Feature

Southern Right Whales Are Having Fewer Calves. Scientists Say a Warming Ocean Is to Blame.

Climate•6 min read

Analysis

Livestock is a major contributor to climate change. But in the scientific community, there's a surprising lack of consensus around just how much livestock production is adding to the problem. Environmental researcher Nicholas Carter makes the case for a new approach.

Words by Nicholas Carter

The production of animal-based instead of plant-based foods has become a significant reason for climate change, yet fewer than 10 percent of United States college respondents associate eating animals as a significant contributor. Animal agriculture is responsible for a significant share of damage caused by land degradation, air pollution, water shortage, water pollution, and to the loss of biodiversity. The discrepancy in the communication on this industry’s global environmental impact ranges widely.

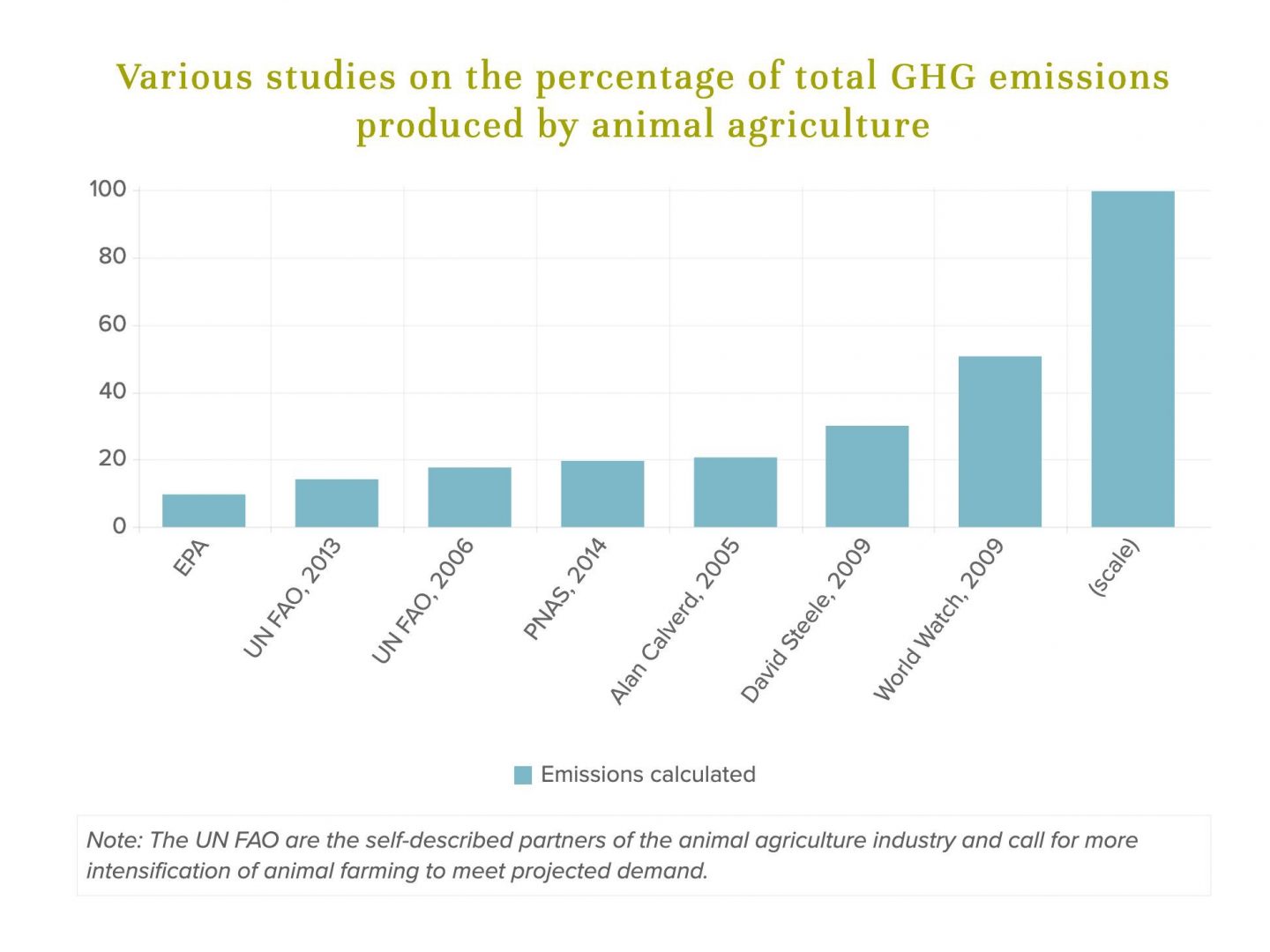

Research on animal agriculture’s share of anthropogenic global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions varies from 14.5-51 percent.

The inconsistency between the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) figure of 14.5 percent and the Worldwatch Institute’s figure of at least 51 percent will be explored below based on this research.

There is a global need to find ways to reduce our ecological footprint, live sustainably, and live within our planetary boundaries. What is communicated on what contributes to the most global anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions should be dependent on the manufacturing methods of various products, but it seems to be communicated based upon various research methods used. The media’s focus has been on industrial and transportation fossil fuel use as main culprits for this contribution. However, animal agriculture, which now includes over one trillion aquatic animals and over 82 billion land animals raised and slaughtered yearly for human consumption, is a significant burden ecologically and offers a major opportunity for immediate reductions in emissions.

