Feature

The Sneaky Way Even Meat Lovers Can Lessen Their Climate Impact

Food•6 min read

Perspective

New technology is making farmers' lives easier, but the increased efficiency they bring often comes at the cost of farmed animals.

Perspective • Food • Industry

Words by Karen Asp

Strapping virtual reality (VR) headsets on cows might seem like something you’d see only in a Saturday Night Live skit. Yet, as they say, truth is often stranger than fiction, and in this case, cows being raised as food in places like Russia and Turkey are indeed wearing VR headsets.

These cows, though, aren’t trying to perfect their scores in Beat Saber or travel the world to get fit via Supernatural, two popular VR apps for people. Instead, farmers say they’re using VR to enhance the cows’ mental well-being and make the animals think they’re outside, according to an article in Newsweek.

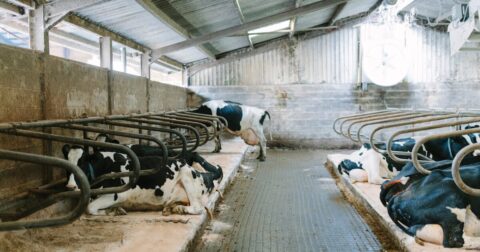

VR headsets are just one example of the technological innovations, often called smart farming, changing the face of animal agriculture. And while you might take the farmers’ words at face value and believe that these so-called advancements are improving animal welfare, you’d undoubtedly be hard-pressed to find many farmed animals who would agree.

So just what impact does smart farming have on farmed animals’ well-being? That’s a question still being teased out, and the answer isn’t as clear-cut as you might initially think.

“With rising public concern for animal welfare across the world, some people see the efficiency gains offered by the new technology as a direct threat to the animals themselves, allowing producers to get ‘more for less’ in the interests of profit,” writes Marian Stamp Dawkins, a professor at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, in Frontiers in Animal Science. “Others see major welfare advantages through life-long health monitoring, delivery of individual care and optimization of environmental conditions.”

It sounds like a double-edged sword—until, that is, you consider the price farmed animals are paying. What you learn, in terms of animal welfare, is that smart farming is little more than window dressing, just another fancy way to veil the massive problems behind farm walls.

As its name may imply, smart farming is the use of technology in animal agriculture, and it’s something that’s been around since the Industrial Revolution. The biggest difference between then and now, though? “Motorized devices are being replaced with artificial intelligence (AI),” says Ben Williamson, U.S. executive director of Compassion in World Farming, an organization aiming to end factory farming by 2040.

As a result, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), which is where Sentience Institute estimates that roughly 99 percent of U.S. farmed animals live, can automate more easily, using technology like smart robotic feeders and robotic milkers for dairy cows. Data about the environment inside factory farms and the animals themselves can also be collected more readily. For instance, sensors linked to computers could indicate if the equipment is malfunctioning, and smart wearable tags and trackers on the animals (think of them as Fitbits for farmed animals) could reveal potential health issues and spot early signs of illness. And while VR headsets are undoubtedly too costly to provide for every farmed animal, they’re another way technology is changing the way we farm animals.

The above examples only touch the surface of how technology is being used in the animal agriculture industry, but no matter the mode, the goal is the same. “Smart farming is designed to increase the yields and productivity from farmed animals,” Williamson says. And there’s proof it’s working.

For instance, a farmer in Turkey was quoted in the Newsweek article as saying that prior to using VR headsets with his cows, he was getting 22 liters of milk per day. Yet after two of his cows used VR headsets, which he says gave them an emotional boost and lowered their stress because they were watching green pastures, their average milk production rose to 27 liters. And in an article posted by the European Commission, the author points to one study which found that when cows were outfitted with smart ear tags and feeders, milk yield increased by one percent and milk quality by 20 percent.

Companies producing smart farming technology do mention improved animal welfare as one benefit. But Dawkins argues that whether smart farming improves or damages animal welfare will depend on three factors. “Three developments will be crucial to the ethical evaluation of smart farming in its treatment of animals: the definition of ‘welfare’ it adopts, computer recognition of welfare, and crucially, whether the welfare of farmed animals is actually improved by the application of smart farming technology,” she writes.

There are, of course, many ways animal welfare has been defined, but no matter the definition, it’s akin to how you would define human welfare. “It essentially comes down to the animals’ happiness and level of suffering,” says Jacy Reese Anthis, social scientist, co-founder of the Sentience Institute and author of The End of Animal Farming. “Animals want to live unconfined, be in good health, and have healthy social relationships, none of which animal agriculture allows.”

Even a step toward better health, something that smart farming promotes, comes with an ulterior motive, namely profits. “If you have sick animals, that’s fewer animals you’ll be able to sell,” says Williamson, adding that Compassion in World Farming engages with the world’s leading food companies to adopt meaningful animal welfare policies while tracking progress against those commitments to ensure compliance. “So animal welfare is a consideration with smart farming, but not in the same way you or I might consider it to be a plus, as the incentive to keep animals alive and healthy revolves around economics, and I think sometimes the purpose of keeping animals alive and healthy enough is just to have more of them to use.”

Ultimately, smart farming could wind up intensifying animal suffering. “Because you don’t need as many humans involved with smart farming, you can increase the number of animals in CAFOs, which means animals will be confined in even tighter spaces,” says Anthis, adding that more animals also means greater disease breakouts, which can lead to health issues for humans. “Any small gains you make in decreasing their suffering will be outweighed by these increases.”

And although things like VR headsets could raise consumer awareness that factory farm conditions are so dire that the industry now needs to turn to VR, that still doesn’t move the needle much for animals.

That’s not to say that all smart farming technology is, for lack of a better word, bad. As Williamson notes, many of these technologies help farmers make use of natural resources better through the use of innovations like precision irrigation and technology that connects smaller-scale farmers with each other.

Yet when it comes to the animals, smart farming seems to be the wrong way to go. “Animals want to live long, happy lives, and even if they don’t realize they’re unhappy, we do and there’s an ethical burden upon all of us to ensure that animals live a good life,” Williamson says. “These technological solutions are not solutions at all but are just compounding a food system that’s sadly driving the planet and a lot of its inhabitants into extinction.”

In the end, until factory farming is abolished, no amount of advancements can ever give the animals what they truly want and deserve: Freedom.