News

Minnesota Asks the Public Whether Groundwater Rule Is Enough to Curb Farm Fertilizer Pollution, Following Lawsuit

Climate•7 min read

Analysis

New wildlife report reveals 49 percent of bird species are decreasing.

Words by John C. Cannon

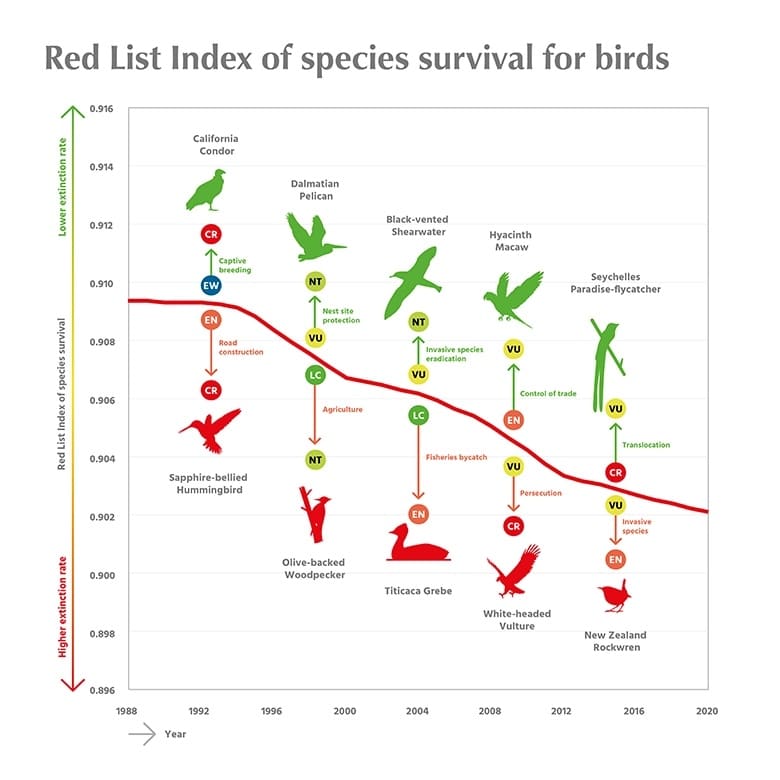

The world is losing species alarmingly fast. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), an independent science and policy group, says a million species face extinction. Few animals bring these unsettling losses into sharper focus than birds: Populations of 49% of avian species are decreasing, according to a September 2022 report by the conservation partnership BirdLife International.

In December, world leaders, policymakers and scientists will gather at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal to agree on a plan that will address the causes of the global loss of species by 2030. A key aspect of the negotiations is the quest to protect 30% of Earth’s land and water by the end of the decade, a move that many biologists say could improve the outlook for birds, other wildlife and plants if countries sign on and prioritize meaningful conservation measures.

“This is a once-in-a-decade opportunity to really ratchet up the magnitude of response that governments are putting in place to address this crisis,” Stuart Butchart, chief scientist with BirdLife International, told Mongabay. Butchart was a senior editor of the group’s “State of the World’s Birds” report released in September and a co-author of a related study published in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources May 4.

BirdLife International issues assessments of the status of birds every four years.

“Between reports, we see many of the most important threats coming up over and over again,” said Lucy Haskell, science officer at BirdLife International and the report’s lead author. Haskell was also a co-author of the May study.

The latest report, drawing from dozens of studies, confirms that the threats to bird survival are intensifying and the number of affected species is growing. In 2018, 40% of bird species populations were estimated to be decreasing, compared to nearly half today.

Globally, habitat loss, mostly from agriculture, is the greatest threat to birdlife. Hunting, bycatch in fisheries and contact with energy infrastructure also pose major problems for birds. And invasive species can be devastating to birds, especially on islands.

