Investigation

Oklahoma’s Loophole: How Tyson’s Water Use Goes Unchecked

Food•15 min read

Reported

Climate change is causing more North Carolina farms to flood, killing animals and flooding the streets with their manure.

Words by Victor Espinosa

Some of the cheapest land in North Carolina sits within the Atlantic Coastal Plain — the more than 2000-mile stretch of the eastern U.S. seaboard that has become especially vulnerable to climate change. Global warming has increased the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, putting the area at very high risk for what The Guardian describes as “super-charged hurricanes,” the kind that hit with little warning.

It’s not just the weather. Duplin County, North Carolina is home to less than 50,000 people, just over 18 percent of whom live below the poverty line, and more than 2 million hog farms. The county was top ranked in the nation for pork earnings in 2012, raking in more than $600 million in sales.

Hog farms are an inextricable part of the climate change story here. After a hurricane, people are sometimes forced to carry their belongings over their heads as they wade through waist-high water to evacuate through flooded streets. But in Duplin, and elsewhere in North Carolina, those flood waters are likely to be filled with hog waste.

The worst case scenario has already taken place multiple times here. In 2016 and 2018, two hurricanes drowned millions of chickens and turkeys and more than 5,000 hogs, according to state department of agriculture estimates. Rivers turned toxic, killing fish and other wildlife.

And it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. This year’s hurricane season was the seventh consecutive in a row of increased storms and hurricanes. To make matters worse, a new report from the Environmental Working Group warns two percent of factory farms are at risk for flooding — more than 156 concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs — 26 in Duplin County alone.

“It’s at its worst now,” says Jamie Berger, writer and producer of The Smell of Money, a documentary that highlights the problems associated CAFOs in North Carolina. “It’s a lose-lose-lose situation for anyone other than these mega corporations.”

Pigs have been farmed in the state since colonial times. Thanks to industrialization and poor regulation however, the state’s pig population exploded from less than 200,000 in the 1980s to now almost outnumbering its human population of more than 10 million. Most of these animals are raised intensively on CAFOs for the multinational pork-producing behemoth, Smithfield.

In March 2022, the state’s hog population was estimated at around 8 million hogs. Adult hogs produce as much as ten times the amount of waste that humans do, according to data from the University of North Carolina. But even though a portion of the 8 million hogs will be slaughtered before they reach adulthood, collectively the farmed swine generate lasting pollution in the air, soil and water for miles around.

Most contract pork producers in North Carolina manage their pig waste with lagoon and spray-field systems. Hog growers could choose to treat their waste in a variety of ways, from composting manure to complex aeration systems. But in reality, very little has changed in the way most North Carolina hog farms handle their manure since the late 1980s.

North Carolina has over 3,400 hog lagoons where hog waste is stored until it can be applied as fertilizer to crop fields.

In the wake of Hurricane Florence, dozens of lagoons burst and contaminated local waterways. A team of researchers from North Carolina State University took samples from 40 different surface water sources. Of the sources tested, 30 percent contained water unsafe for swimming, their main contaminators being Acrobactor and E. Coli bacteria from human and pig waste.

Growers are supposed to stop spraying their fields if they see standing water. In fact, it’s illegal to spray pig waste within 48 hours of a hurricane watch or a severe storm warning. Yet aerial surveillance footage has documented farmers violating these regulations with alarming regularity.

These aren’t new discoveries. In 2001, a paper published by the Natural Resources Defense Council titled Cesspools of Shame detailed each violation committed by the largest CAFOs, the fines they paid – if any – and the consequences of the offense. Countless entries document fish die-offs, illegal spraying of fields already inundated with manure and communities complaining of health problems. It’s the most comprehensive document about the issue of cesspools in America, yet it was written two decades ago. Today, the problem continues unabated. That’s what Berger calls an “entrenched problem.”

Berger’s documentary focuses on the human aspect of CAFOs in Duplin County. The film profiles several families who live next to large-scale CAFO operations, in close proximity to enormous vats of pig waste. “The depth of attachment they had to the land they live on” stuck with Berger, she says, but so did the experience of seeing acres upon acres of untreated waste.

Larry Baldwin, the CAFO campaign coordinator of the Waterkeeper Alliance, says, “the state does very little” to handle the problem. The lack of state regulation on pollution from waste is a difficult problem to overcome. “The [agriculture] industry has the upper hand. They have such a stranglehold on growers, the legislature, and the economy,” says Baldwin. “Reform is not gonna be easy.”

