Investigation

‘You Feel Like You’re Marked’: Salvadoran Workers at Tyson Foods Face Risks Due to Work Permit Delays

Policy•9 min read

Reported

Supermarkets often will not open stores in low-income neighborhoods, further limiting access to nutritious foods for their residents. Two California communities are taking a stand.

Words by Kala Hunter

Affluence and access to a better quality of life have been historically linked. People in wealthy, high-end neighborhoods have easier access to walking and biking trails, farmers’ markets, and food co-ops that offer them a choice of nutritious foods, while people in lower-income neighborhoods are frequently housed in proximity to industrial sites and often experience poor air quality and less green infrastructure, with limited access to healthy and fresh produce. The disparity in the quality of life and lack of nutritious food choices feeds a cycle that further exacerbates social and environmental justice issues by creating communities of unhealthy residents who have easy access to fast-food outlets and convenience stores.

Up until a decade ago, this was painfully apparent in two neighborhoods in San Francisco and Oakland, Bayview-Hunters Point (BV-HP) and West Oakland. While locals in both neighborhoods are now changing the narrative of what it means to eat healthily and locally in the form of vegan restaurants and food co-ops, a closer look at the policies that have historically limited their access to healthy food choices reveals another unfortunate legacy of racism, that of supermarket redlining.

Supermarket redlining describes the disinclination of supermarket giants and companies to serve low-income communities: they do so by refusing to open stores in select neighborhoods or shutting down existing outlets and relocating to wealthier suburbs. The origins of supermarket redlining can be traced to the racist redlining practices that came into being in the 1940s, post-WWII when towns and cities in the north saw an increase in migrants from the rural south.

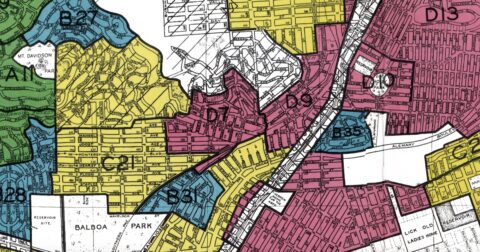

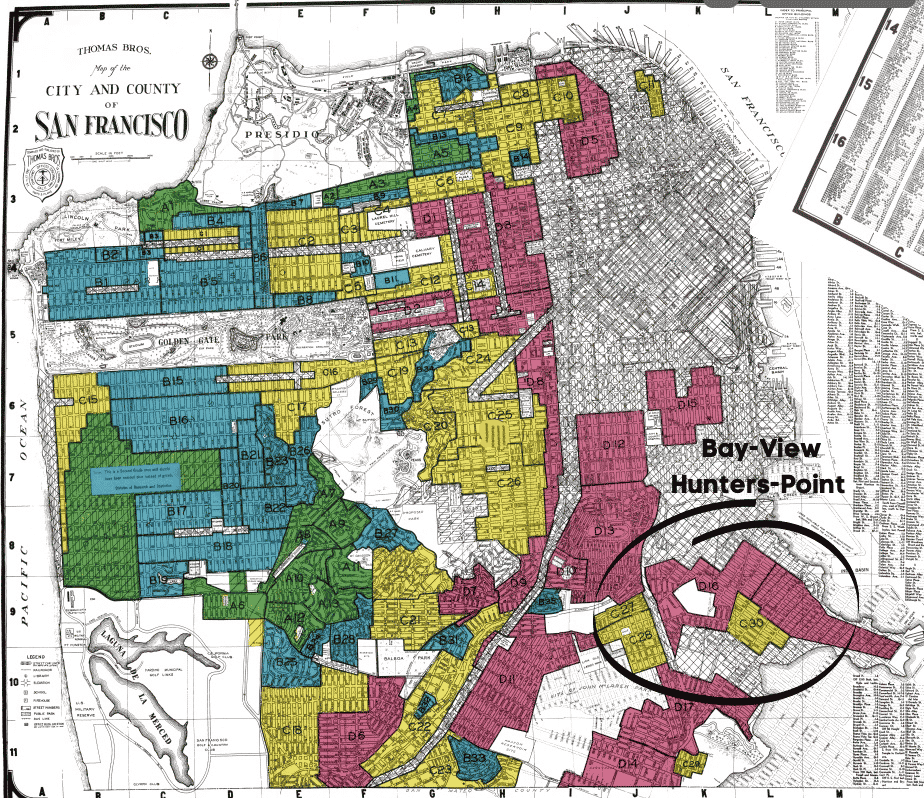

Often referred to as the Second Great Migration, this mass movement of people was an attempt to escape Jim Crow laws and seek new opportunities in towns, and the migrants settled across neighborhoods in these cities. In response, the Home Owners Land Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency created under the New Deal, introduced a grading system that marked the neighborhoods that the migrants settled in. The color-coded grades A, B, C, or D. were used as a guide by which loan officers and real estate professionals evaluated mortgage lending risks.

