions happen during food production — when land is converted from forests or grassland to farmland, when resources are used to grow crops or raise livestock, during transport in which most vehicles run on diesel or gasoline, and during cold storage. Once that food is tossed, those emissions are wasted. Only 8% of food waste emissions come from the disposal process.

When people are wasting food, “in many ways, we are throwing out a lot of water, a lot of land, a lot of fertilizer, natural habitat, a lot of things,” Paul West, a senior scientist at the climate nonprofit Project Drawdown, tells Sentient.

Fruits and vegetables make up almost half — 44% — of all U.S. food waste, according to ReFED. Meat and seafood, though also quick to spoil, are wasted less often because they are more expensive.

But wasting even a small portion of a burger has far greater environmental impact than wasting the same amount of fruits, vegetables or chicken, says West. That’s because producing beef requires vast amounts of land, water and fertilizer, and cattle also release methane — a short-lived but powerful greenhouse gas — with each cow burping about 220 pounds annually. “If we are going to eat beef and dairy, make sure not to waste it,” says West.

Experts see reducing food loss and waste as one of the most impactful and practical ways to slow the warming of the planet. Project Drawdown calls it an “emergency brake” solution — a measure that can rapidly slash emissions using tools we already have, without waiting for new technologies or nature-based fixes. Other such measures include halting deforestation and shifting away from meat and dairy.

“Preventing food from becoming waste is really the most effective solution, not only from an emissions perspective,” says Minerva Ringland, senior manager of the climate and insights team at ReFED, “but it’s also saving the most money and keeping everyone fed as much as possible.”

In the United States, 35% of food waste comes from households, while 18% comes from manufacturing and 17% from food service, and 24% happens on farms. Household waste is high because people often buy more than what they need, especially in bulk, misinterpret date labels, prepare too much food and may not know how to store or repurpose ingredients. Limited access to composting programs also makes it harder for consumers to avoid landfills.

Experts suggest households can curb waste by planning meals, buying only what’s needed, using smaller portions and repurposing leftovers. Emily Broad Leib, director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, says the U.S. needs a national consumer awareness campaign, similar to the United Kingdom’s Love Food, Hate Waste campaign. She notes that the Biden administration set aside funding to develop such a campaign, but it has since stalled. Many people don’t realize how significant the issue of food waste is, she says — not just for the environment but for their own finances.

But reducing food waste at home is not just about telling people to be more careful or intentional about their purchases. After all, food waste is rarely intentional. Maybe you buy an ingredient for one recipe and never use the rest, or forget the leftovers in your fridge and they go bad. Lipinski says that retailers and food service providers can help consumers avoid waste by offering smaller portions, clearer guidance and smarter packaging.

Government agencies can lead by example in reducing food waste in their dining halls, federal buildings, schools and military bases by requiring vendors to donate surplus food, Broad Leib suggests.

These strategies are worth the effort because preventing food waste at its source offers climate benefits about 10 times higher than other strategies since it reduces the need for producing additional food.

Beyond prevention, the EPA identifies donation and upcycling — turning food into new products — as the most preferred approaches. However, 40% of donated food still goes to waste and both strategies require energy for transport, storage and processing. According to the EPA, using wasted food as animal feed, leaving crops unharvested, composting and anaerobic digestion do much less to offset the environmental impacts of food production than preventing food waste in the first place.

Most of the country’s surplus food still ends up in landfills, compost facilities, incinerators or anaerobic digesters, according to ReFED. Only about 2% is donated. Food makes up about nearly a quarter of combusted municipal solid waste that ends up in landfills.

In landfills, food waste decays and releases methane, a gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat over a 20-year period. Landfills produce 17% of human-related methane emissions in the U.S., after oil and gas and livestock digestion. A majority of the methane released from landfills in the U.S. comes from food waste, according to the EPA. A separate analysis by ReFED estimates that surplus food generates nearly 3 million metric tons of methane each year.

Improving landfill management is one of Project Drawdown’s highly recommended climate solutions. To capture or reduce methane emissions, some landfills install systems that divert landfill gas so that it can be burned for energy and sold to industries or utilities, helping replace fossil fuels. Methane that cannot be used for energy is typically burned off using flares. Another approach uses biocovers — layers of organic material that foster bacteria that convert methane into carbon dioxide and water. Leak detection and repair programs can monitor methane leaks using drones, satellites or on-site sensors, which helps operators spot and fix leaks.