In Baldwin’s view, these cesspools are “a cheap, caveman mentality way of getting rid of waste.”

“The solution has existed for quite some time,” Baldwin says. “It’s called superior technology.” And by superior technology, he means alternative, sustainable treatment methods, like sequencing batch reactors, aerobic granulation and biofilters. Unfortunately, the problem is more complicated than a simple renovation with modern technology. Even one of the industry’s own proposed solutions, methane biogas collection, still leaves almost all the hog waste behind after the gasses are siphoned off.

Any effort to regulate the pork industry in North Carolina inevitably brushes up against China-owned Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork producer and a significant player in North Carolina’s economy.

According to both Baldwin and Berger, lobbyists for Smithfield and other industry groups wield significant influence in the state. “They made it incredibly difficult for anyone to ever sue the industry again,” says Berger. Recent laws passed through the North Carolina legislature all but prevent citizens from suing pork CAFOs for any health, property or environmental damages.

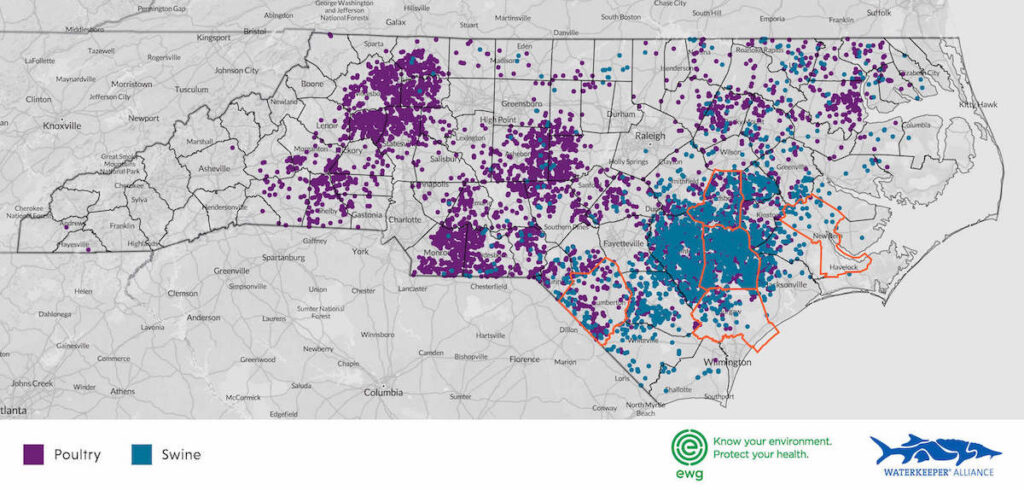

Still one Waterkeeper Alliance victory was the hog CAFO moratorium enacted in North Carolina in 2018, a significant win in a state with almost as many hogs as people. But the agriculture industry has responded by shifting production — increasing the number of concentrated poultry farms in the state, since these livestock operations are subject to even fewer regulations.

Pollution from poultry operations is harder to track. “The only good thing about hog waste from CAFOs [is that] they’re very visual,” says Baldwin. It’s challenging for hog farmers to transport thousands of pounds of untreated liquid sewage.

Even if pro-pork politicians and meat companies continue to score victories in the courts and legislature, they are losing the public image battle, which typically hits contract farmers the hardest. It’s those contract farmers who might offer a path for change.

“If we could just get to the growers, we could make a huge difference,” Baldwin says of the Waterkeeper Alliance’s efforts to educate hog growers on the hazards of CAFO waste. “Not everyone is bad. There are some trying to do the right thing.”

Berger agrees. “Some pork makers are open to changes,” she says. “But their hands are tied and there is lots of fear.” Growers are the vulnerable minority in North Carolina. The contracts signed by growers are designed to keep them subservient. Growers who manage to obtain waste treatment facilities do so out of pocket, and if anything goes wrong, they don’t have the backing of the agriculture industry; they’re entirely on their own.

When any actual change to hog CAFO waste in North Carolina will come is anyone’s guess. There is fertile ground for solutions, though, whether through re-examining the manipulative contracts of CAFO growers, giving legal power back to North Carolina residents or passing laws protecting the environment rather than corporations. But for now, prospects for change in Duplin County remain bleak. Berger, after completing her documentary, is leaving the fight for environmental justice in the hands of younger generations and local activists. And though Baldwin would rather go down swinging than give up the battle, this battle looks to be part of a long, protracted war in which victory is not guaranteed.