Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Feature

Current and former employees describe a punishing pace of work and questionable safety standards.

Words by Garrett Yalch, The Frontier

It was just before 3 a.m. in March when the hum of machinery at the OK Foods poultry plant in Heavener was broken by a haunting scream, according to one worker.

That night, the sanitation crew included 49-year-old Leovigildo Ramirez Castillo, a father and immigrant from Mexico. While working above a massive auger — a screw-shaped machine that strips meat from chicken bones — Ramirez slipped through a grated floor and fell into the blades, local media reported. A co-worker rushed to shut off the power, according to a police report, but emergency responders declared him dead at the scene.

His death shines a light on the hazardous conditions faced by the thousands of workers, many of them immigrants, who keep eastern Oklahoma’s poultry plants running at breakneck speed — jobs that are often low-wage and high-risk.

The Fort Smith, Ark.-based company OK Foods, now a subsidiary of Mexican poultry giant Industrias Bachoco, employs over 700 workers at the plant in Heavener and many more contract workers. Ramirez was one of those contractors. He worked for Tennessee-based QSI LLC, which staffs the plant’s nighttime sanitation crew.

Current and former employees describe a punishing pace of work and lax safety standards at the poultry plant, especially for contract sanitation workers.

Months before Ramirez died, a clerk for QSI stepped down from her role on a workplace safety committee. She later alerted a human resources representative for the company that she was concerned about a lack of training and protective equipment at the Heavener plant.

In September, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration assessed QSI $250,628 in proposed penalties after Ramirez’s death. Inspectors who visited the plant shortly after the incident alleged that the company willfully ignored federal rules that require dangerous machinery to be disabled while it is being cleaned and did not provide guards to protect workers from moving parts. Inspectors also allege that the company failed to report injuries that required workers to miss work or be reassigned roles.

OSHA may reduce proposed fines based on the gravity of the violations or if it believes employers are acting in good faith, according to an agency factsheet.

A spokesman for QSI, Gene Boulware, said the company could not comment on the case because the OSHA investigation remains ongoing. He also declined to answer questions about the company’s work with Bachoco given a confidentiality clause in its contract and company policies.

“We are saddened and our hearts go out to the entire Ramirez and QSI-Heavener Families,” said Boulware. “QSI values our associates and works to provide economic empowerment opportunities to those who are often denied access to the American dream … We work to make the food you eat safe, never forgetting the importance of work safety.”

Bachoco also declined to comment on the case because it is under investigation.

“We deeply regret the loss of Mr. Leovigildo Ramírez Castillo and extend our sincere condolences to his family, friends, and colleagues,” the company said in a written response to The Frontier’s questions. “The health, safety, and proper maintenance of our facilities and equipment are fundamental to protecting our employees. We comply with rigorous protocols covering industrial safety and machinery maintenance. We strictly adhere to federal regulations and international standards, as well as all applicable local regulations, thereby safeguarding the well-being of our staff. Our management team holds the certifications required by the relevant health and safety authorities.”

To investigate safety hazards in the plant, The Frontier spoke with nine current and former employees, including workers from Mexico and Central America, and reviewed internal emails, autopsy records, inspection data, medical records, police and fire reports, emergency call recordings and other sources.

Cheyenne Priebe, who worked as a clerk for QSI at the Heavener plant, warned executives that the company was failing to provide adequate training and that supervisors had stopped holding required weekly safety meetings, according to a copy of a July 13, 2024, email obtained by The Frontier.

“I am worried about the safety of all future and current employees, and safety does not appear to be a priority to some management,” Priebe wrote.

Workers were made to sign safety forms without reviewing the procedures, two workers said.

Boulware said QSI’s corporate leadership team and human resources compliance hotline has received no complaints involving signing forms and reviewing safety procedures, “despite notices of such contact information posted at all sites, including in Heavener, OK.”

Other workers said they also tried to sound the alarm. Peggy Persons, who was a production worker for OK Foods for two years before leaving in November, said she complained to supervisors about dangerous conditions between eight and 10 times.

“I even told my supervisor at one point, ‘What is it going to take? Is it going to take somebody getting killed up here before you guys pull your head out?’” said Persons, who is now a member of Heavener’s city council.

Former workers said the pursuit of speed led to safety shortcuts at the plant. Federal law requires augers to be turned off and locked down during cleaning, but two former workers, who both quit in 2024, said that during their time working there, supervisors routinely left them running so crews could hose them down faster.

“We would tell them all the time, don’t run machines while you’re cleaning,” said Brian Layman, a longtime maintenance manager for OK Foods who quit last year because of an injury.