More recently, avian flu has begun to take a larger toll on a wider variety of species. The influence of climate change is also growing, sparking sea-level rise, drought and wildfire. It’s also shifting bird ranges, often to cooler climes at higher altitudes or nearer to the poles, in what ornithologists call an “escalator to extinction,” Haskell said. At least two climate-related issues would affect 97% of bird species in the United States by 2100 if global temperatures were to rise by 3° Celsius (5.4° Fahrenheit) over pre-industrial levels.

“It’s incredibly worrying that these impacts are going to multiply and intensify as global warming continues,” Haskell said.

What’s more, the effects on birds provide a snapshot of what humans and other animals may experience. Scientists look to birds as indicators of what the future may hold because they live in many parts of the world, are relatively easy to study and respond to their environments.

“Birds are canaries in the coal mine,” Amanda Rodewald, a professor of natural resources and the environment at Cornell University in the U.S., who was not involved in the report, said in an email.

Research suggests that using what we know about birds and how to encourage their survival will likely help other species. Those actions aimed at bird conservation are likely to benefit humans as well.

“The question is not ‘do we take care of birds, or do we take care of people?’ but rather, ‘how do we serve both?’” said Rodewald, also the senior director of the Center for Avian Population Studies at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. “If the environment isn’t healthy for birds, it’s unlikely to be healthy for us.”

Declines in bird populations are evidence of humans’ “broken relationship” with the natural world and the role it played in setting up the COVID-19 pandemic, Haskell said. “It shows how our overexploitation of wild animals and the destruction and degradation of their habitats is increasing that risk of diseases being transferred from wild animals to humans.”

Research over the past four years has deepened the understanding of links between birds and human health, according to the report.

“Lots of people really turned to nature during the pandemic as a … form of comfort and solace in those really difficult times,” she said.

Indeed, scientists recently identified a correlation between the presence of birds with a lower prevalence of depression. Another study connected higher numbers of bird species living nearby with greater reported satisfaction in life.

The trends that many species face are worrisome, Haskell said, but birds have shown the ability to recover — if they’re given the chance. Since 1993, conservation has helped save 21 to 32 bird species from extinction, according to research cited in the report. Losing those species would have doubled or tripled the extinction rate over that period.

The ability to pull species back from the brink “is a good illustration of what can be achieved,” said Butchart, a co-author of that 2020 study.

“Everyone’s heard of the dodo, and everyone comprehends extinction and its finality,” he said. Humans are not as good at stopping the slide before the situation becomes dire, and doing something about it would be “much more cost-effective,” he added.

The challenge now is to take on the more difficult task of changing a global system of trade and consumption that’s driving the loss of biodiversity, Butchart said.

The tools to stem the crisis are available, Haskell said, even with the “depressing news from the report. “We do know what to do about it.”

Habitat loss, mostly for agriculture, remains the most significant threat to birds and to biodiversity in general. The consumption of food crops like soybeans, which have replaced forests in parts of the Amazon, is responsible for one-third of the impacts on biodiversity in Central and South America, the authors write.

The report also notes that more than 28% of “key biodiversity areas,” which include intact ecosystems and repositories of animal, plant and fungi species, overlap with land managed by Indigenous peoples. Globally, these areas hold 80% of all biodiversity and at least 36% of remaining intact forests. Deforestation, which destroys the habitat of many forest-dependent bird species, is also two to three times lower in these places.

But half of the Indigenous-held lands that hold key biodiversity areas aren’t yet protected. By protecting these lands, governments could benefit both species conservation and the people who care for them.

The question of how best to protect lands for both people and biodiversity will be a major issue at the U.N. Biodiversity Conference beginning Dec. 7. Haskell called it “probably our best and perhaps one of the last chances” to scale up conservation measures to halt species loss.

Butchart called the conference a “pivotal moment” for countries to put the necessary conservation measures into practice.

“This isn’t just about keeping some pretty birds and animals alive for us to enjoy,” he added. “This is really existential and comes back to impact our own health and economies.”

Additional reporting by Liz Kimbrough.