News

GLP-1 Users Lose Weight, and Their Taste for Meat

Research•3 min read

Feature

Here’s what the latest research says.

Words by Gabriella Sotelo

From climate-smart beef to organic and grass-fed options, the meat industry has no shortage of marketing strategies to sell you meat that sounds sustainable. But the truth is, a sustainable diet for your health and the environment has to mean eating less meat. Now, new research has calculated exactly how much less meat climate-conscious consumers should aim for.

In March 2025, researchers from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) found that to eat sustainably, individuals should consume no more than 255 grams — or about half a pound — of pork or poultry per week. The study also makes clear that beef, lamb and other red meats are not compatible with a sustainable future under current environmental constraints.

“I think this number is in the right range, but (as the authors said) there is not [an] exact cut-off,” Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, wrote to Sentient in an email. “In part because this also depends on the other parts of one’s diet, for example, it might be a little more if someone ate no dairy foods.”

The calculations can get tricky, but the research used simulation modeling to determine how different diets impact the environment and human health. They tested over 100,000 variations across 11 different diet types to identify which combinations meet nutritional needs while staying within what are called “planetary boundaries.” Planetary boundaries are the environmental limits that keep Earth’s systems stable, such as greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water consumption and biodiversity loss.

“Most people now realize that we should eat less meat for both environmental and health reasons,” Caroline Gebara, postdoctoral researcher at DTU Sustain and lead author of the study, said in a press release. “But it’s hard to relate to how much ‘less’ is and whether it really makes a difference in the big picture.”

The research, published in Nature Food, set out to model potential diets that meet two simultaneous goals: human nutritional needs and environmental constraints. The study highlights that “current food systems fail to provide sufficient and healthy food for all, with significant inequalities in access and use driving severe health issues.”

To tackle this, the researchers developed an optimization model incorporating detailed nutritional requirements alongside environmental impact thresholds based on planetary boundaries. Using a dataset of over 2,500 U.S. food items, they assessed diets against five key environmental indicators: climate change, land use, water consumption, freshwater eutrophication and biodiversity loss.

To make sure the proposed diets weren’t just good for the planet but also good for people, the researchers built in nutritional requirements for key vitamins, minerals and macronutrients. That included harder-to-get nutrients in mostly plant-based diets, like B12, vitamin D, iron and calcium. Fortified foods and supplements were factored in to fill those gaps without compromising overall nutritional quality.

To measure health impacts, the team used the Health Nutritional Index (HENI), a tool based on Global Burden of Disease data that estimates how many minutes of healthy life are gained or lost by eating specific foods. A higher HENI score means more time added to healthy life expectancy.

The model generated over 100,000 feasible diet options across eleven dietary patterns, eight matched their criteria of being environmentally and nutritionally sustainable, which included both meat-containing and meat-free diets. The results showed that healthy diets that also protect the environment are indeed achievable, and there are plenty of ways to eat your way there.

The optimized diets, or those that scored highest on HENI while staying within environmental limits, were largely plant-based, with high servings of grains, vegetables, nuts, seeds and fruits. They also significantly reduced meat — especially red meat — and reduced dairy intake.

Willett told Sentient by email that the study’s meat limits are “in the right range,” but emphasized that there’s no single number that applies to everyone.

For example, Willett’s own research suggests that about one serving of red meat per week — or roughly 100 grams — is a safer threshold for reducing the risk of chronic disease, particularly type 2 diabetes. Still, he advocates for mostly plant-based eating, though debates in the nutrition field about the role of red meat have long been quite spirited.

“Keeping intakes at that level, and instead emphasizing plant sources of protein such as nuts, soy foods or beans, is associated with many health benefits including lower overall mortality,” he added, noting that this approach also aligns with traditional diets like the Mediterranean diet.

Compared to the average U.S. diet, these optimized diets could reduce carbon emissions by up to sevenfold and improve health outcomes by adding up to 700 extra minutes of healthy life per week. Based on HENI, the average U.S. diet scores low, likely because Americans still eat more beef than any other country in the world. In comparison, vegan, vegetarian and pescatarian diets all scored above 600 minutes of healthy life gained per week.