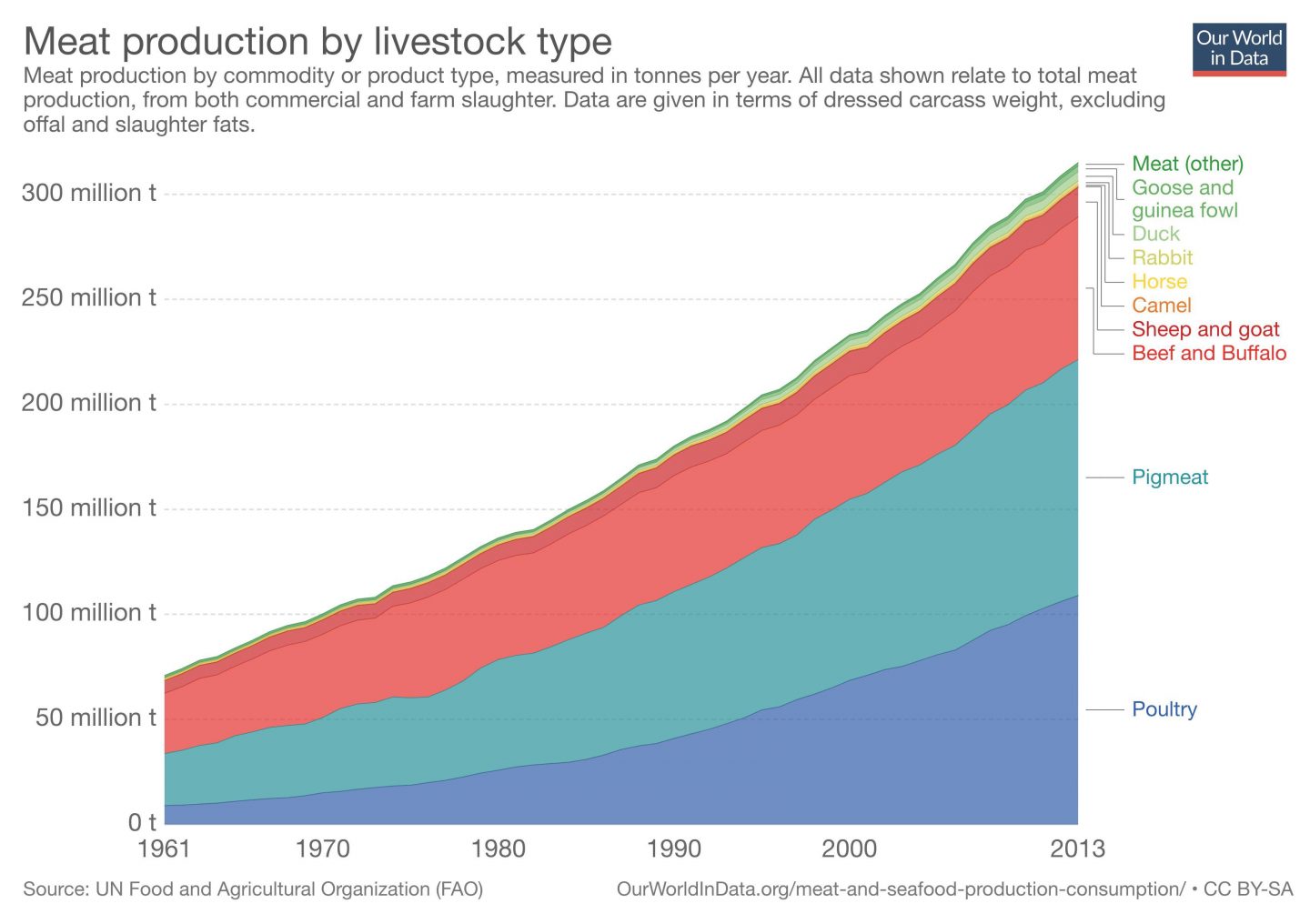

One scenario shows this burden will worsen as livestock inventories are predicted to double by 2050. Another scenario though shows it could be halved by 2030, enforced by the effects of climate change, awareness on the environmental impacts, and through instructed systemic change.

While many researchers in this field agree that animal agriculture is a contributor to climate change, there is disagreement on the global estimated percentage of and the strategies for reducing this environmental degradation.

In 2006, the FAO stated:

“There is a very substantial contribution of animal agriculture to climate change and air pollution, to land, soil and water degradation, and to the reduction of biodiversity.”

The 2006 FAO report goes on to state that “if, as predicted, the production of meat will double from now to 2050, we need to halve impacts per unit of output to achieve a mere status quo in overall impact.” Overall, the FAO report stated that animal agriculture is responsible for 18 percent of anthropogenic GHG emissions globally (7,516 million metric tons per year of CO2 equivalents).

Based on calculations from the 2013 FAO report, called Tackling Climate Change through Livestock, animal agriculture contribution to GHG emissions dropped to 14.5 percent of total GHG emissions (in CO2 equivalent). Both of these extensive FAO reports were not conducted by environmental assessment specialists, but instead by livestock specialists with an inherent bias to improve this sector internally, instead of looking at plant-based alternatives for feeding the world. Some appreciate these FAO percentages to be valuable as baseline statistics, but there are many issues with these reports, including that they do not count the majority of GHG emissions attributed to livestock.

According to the 2013 FAO report, changes in soil and vegetation carbon stocks not involving land-use change can be significant but are not included.

If one were to count all soil carbon emissions worldwide from feed production and the degradation of pasture due to grazing, the aggregate of such GHG emissions would likely exceed all GHG emissions presently attributed by the FAO to livestock. An improved unbiased analysis of animal agriculture’s land use, crop use, deforestation, and freshwater use is required.

