News

Grasslands and Wetlands Are Being Gobbled Up By Agriculture, Mostly Livestock

Research•4 min read

Perspective

The FDA believes that animal testing is necessary for medical research. But according to lawmakers, researchers, and scientists, that kind of thinking is holding us back.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

This past October, United States Senators Rand Paul and Cory Booker announced they would be introducing the FDA Modernization Act, a new bill to end the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s animal testing mandates. Currently, the FDA requires experimental drugs to be tested on animals before they can enter into human clinical trials. The new bill would allow drug companies to choose alternatives to animal testing such as human cell-based methods instead. Dr. Charu Chandrasekera, founder and executive director of the Canadian Center for Alternatives to Animal Methods (CCAAM), calls the prospect of the bill “incredible,” and hopes Canada will consider the same.

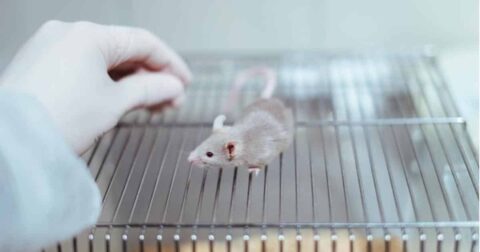

But what makes animal testing so problematic? Don’t we need to test on animals in order to safely and effectively treat horrible diseases that harm humans? Chandrasekera says this is a common myth. “This general public perception, it’s a false dichotomy: my daughter, my grandmother, my somebody, versus this monkey, this rat, this rabbit. ‘I don’t mind if you have to kill the rabbit to save my daughter,’” she describes. While in actuality, animal testing is no longer the necessary evil it once was. In fact, today it is holding us back. Over 90 percent of drugs proven to be safe and effective in animal models fail in human clinical trials. “So it’s not a choice between your daughter or a rabbit,” says Chandrasekera, “it’s a choice between advancing science so that your daughter and your grandmother and your father can have the medications they need, versus holding onto a century’s old paradigm that’s been proven ineffective.”

Work being done by Chandrasekera at CCAAM and others at centers for alternative methods around the world is focusing not on treating rat or rabbit biology, but rather on human biology. Using human stem cells and tissues from cadavers, biopsies, and explanted organs from surgeries, small human organoids can be created on a type of microchip. Cells can even be used to 3D print more complex tissues. This has become known as the “disease-in-a-dish” method, and Chandrasekera believes it is a big part of the future of biomedical research.

And a near future without animal testing is essential, as current methods have evolved to be a massive waste of money, resources, and time. “In the U.S., a major roadblock to medical innovation is FDA red tape that forces pharmaceutical companies to waste years of time and millions of dollars on painful, misleading and outdated drug tests,” says Justin Goodman from tax-payer watchdog group White Coat Waste Project to Planet Friendly News, “and doesn’t allow them to use more modern and efficient research tools.” Goodman adds, “these burdensome government-mandated tests on dogs and other animals fail to predict human drug outcomes 95 percent of the time, causing promising drugs to be abandoned, and dangerous ones to reach patients.”

Chandrasekera agrees, asking, “How many drugs have we tucked away in a back corner of a drug company because they showed some irrelevant side effects in animals? How many things have we not brought to market that could be safe and effective for humans?”

In addition to being wasteful and ineffective, animal testing is also harmful to the environment. A 2014 report entitled Review of Evidence of Environmental Impacts of Animal Research and Testing, published in the journal Environments, states “the quantity of energy consumed by research animal facilities is up to ten times more than offices on a square meter basis.” The volume of waste created by lab animals, and yielded from the incineration of their bodies, also have negative effects on the environment, the research notes. “Evidence demonstrates that their [research animals] use and disposal, and the associated use of chemicals and supplies, contribute to pollution as well as adverse impacts on biodiversity and public health.” Capturing wild animals for use in research also risks throwing off ecological balance and impacting biodiversity.

And of course, animal testing is cruel. Whether for shampoo or mascara or a new cancer drug, millions of animals worldwide are subjected to painful medical tests and procedures simply because they are animals, considered by much of the biomedical community somehow ethically and morally less than humans. But as our understanding of sentience and speciesism grows, this argument no longer holds weight. An ape’s pain, a dog’s pain, a pig’s pain, a mouse’s pain is no different from your pain or mine.

Legislation like the FDA Modernization Act “would be the only way to get these processes, these novel technologies like organ on a chip and disease in a dish adopted by federal agencies,” says Chandrasekera. “That’s where the bottleneck really is.” Because human cell-based methods are there, they have been proven, and more are being developed. But regulators must allow these methods and the data collected from them, to be used.

“The future that I dream about is one where human biology is the gold standard,” says Chandrasekera, “where humans are considered the quintessential animal model, that we base all of our experiments, our hypotheses, and research projects on our biology,” and not theirs.