The researchers broke down global environmental limits to understand how much impact the food system can sustainably handle overall, and how much an individual’s daily diet can contribute without crossing safe boundaries. For example, their model suggests that to stay within planetary limits, a daily diet should produce no more than about 0.8 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent and use no more than 4.3 square meters of arable land.

Keeping land like forests and grassy savannas in an uncultivated state, rather than deforesting it for farmland, is essential for staving off the worst effects of global warming. Unfortunately, we haven’t made much progress on this front and, in fact, the land problem is getting worse. As Michael Grunwald, journalist and author of an upcoming book We Are Eating the Earth, writes in The Atlantic, “the number of people on Earth increases every day, while the amount of land on Earth does not. But it’s also because those people are eating more meat, which means not only more methane emissions from cow burps and manure, but the use of more land to grow grass and grain for animals to eat before we eat them.”

What can individual eaters do? The research, according to Gebara, highlights that sustainable eating is not an all-or-nothing choice. The study found sustainable eating, as defined by this research, doesn’t require a rigid exclusion of all meat and dairy.

“Our calculations show that it’s possible to eat cheese if that is important to you,” Gebara said in the press release. “The premise is, of course, that the rest of your diet is then relatively healthy and sustainable.” This means individuals can tailor sustainable diets to their preferences without compromising health or environmental goals.

The study’s models show that shifting from the current average U.S. diet, which has a carbon footprint of about 35 kilograms of carbon dioxide per person per week, to one of the optimized plant-forward diets could cut emissions by up to seven times, dropping to just 5 kilograms of carbon dioxide per week.

The eight diet types included in the study range from low red meat and white meat diets to pescatarian, flexitarian, vegetarian, lacto-vegetarian, ovo-vegetarian and vegan diets. No feasible diets were found for high red or white meat consumption, leading the model to cap meat intake at about 255 grams of pork and poultry — roughly three servings — per week.