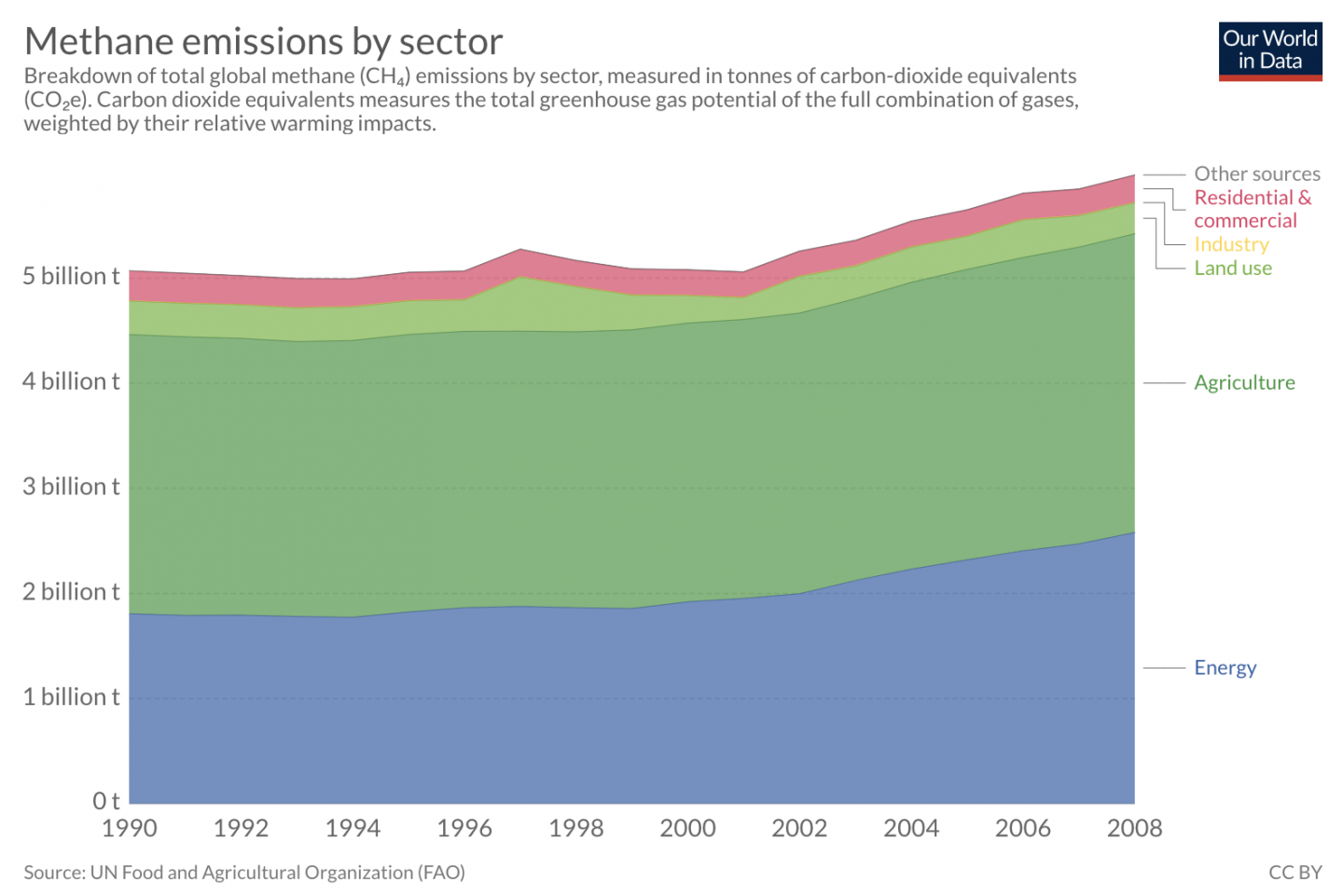

A significant disagreement between the 2009 Worldwatch report and the 2006 FAO report, and even the later FAO report, updated in 2013, is the calculation of the global warming potential (GWP) of methane. Both UN FAO livestock specialist reports used a GWP of 23 for methane over a 100-year time horizon. However, research published in Global Change Biology states that the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has supported the use of a GWP of 72 for methane over a 20-year timeframe concerning livestock-related methane emissions.

The fifth assessment report from the IPCC, published in 2014, supports an even higher GWP of 86 for methane over a 20-year timeframe. However, for comparison purposes, using the lower GWP of 72, the contribution of animal agriculture increases to 7,416 million tons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) or 11.6 percent of worldwide anthropogenic GHG emissions. This 20-year timeframe, instead of 100, is needed because of the growing urgency of climate change. Critics of this change will explain that methane has a shorter half-life than CO2. Worth noting though is that methane warms the planet at 72-86 times the rate of CO2 over a decade or two, before itself decaying into CO2. A continuous stream of methane emissions, like those from livestock, will ensure that old methane is just replaced by new methane.

With this better measure, GHG emissions attributable to livestock products increased by 5,047 million tons of CO2e, or 7.9 percent, according to the Worldwatch report. Research from a group of Canadian climate scientists supports this 20-year time frame, as well in their study that compared methane emissions from various types of animal protein sources. Keeping the time horizon at 100 years versus 20 years decreases the value of methane by about 2.5 times.

The leading scientists behind the 2018 IPCC report warned that we have a mere 12 years to keep global temperatures under 1.5 degrees Celsius, beyond which only half a degree more will dramatically increase chances of flooding, drought, and extreme heat. It is crucial to get these timeframes and calculations correct to ensure the focus is on addressing the biggest contributors to climate change accurately.

To begin to adjust the contribution of animal agriculture to anthropogenic global GHG emissions, the Worldwatch report used the FAO’s calculation that 37 percent of all methane comes from livestock and then increased the total GHG emissions from there. It is worth noting that 50-75 percent of increased methane emission from 2003-2010 is due entirely to livestock. Methane, at rates shown by the IPCC, is expected to cause 15-17 percent of the global warming over the next 50 years, according to a report published in the Journal of Animal Science and cited in the IPCC’s 2014 report.

If addressing methane rightfully becomes a more significant focus, then consider that cattle account for 73 percent of the livestock’s global methane emissions. Cattle in Canada are responsible for 88 percent of the total livestock methane emissions.

Neither the 2006 FAO report nor the 2013 update include respiration (carbon dioxide) as a GHG emission source. They claim that the photosynthesis perfectly offsets this livestock respiration. If it were only a few million animals raised for food, then that would be accurate, however globally there are 82 billion land-based livestock raised for food, and the amount of respiration has increased significantly. Physicist Alan Calverd, when trying to radically address the Kyoto Protocol, found that livestock respiration alone accounted for 21 percent of anthropogenic GHG emissions worldwide (about 8,769 million tons).