QSI said it had no record of such complaints and that the company requires procedures to keep machinery shut down and secure.

“Our policies and procedures are fully compliant with all relevant regulations and standards,” the company said in response to questions. “Additionally, QSI provides and requires all managers to post a flyer encouraging all employees to report any unsafe condition using our monitored anonymous reporting email address and phone hotline.”

On the same shift that Ramirez was killed, workers were already caring for another worker who had fallen from a ladder and was bleeding from his head, according to recordings of a 911 call from that night. As voices shouted and an alarm wailed in the background, the caller told dispatchers: “We’ve had a guy fall off a ladder and hit his head, and we got another guy hung up in a machine right now. And the nurse… There is no nurse here.”

The Heavener facility is one of the largest poultry processing plants in Oklahoma and one of four U.S. processing operations owned by Bachoco, which purchased OK Foods in 2011. The company has supplied chicken to Walmart, Raising Cane’s, KFC, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut.

Oklahoma leaves workplace safety oversight to the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The Trump administration removed requirements that plants report data on worker injuries in 2019, and proposed loosening other federal workplace safety rules earlier this year.

While the larger poultry industry in neighboring Arkansas has given rise to worker centers and advocacy groups that push back against unsafe conditions, Oklahoma’s still sizable immigrant workforce has less support. Poultry plants in the state lack unions or other outside organizations to amplify workers’ safety concerns.