While people in the green “A” graded districts were most likely to get loans to own a home, the areas marked with the lowest grade of “D” and colored red were considered a lending risk and labeled “hazardous.” The targeted ‘redlining’ ensured that the economically poor black, indigenous, and other people of color or BIPOC communities stayed poor by denying them credit and access to better futures and also made way for fast food giants to move in and retail grocery stores like Safeway and Whole Foods to opt-out of conducting business in the two neighborhoods.

Fast forward eighty years. The neighborhoods of BV-HP and West Oakland are among some of San Francisco and Oakland’s low-income communities. In 2021, the U.S. Census recorded Oakland/Alameda County as being 15.8 percent below the poverty line. In BV-HP the poverty rate is at 13.9 percent. Both counties have poverty levels that are above the national average of 12 percent. As a direct result of the racist redlining policies of the 1940s, the BIPOC communities have stayed poor with limited access to a healthy quality of life, including food choices for over 70 years.

As of 2021, the 34,000 people that reside in BV-HP have access to ten grocery stores with names like Star Market, Big Save, Super Save, and more. There are zero food co-ops. There are, however, several fast-food restaurants.

There is one farmers’ market that accepts a form of supplemental income for low-income households called Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) on Saturdays from 9 am – 12 pm. It is open from May through October. Over the past decade, restaurant owners and chefs in these neighborhoods have been steadily working towards rewriting what it means to have access to healthy food choices and the importance of food education.

Foundations such as The Vegan Hoodchefs in Bayview stress the importance of affordability, education on food justice, nutrition, and health as part of their business. Launched in 2017, The Vegan Hoodchef reiterates, “The goal is to teach communities of color that healthy food options can be flavorful and creative.”

In West Oakland, a similar story has unfolded. According to As You Sow, a leader in shareholder advocacy headquartered in Oakland, “There are no Safeway stores in West Oakland except for a Pak ‘n’ Save, a low-end chain owned by Safeway, which is actually located in nearby Emeryville.”

There is a need for more community-owned initiatives such as a worker-owned cooperative in West Oakland, Mandela Grocery Cooperative, which is celebrating its 12th birthday and is another testimony to the change that is occurring in the neighborhoods. Tackling the low-income, low-access, and ownership issues for West Oakland, the co-op sells organic and local produce, holds high ethical standards for trade, offers cooking classes, and by definition, gives equity when becoming a member.

According to their website, “Prior to Mandela Grocery Cooperative opening in 2009, there were no grocery stores on 7th Street since the 1960s.” There are very few healthy, restaurants in West Oakland. However, on the other side of the 880 freeway, (which one would need a car, bike, or bus ticket to get to) there is one woman who is pioneering accessible, vegan, healthy, soul food.

In 2009, a black-owned, and women-owned vegan restaurant, Solely Vegan, opened on the other side of 880 freeway near Jack London Square. This restaurant is also just outside of Bay View in San Francisco. Tamearra Dyson, owner of Solely Vegan, explains why her restaurant is both sustainable, healthy, and fairly priced.

“We try to keep pricing that will serve both the well-being of the business and also the community, said Dyson. “Food insecurity is something that is deeply rooted in my history. I offer food to those who are hungry (giving leftovers to those who can’t afford). I do think that my prices are fair both sustainable for the business and sustainable for the community.”

The vegan movement as well as the Solely Vegan restaurant have come a long way since its opening. Dyson noted, “When we opened in Oakland in 2009 many in the community did not understand vegan or plant-based. It took a lot of teaching for the people to open up to it. Today, people are now much more educated. They care about what goes into their bodies.” Dyson’s cruelty-free and healthy options enable residents to eat healthier at a fair price.

Perhaps what Dyson and other food justice advocates, chefs, allies, and organizations don’t realize is that they are at the forefront of a mass movement that strives to look beyond race, color, and economic status to enable access to healthy, cruelty-free food. And a movement that can help erase the divisive red lines drawn over 70 years ago.