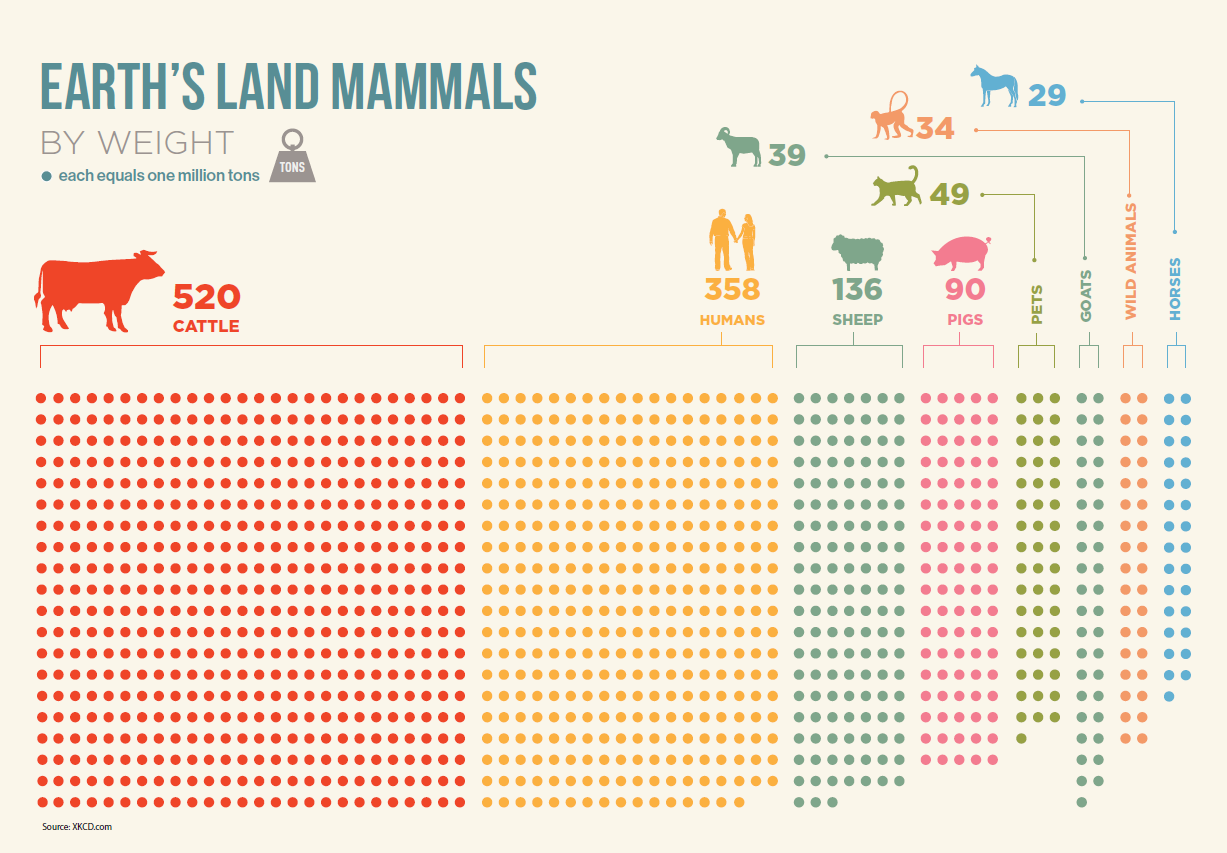

The massive amount of livestock has “caused a dramatic decline in the Earth’s photosynthetic capacity, along with large and accelerating increases in soil carbon volatilization.” Livestock, who are the main drivers of soil oxidation, have a mass about eight times that of wild animals.

If respiration and soil oxidation are more than the photosynthesis capabilities, then counting respiration emissions seems very necessary.

The 2010 FAO report’s recommendations for addressing climate change through animal agriculture involve selective choices of feed crops and more intensive factory farming. According to the report, more success will come from changing production style and increasing industrial farming in third world countries. There is no mention any results will come from a policy that focuses on educating people about more healthy plant-based options of eating. Based on the authors’ work as livestock specialists, the report goes on to state that supplies of meat and dairy can be met without a systemic shift away from animal farming, but instead with better management of land, more intensification of farming, and more deforestation to meet feed crop requirements. If the focus is on simply improving the livestock sector, silvopasture or regenerative agriculture could have been examples suggested to improve the livestock sector.

Alternatively, the 2009 Worldwatch report indicates animal agriculture accounts for at least 51 percent of total human-induced GHG emissions in CO2 equivalent (32,564 million tons). The major culprits for this increase from the UN FAO reports are that the Worldwatch report factors in livestock respiration (CO2), undercounted methane, and overlooked land use. The report reviews both direct and indirect sources of GHG emissions from animal agriculture using a full life cycle assessment.

Unlike the FAO reports, the Worldwatch report followed the GHG protocol and included what is considered Scope 3 emissions. Scope 3 includes the many parts of the supply chain not owned by producers. Some other factors they used to determine the 51 percent are underestimated figures, while others are overlooked or already counted for but assigned to different sectors (i.e., deforestation for feed crops). The FAO reports also used outdated models of the carbon cycle and allocated categories like deforestation to other sectors, according to Paul Hawken, author of the New York Times bestselling book Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever to Reverse Global Warming (Penguin Books 2017).

Overall, the Worldwatch report suggests that the UN reports failed to develop a true whole life cycle assessment (LCA) of anthropogenic GHG emissions attributed to livestock. It concludes that promoting plant-based options should be a major focus for addressing climate change and biodiversity issues.

The 2013 FAO report only included the change in land use and deforestation over time from animal agriculture, which is relatively small, compared to the Worldwatch report, which includes the huge amount of land already in use for livestock production. The Worldwatch report also includes the deforestation factor related to livestock and livestock feed. There’s much debate on these points, which still require further comparison and research.