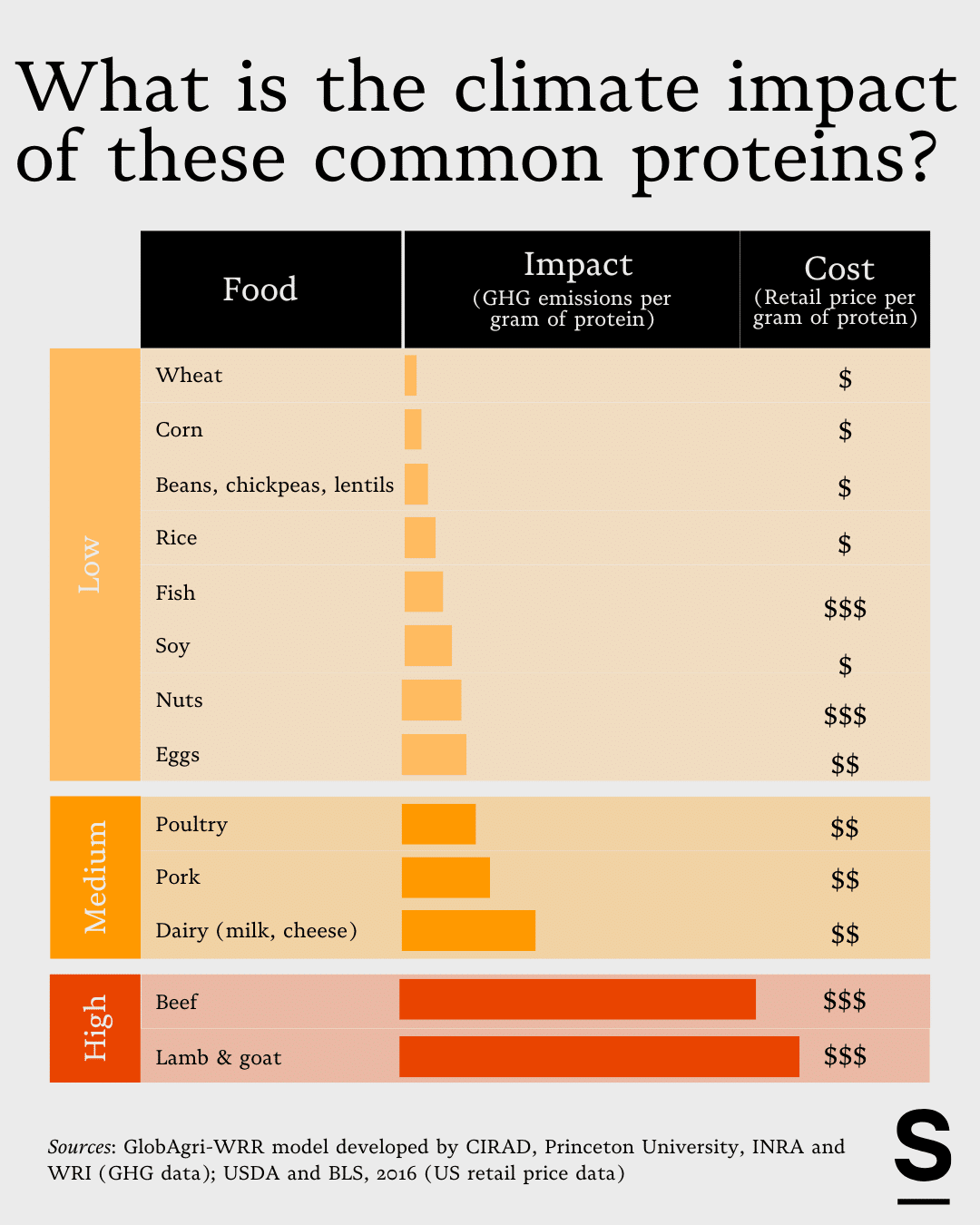

One of the clearest takeaways from the study is that beef, and red meat in general, is a major obstacle to achieving sustainable diets within planetary boundaries. The environmental impacts of beef, particularly its carbon footprint and land use, far exceed those of other protein sources.

Around one third of all global greenhouse gas emissions come from food production, and most of those food emissions are driven by meat, with beef as the main culprit. Livestock production is responsible for between 11 percent and nearly 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions from food production. Because of this, eating even moderate amounts of beef just isn’t compatible with a sustainable diet.

While making the switch from red meat to poultry or pork helps by some metrics, like climate pollution, the researchers factored in other considerations to arrive at their conclusions. The study’s recommended weekly meat limit, for both personal health and climate, is just 255 grams of pork or poultry. That is 6-10 times less meat than most Americans or Europeans currently consume. While the study found that diets that include white meat may support short-term health gains, they do cost us in other environmental impacts.

Americans now eat more chicken than beef or pork, a type of protein that the World Resources Institute characterizes as medium for greenhouse gas emissions on their protein chart (much lower than beef and lamb). The tradeoff in eating more chicken, however, is that chicken farms tend to be far worse for animal welfare, as well as other environmental impacts. A farm that raises 600,000 chickens can generate 72,000 pounds of nitrogen from their waste, for instance. This waste pollutes waterways, and the manure can cause harmful algal blooms.

For industrial hog farming, one year of operation with just 800,000 pigs can produce 1.6 million tons of waste. When manure is poorly managed, it releases ammonia and other pollutants, posing serious health risks to nearby communities. For example, in North Carolina, fecal matter particles have been found traveling through the air and into people’s homes, where residents face elevated risks of respiratory problems.

This difference between what a typical American eats and the recommendations highlights just how far current diets, especially in the Global North, must change to become sustainable.

As governments and food companies scramble to meet sustainability targets, vague calls to eat some less but “better” meat no longer cut it to keep the planet healthy. To stay within planetary boundaries, we need to drastically reduce meat consumption, especially beef.

But the findings also offer a path beyond all-or-nothing thinking. It’s clear from the study that sustainable diets tend to rely heavily on plants, and the research identified multiple diets that meet health and environmental goals, from pescatarian to flexitarian to vegetarian.

Crucially, combatting climate change by addressing food systems isn’t just about individual choices (though some individual actions like eating less meat and cutting food waste do make a difference!). Personal responsibility alone won’t get us the whole way there. As the study emphasizes, “Achieving truly sustainable diets requires universal availability, which must be supported by policymakers at all levels.” Without clear policies and support from our institutions, consumers are left guessing, and the status quo remains.