Encouraging composting instead of putting food scraps in landfills also helps. But West says that while composting and landfill management matter, “you’ll have many times more impact if you stop the waste in the first place.”

For something so uncontroversial, food waste has proven remarkably hard to fix.

In 2015, the U.S. set an ambitious goal of halving food loss and waste by 2030 — a target experts say is quickly becoming out of reach. No state is on track to meet the target, researchers from ReFED and University of California Davis found in an analysis published in January. They warned that food waste levels are unlikely to fall without stronger state and federal action focused on prevention measures such as standardized date labeling, food rescue and repurposing. Current policies, they noted, focus too narrowly on recycling methods like composting rather than addressing the problem across the entire food system.

Standardized date labeling is one of the most cost-effective fixes, ReFED argues. In the U.S., 6% of all food waste is due to confusion over date labels. Many U.S. consumers don’t know the specifics, but there is no national standard for date labels. Some products have “Sell By” dates, others have “Best Before” dates, and still others have “Use By” dates—and they often mean different things in different states. The dates on packaging are “not designed for consumers to understand clearly,” Ringland says.

As a result, many people toss food after the printed date, assuming it is unsafe to eat. This confusion leads Americans to discard about 3 billion pounds of perfectly fine food worth $7 billion each year. “Sell buy,” “best before,” and “use by” dates usually indicate how long a product will stay at peak quality, not whether it is still safe to eat. According to the USDA, the “Best if Used By” or “Best Before” date shows when the product will taste or look its best. “Sell By” indicates how long a store should keep a product on the shelf, and is meant for communication between manufacturers and retailers, but is often mistaken by consumers for an expiration date.“Use By” is the last date the product is at its best quality.

If you have a can of beans in your cupboard with a “Sell By,” “Use By,” or “Best Before” date, it does not necessarily mean you should throw it once that date passes. ReFED says that many foods such as canned goods, nuts and dry packaged goods can remain edible past the printed date.

To address this, ReFED advocates for a two-label system: “Best If Used By” and “Use By.” “Best If Used By” indicates product quality: it may not taste its best, but it is still safe to consume. This label is recommended for use for canned goods, bread, raw meats, frozen foods and pasteurized products. Meanwhile, “Use By” would apply to highly perishable items or those that pose a risk to safety over time like deli meats, unpasteurized milk and soft cheeses, and smoked seafood. These products should be eaten by the date on the package and tossed afterward. If passed, the bill reintroduced in the Senate would make that standard nationwide. Similar measures have been introduced in the past but have not advanced. ReFED estimates that standardizing labels could keep at least 425,000 tons of food — or 708 million meals — out of landfills each year.

“Even though the issue is something that both Republican and Democratic administrations have cared about and worked on, there’s a lot of momentum that gets lost in between administrations,” Broad Leib says. The lack of sustained policies, she adds, has prevented the U.S. from making meaningful progress in reducing food waste.

Still, there are signs of progress, especially at the state level. That’s probably where we’ll see more momentum under the Trump administration, says Lipinski.

In 2024, California signed the country’s first legislation to adopt a clear two-label system on food products. Starting July 1, 2026, the law will also ban the use of “sell by” dates.

Another is the implementation of state-level mandates that prohibit sending commercial food waste to landfills. States including California, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont and Massachusetts have enacted such bans. However, a study published last year found these policies have largely fallen short — except in Massachusetts, which succeeded in reducing the amount of food waste sent to landfills by 13%. Researchers found that Massachusetts has the country’s most extensive food waste composting network, making it easy and low-cost for businesses and households to follow the ban. The state’s rules are straightforward, with no exemptions, and authorities conduct far more inspections and issue more fines for violations than in other states. These differences point the way toward better implementation in other states.

Experts say that stronger incentives for grocers and restaurants to donate food could also make a significant difference. Some states like California now require some commercial establishments to donate edible food that they would otherwise throw out.

“We’re seeing pockets of progress everywhere,” says Ringland. Because food waste is a complex problem, she adds, “We’re going to need a lot of solutions.” The key is turning these scattered successes into coordinated and sustained action across the supply chain, which can save money, slash emissions and put food on tables.