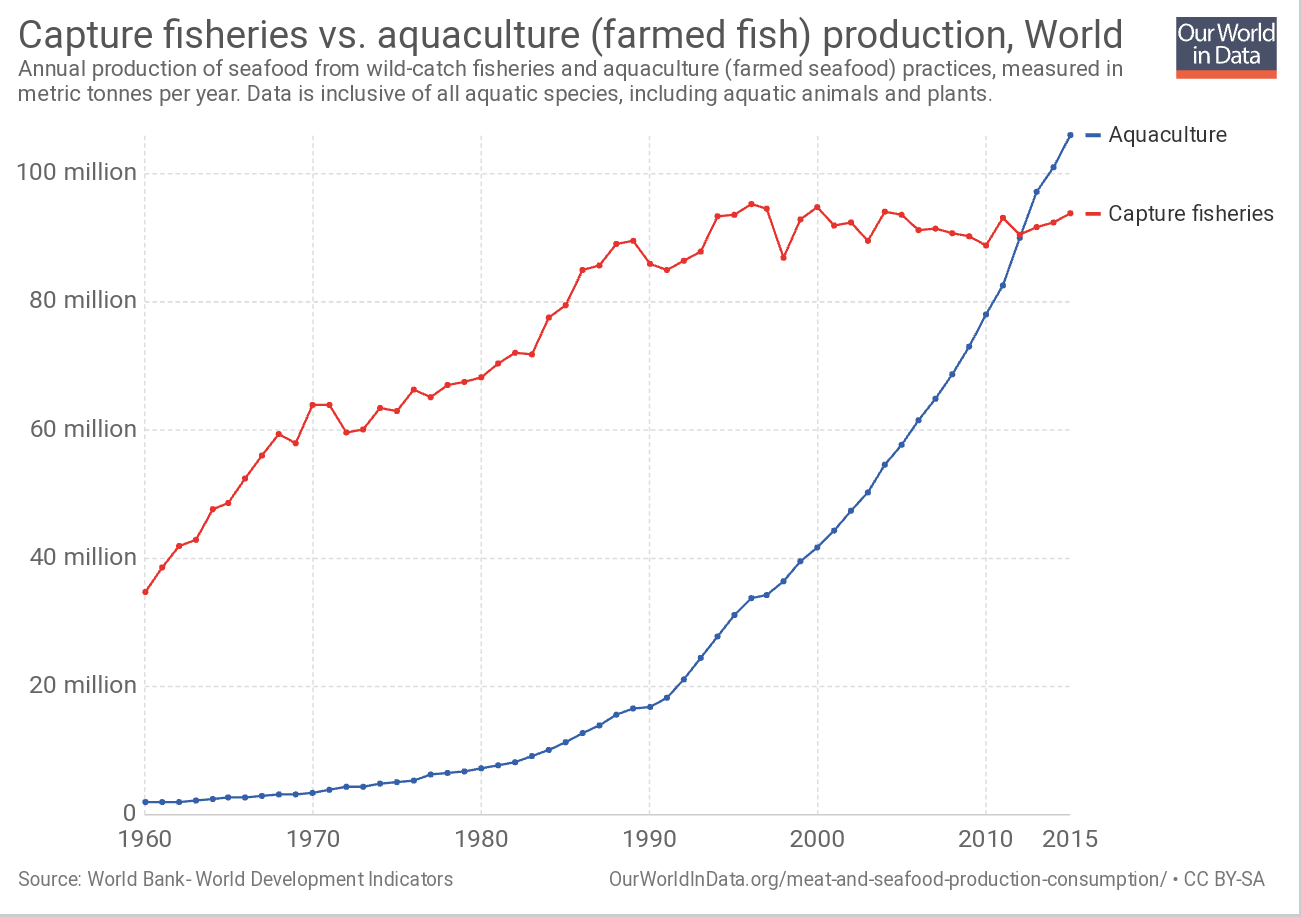

Additionally, the 2006 and 2013 FAO reports fail to include an entire category that is increasingly detrimental to the environment. They excluded all aquatic animals farmed for human consumption and livestock feed. Fish farms, for example, can generate significant coastal pollution in the form of excess feed and manure. Escaped fish and disease from these farms can completely deplete wild fisheries.

A 2008 Worldwatch Institute article found the following:

A fish farm with 200,000 salmon releases nutrients and fecal matter roughly equivalent to the raw sewage generated by 20,000-60,000 people. Scotland’s salmon aquaculture industry is estimated to produce the same amount of nitrogen waste as the untreated sewage of 3.2 million people – just over half the country’s population.

Land-based fish farming is not any better. This method has shown to produce significant ecological changes downstream, reducing biodiversity and killing pollution-sensitive species. Overall, fish farming is an inefficient way to feed the world. To raise one pound of salmon, you need over two pounds of wild fish to produce its feed. It is estimated that aquaculture and fish farming is already producing nearly half of humans’ entire seafood consumption, yet there is a lack of standards for what is “good” fish farming and how it can be done sustainably. All this said, the damage caused by animal agriculture needs to include fishing.

The FAO conclusions lack insight into groundbreaking innovations and alternatives to animal farming. The 2006 FAO report even stated, “the principal means of limiting livestock’s impact on the environment must be… intensification.”

FAO’s conclusion that animal agriculture’s contribution to anthropogenic global GHG emissions of 14.5 percent is significantly too low. Even if one wants to use the outdated carbon cycle calculations of methane’s GWP or exclude the vast amounts of land use for feed or grazing, that percentage is still too low. There needs to be more research on the respiration of animals and if it has caused a decline in the earth’s photosynthetic capacity and is therefore no longer offset by previous carbon sequestration. More research like this that looks at various examples, instead of making generalizations, is also needed on the recent increases in volatilization in soil carbon based on common animal grazing methods.

A recent analysis published in Science showed that 83 percent of all farmland is used for animal agriculture.

The inclusion of carbon-storing benefits of land better purposed, for example, re-forested, would shift total anthropogenic GHG emissions attributed to animal agriculture well above the FAO’s 14.5 percent. A 2018 report published in Science, “Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers,” concluded that the personal contribution to this 14.5 percent would effectively be eliminated on a vegan diet.

Factoring in changes in land use for increased carbon storage on a vegan diet would reduce one’s total personal GHG emissions by 30-50 percent.

A critique of the Worldwatch report makes the point that transportation does not get a full life cycle analysis and so cannot be compared apples-to-apples with the livestock industry. However, as the authors of the Worldwatch report allude to in this response article, the reason why transportation and energy sectors lack full life cycle analyses can be explained.

The most widely-accepted protocol for counting GHG emissions, the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, mandates counting emissions from both direct and indirect sources (other industries), which can result in double-counting. However, the transportation and energy sectors were not done in this way because the guidance and standards set by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol outline that items should only be double-counted when something can be realistically done to reduce them.

Immediate overhaul of the livestock industry through production and consumption can have immediate benefits by looking at the direct and indirect emissions while the same cannot be said about the transportation industry’s indirect emissions. As will be shown, immediate replacement of animal- to plant-based alternative foods can be done relatively quickly, and this is a unique solution for this industry. This transition can be done through a voluntary decision from the consumer to choose plant-based options, or if it becomes pressured from industry and government as a manner to address climate change.