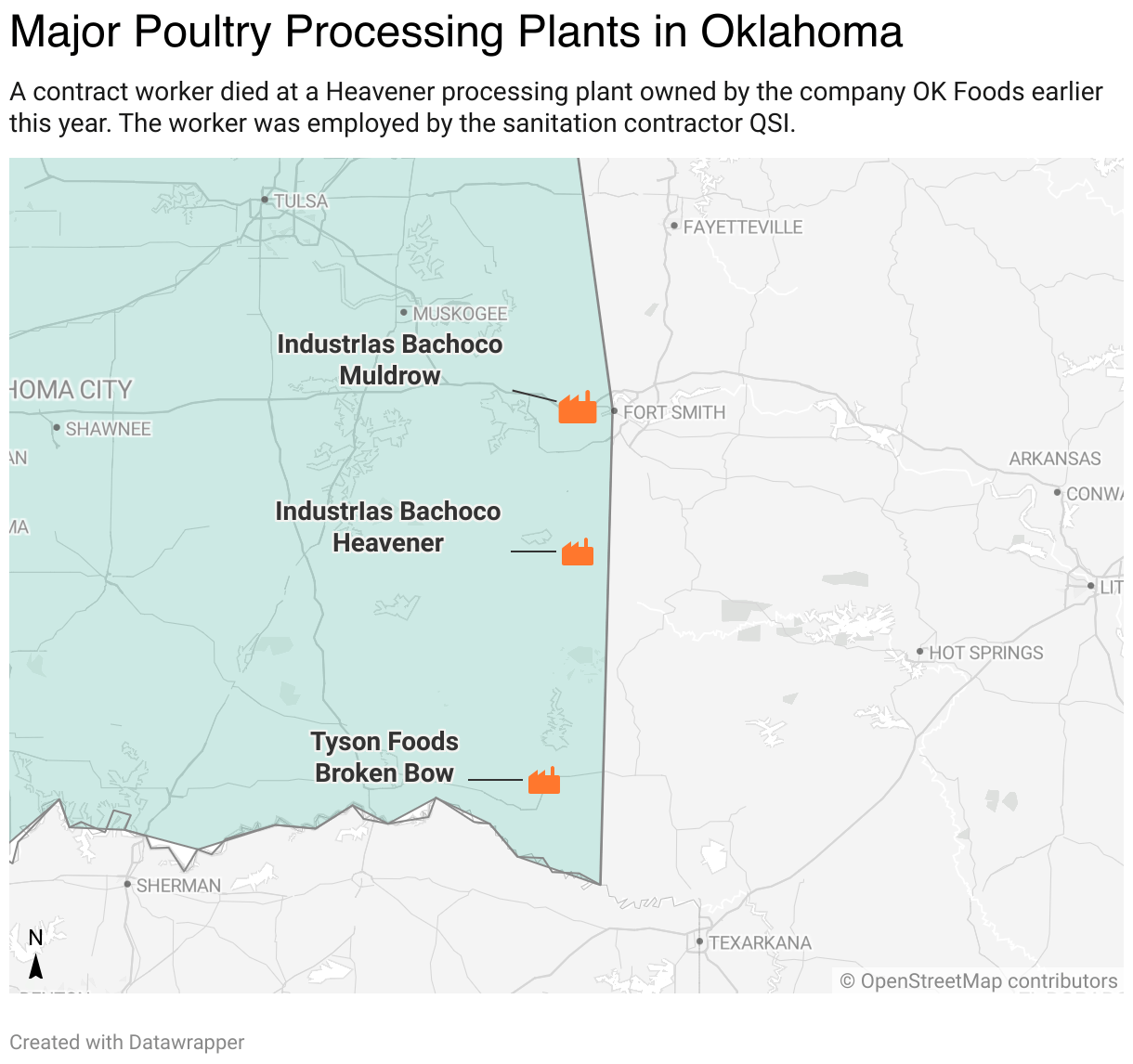

Bachoco has another large plant in Muldrow and Tyson Foods has a major plant in Broken Bow that employs around 1,250 workers.

Ramirez’s death marks the first recorded workplace fatality at Bachoco’s U.S. operations since the company acquired OK Foods, though according to news reports, several workers have died at its plants in Mexico in recent years. Nationally, the poultry processing industry recorded eight workplace deaths in both 2022 and 2023.

Records show that OK Foods has been cited previously for safety lapses in Oklahoma. In 2015, OSHA inspectors cited the Heavener plant after finding “an employee was working from a platform that was not guarded with standard railings, nor was the employee provided with a means of fall protection.” In 2017, OSHA fined an OK Foods plant in Oklahoma City more than $18,000 for failing to document fire risks, maintain ammonia detectors and implement an emergency action plan.

In March 2023, the U.S. Department of Agriculture granted the Heavener plant one of 44 line-speed waivers nationwide, allowing it to process 175 birds per minute instead of the standard 140.

The Trump administration announced plans this March to make faster line speeds a federal standard for meat processing facilities and eliminated requirements that plants with waivers report certain workplace injury data. Labor unions have opposed the new rules, arguing they will increase the rate of injuries.

Since the Heavener plant was opened in the 1990s, immigrant labor has reshaped the small town in the Ozark foothills. Today, over a third of Heavener’s roughly 3,000 residents are Hispanic, with Spanish-language signs along its main street and a Catholic parish that offers services in Spanish. Immigrants work tough jobs throughout the poultry supply chain — from catching chickens on nearby farms to staffing the company’s feed mill.

While earlier waves of workers came mostly from Mexico, employees say the plant has increasingly recruited newly arrived immigrants from Haiti, Venezuela and Central America to meet its demands for labor.

Immigrant workers are often less inclined than native-born workers to report unsafe working conditions or injuries because they fear losing their jobs or being deported, said Jose Oliva, the campaigns director for the HEAL Food Alliance, a coalition of organizations that represent food industry workers.

“It’s like this choice of, ‘Do I continue to risk my life and limb in this plant, or do I try to find work somewhere else that’s going to pay less and that I’m not going to be able to send money home for?’” Oliva said.

When the poultry industry started industrializing after World War II, companies prioritized cheap land and labor, said Angela Stuesse, a professor at the University of North Carolina who has studied how Latin American migration changed Mississippi’s poultry industry. She said many poultry plants opened in rural parts of the South, where resources for workers are scarce, and producers formed a reliance over time on immigrant laborers for their most grueling work.

“This industry is really skilled at constantly seeking out who is the most vulnerable or exploitable population, and how do we bring them in,” Stuesse said.

Medical examiners identified Ramirez using a Mexican voter card, and he used a different first and last name at the plant, documents show. His co-workers knew him as “Ricardo.”

QSI said in a written response to The Frontier’s questions that it “maintains rigorous documentation and identification requirements that exceed federal requirements,” including the use of facial recognition scans.

“QSI has no record of any employee at the Heavener location, or otherwise, not meeting our compliant identity policies or failing any such scan,” the company said.

Ramirez was married to a local woman and had three daughters and a son. He worked in the mechanically separated chicken department, one of the plant’s more dangerous areas, according to two workers. Ramirez’s family has hired an attorney and court records indicate they plan to file a wrongful death lawsuit. His widow declined to be interviewed for this story. The family’s attorney said he could not comment on the case until the lawsuit is filed.

Hailey Breseman, who worked the shift after Ramirez died, recalled the aftermath. When she first arrived at the plant, she said it was work as usual.

“We’d been there for several hours before they actually pulled us off the floor and were like, ‘Hey, just so y’all know, we actually do care that your co-worker died. Sorry, we didn’t say anything,’” she said. “It was like an afterthought.”

This story was produced in collaboration with Tulsa Flyer.

The Frontier is a nonprofit newsroom that produces fearless journalism with impact in Oklahoma. Read more at www.readfrontier.org.