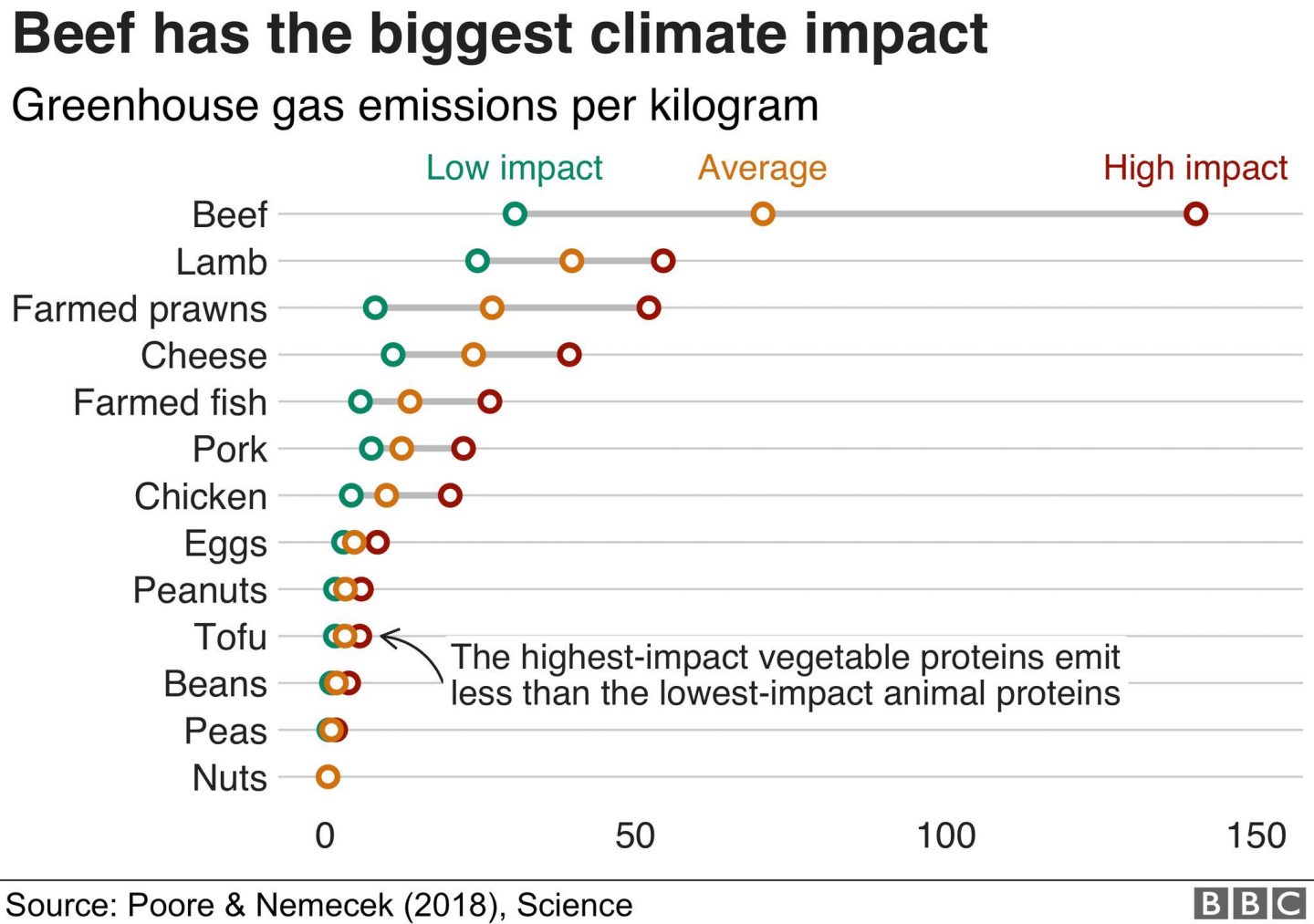

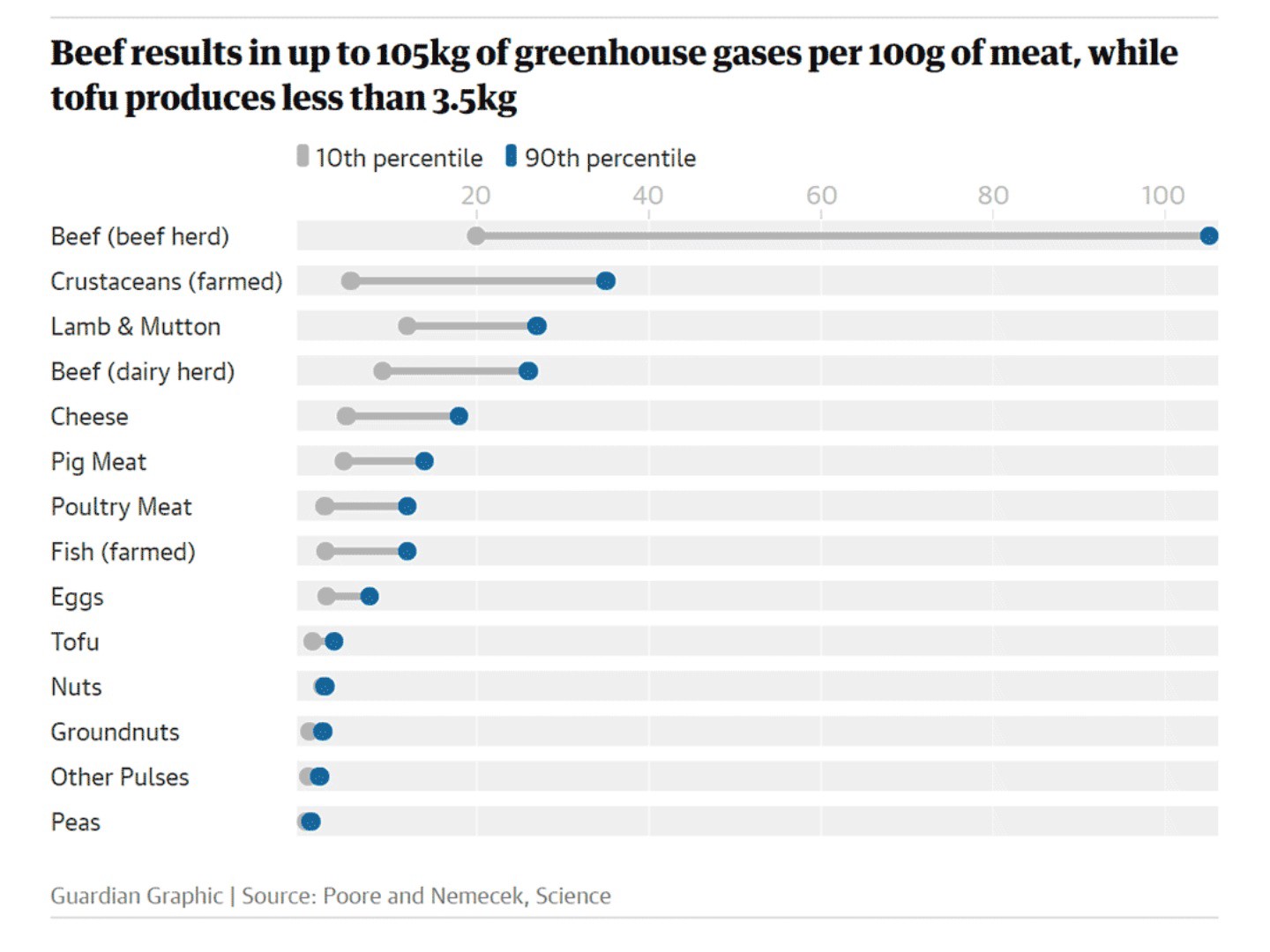

This analysis finds that animal agriculture is responsible for at least 37 percent of GHG emissions.

Overall, animal farming for food contributes more GHG emissions than the fossil fuels burned to power all planes, cars, boats, trains, buses, and other vehicles.

Using a 20-year time frame for methane, addressing the urgency of climate change increases animal agriculture’s total anthropogenic GHG emissions to what it should be. In a speech given at Lewis and Clark Law School in 2010 by Robert Goodland, who directed environmental and social impact assessment studies on development projects for more than 40 years and co-authored the pivotal 2009 Worldwatch report, respiration GHGs can be considered “a proxy for carbon absorption foregone in land set aside for livestock and feed production.”

The conclusion on a final percentage is a conservative value as there are no published values to be found for carbon absorption lost in land cleared for livestock and feed production. Based on these methods that did not include the possible 13.7 percent of GHG emissions attributed to livestock respiration, one can determine that animal agriculture is responsible for at least 37 percent of GHG emissions.

Beyond GHG emissions, our current food system is creating many global issues. In Hawken’s extensively detailed and comprehensive proposal to reverse global warming, called Project Drawdown, the food system was ranked the highest in its potential to reduce emissions. Of the top 20 solutions, eight related to food. Based on that analysis, decisions about what we consume are the most significant contributions we can make to reversing global warming. With this analysis, what we are eating today can be considered the number one cause of global warming.

Although a significant global problem is anthropogenic GHG emissions, the animal agriculture industry’s environmental issues are comprehensive and far-reaching beyond these emissions. Livestock occupies 45 percent of the global surface area, yet on average, 90 percent of land-based livestock are raised primarily confined to factory farms.

Beyond the land used for raising livestock, an essential extra consideration is the food crops that go into feeding livestock. The land use of livestock increases by 10 percent globally to 55 percent when feed crops are taken into account. Furthermore, 65-80 percent of previously forested land in the Amazon is occupied by pastures and feed crops.

In the United States alone, nearly 70 percent of overall grains, 70 percent of soy, and 60 percent of corn production is fed to livestock. As of 2003,

The US livestock population consumes more than seven times as much grain as is consumed directly by the entire American population.

The current global livestock population requires at least 80 percent of the world’s soybean production and more than one-half of all corn. Basic laws of biophysics show that growing feed crops for animals, which people then kill and eat, will never be as resource-efficient, as simply growing the plants for us to eat directly.

When considering GHG emissions, as previously discussed, methane is a particularly important factor. The animal agriculture industry accounts for 35-40 percent of global anthropogenic emissions of methane. These emissions occur via enteric fermentation and manure, which together account for about 80 percent of the agricultural emissions.

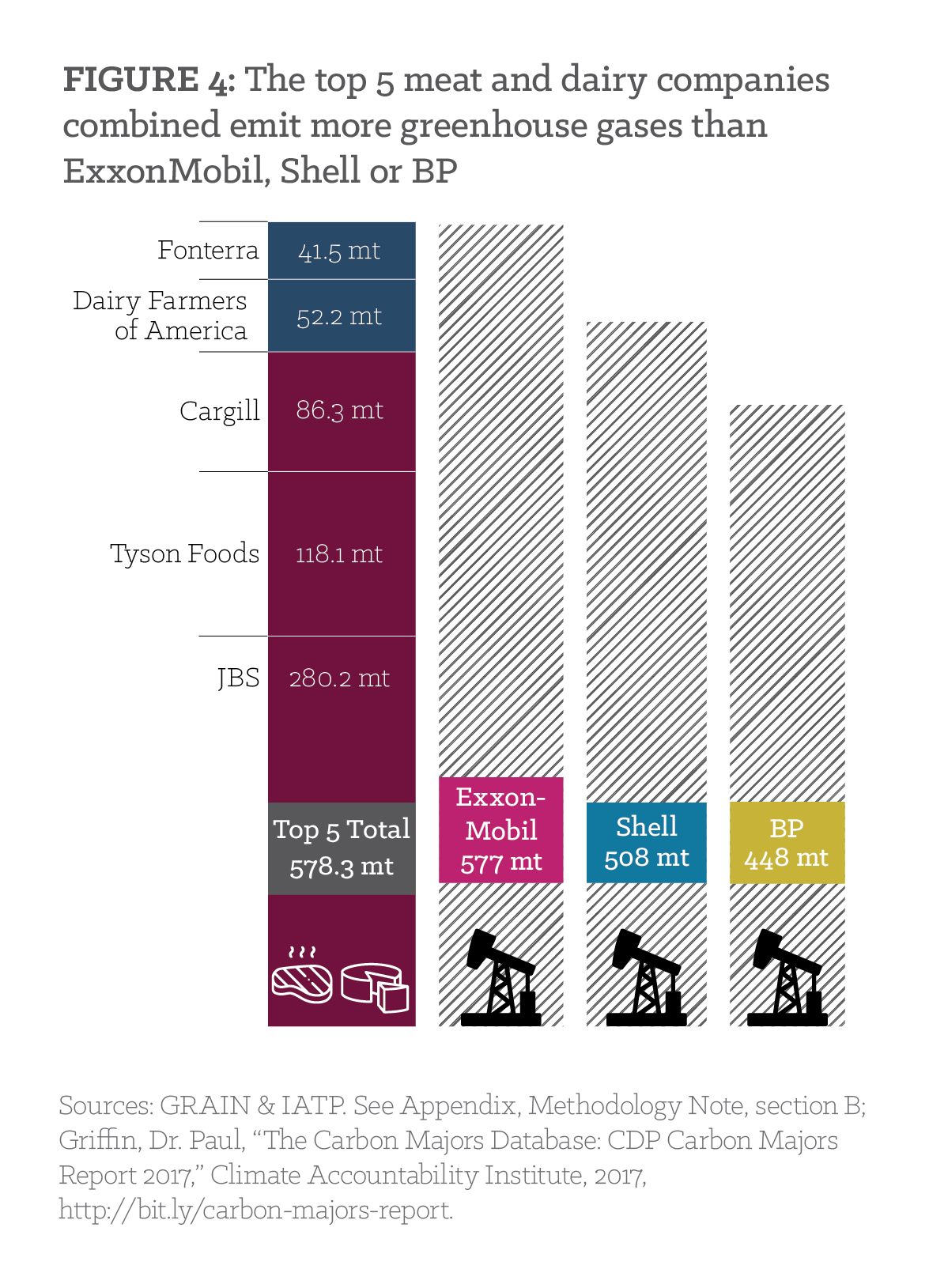

A recent report by the GRAIN and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy found that the five largest meat and dairy corporations combined are responsible for more annual emissions than the oil companies ExxonMobil, Shell, or BP. Yet, government policy and focus seem to be primarily on the transportation and energy sectors.

Concerning biodiversity, many ecosystems are threatened by the current rate of farming animals. Animal agriculture is the leading cause in the reduction of biodiversity, which is mostly from deforestation. Brazil’s Cerrado area, the most biologically diverse savannah in the world, is deforested from the production of half of the country’s soy crops. The wild species diversity in the area is threatened by the rapid increase in livestock feed production and the 40 million cattle per year that this region produces.

The contribution of animal agriculture to anthropogenic GHG emissions and overall environmental degradation is well documented, especially in recent years. In 2018, researchers from the University of Oxford and Swiss environmental monitoring program Agroscope created a massive dataset from 40,000 farms in 119 countries. Together, they analyzed 40 food products representing 90 percent of what is eaten worldwide. A full impact assessment on not just GHG emissions, but also land use, freshwater use, and water pollution, led to their conclusions that a vegan diet shows to be the best way to reduce an ecological footprint.

A report by The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) included input from over 150 experts from 33 countries. They concluded that the entire “agri-food value chain” – which includes agriculture-related deforestation, farming, processing, packaging, transportation, and waste – contributes 43-57 percent of GHG emissions. There is an environmental imperative that needs to be addressed.

Increasingly, scientists are finding that the contribution of animal agriculture to climate change needs to be a more significant focus. For example, a record number of scientists co-signed a published journal article released in October 2017 from the Alliance of World Scientists. This group of more than 15,000 scientists from 184 different countries offered their concerns for the current damage to the environment. The group concluded that promoting plant-based options should be a major focus.

There are major economic considerations regarding animal agriculture. The industry’s financial and political influence cascades to many aspects of society. Economically, animal agriculture accounts for 40 percent of the larger agricultural gross domestic product (GDP). The animal agriculture industry employs 500 million people, most of whom live in low-income countries. However, one can point out that a climate breakdown due to GHG emissions and environmental degradations will hurt the livelihoods of billions of people as well.

On a personal income standpoint, research suggests a vegan diet does not cost an individual more than a standard western diet. There are externalities not commonly taken into account when calculating the costs of various foods. If objectively pricing legumes, beans, rice, and nuts, they can be, and in many cases are, much less expensive than dairy, seafood, poultry, or red meat. Even if the cost is close, the differential should not be a barrier to a healthier diet and a more sustainable environment.

Livestock subsidies create an unjustly low price for consumers making choices of what to eat for their sources of protein or nutrients. Between 1995 and 2017, livestock subsidies in the United States totaled $10.8 billion. The bulk of these subsidies were granted from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and were directed towards crops used to feed animals (corn, soy, etc.).

In Canada, billions of dollars are funded into animal agriculture in the form of gifts like the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Growing Forward funding programs. This program provided $3.8 million dollars to build the Canadian Beef Centre of Excellence whose goal is to increase beef production and sales. These governmental subsidies are not aligning with environmental and health goals. However, the Canadian government, in 2018, changed this with a significant sign of encouragement when they invested $153 million in the growing market of plant-based proteins. This funding was matched dollar for dollar by the private sector and is projected to create 4,500 jobs and more than $4.5 billion to Canada’s economy over 10 years.

Taxes are not uncommon to curtail unsustainable behaviors. In Canada, 35 percent of the price of gas at the pump is part of a tax program which serves as a disincentive to consuming more fossil fuels. Governments in Denmark, Sweden, and Germany are already discussing ways to implement a meat tax in order to address environmental concerns. Overall, western economic programs are inadvertently promoting products that have health, environmental, and social cost that is not internalized into the product. This is especially important when sustainable alternatives exist for consumers. Addressing animal agriculture’s economic externalities that skew the true cost is needed.

When dealing with a global topic like the anthropogenic GHG emissions of animal agriculture, it can be very difficult to narrow down precise statistics. This becomes more difficult when various studies omit entire sectors like aquaculture and animal by-products like fur or leather. This article compared the impacts of animal agriculture as a whole, which in some cases was comparing livestock without the fur or leather impacts, and in some cases with total animal product production impacts.

One major limitation when narrowing down an exact estimate of the global percentage share of anthropogenic GHG emissions that animal agriculture is responsible for is using the same methods across all industries. For example, the equal value for methane needs to be agreed upon and used among all stakeholders. The Worldwatch report notes that more research is needed to increase the world’s total GHG level from non-livestock sources of methane.

An agreed-upon life cycle assessment, from raw materials and production to transportation and consumption, also needs to be adopted to ensure something like deforestation for livestock feed crops is not associated with general deforestation. Until an agreed-upon standard of measure is approved by all industries, a breakdown of various sectors’ contribution will continue to be variable.

What was the motive for authors of the Worldwatch report to point out the issues with the 14.5 percent GHG emissions attributed to animal agriculture by the FAO? The organization they work for is the World Bank and International Finance Corporation, which have the same status within the UN as the FAO. Both are specialized agencies of the UN. It can be speculated that their report did not have a level of professional look and feel: their references were found on a separate link, and there were a few that needed updating. Goodland, one of the Worldwatch report authors, passed away in 2013 and was unable to adequately defend his earlier article even though he did make many presentations and updated articles supporting his work.

The Worldwatch report makes some great recommendations. However, it oversimplified the idea that reducing animal product consumption is an easier way to achieve climate change goals globally than implementing renewable energy technologies. This does not take into account the deep-seated cultural and psychological beliefs that eating animals is normal, natural, and necessary. However, changing our food system does require much more attention than it is currently being given within governmental strategies locally and globally.

Some people believe that there has always been an ethical need to consider non-human animals as sentient beings like humans. However, it has not been until the last few decades that the urgency to address climate change has grown. The contribution that animal agriculture has to climate change is now understood to be significant and can no longer be ignored by policymakers or consumers.

Efforts by consumers to reduce their animal product consumption as much as practically possible is a significant solution. Efforts by government and agencies to take leadership in promoting policy that creates accessibility to sustainable foods for people is another considerable solution.

There is a robust and sustainable business case for a shift of the entire food industry towards viable alternatives, and this can happen immediately without waiting for any new technological advancements. Replacing animal agriculture products with better plant-based alternatives creates opportunities beyond decreasing GHG emissions: land restoration, carbon sequestration, and the reduction of environmental degradation.

Additional analysis and full references found here.

Edited for clarity on October 12th, 2019.