News

GLP-1 Users Lose Weight, and Their Taste for Meat

Research•3 min read

Fact Check

At least, not at current rates of meat consumption.

Words by Jessica Scott-Reid

Now that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has kicked off his Make America Healthy Again, or MAHA Commission, food system advocates are wondering which of his ideas will come to fruition. One promise was to revamp the food system with a plan to “reverse 80 years of farming policy.” But what exactly would it mean for the average American to eat like we did in the 1940s? Experts tell Sentient the reality was not as idyllic as Kennedy and his supporters might believe. It’s also not at all feasible, as it would require the U.S. to make drastic changes to the way we eat. To put it bluntly — Americans would have to eat much less meat.

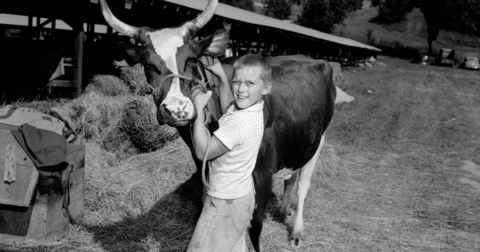

At first blush, the historical picture does sound like locavore heaven. Food systems were still mostly regional, food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson tells Sentient. People living in rural areas were more likely to have access to their own fresh produce, drink dairy from their own cow and can their foods for the winter.

The typical middle class family would eat “very Anglo-influenced foods,” Wassberg Johnson says, like “meat and potatoes and vegetables.” But back then, meat tended to be beef or pork, as chickens were considered a delicacy. That would all change after the birth of the industrial poultry farm, which kicked off the era of cheap and abundant chicken.

Dig a little further into the history and you quickly realize that the amount of meat consumed then was far less than what most people eat today. The average American only ate around 113 lbs pounds of meat in 1945 — less than half of the nearly 230 pounds of meat consumed annually today per capita.

Meats were usually prepared in dishes designed to feed more people with less meat. Home cooks incorporated them into sauces, stews and casseroles. The “quintessential American food,” meatloaf, is typical of this practice of meat-stretching. “You’re taking ground beef, which is already the cheapest meat…and you’re stretching it with onions and breadcrumbs, egg or milk. So you’re trying to stretch a pound of beef to feed more than four people,” Wassberg Johnson says.

People also ate more meat alternatives, even if they weren’t called that. Grains, nuts and beans were common sources of protein. Following the war, dry bean consumption in the U.S. was around 11 pounds per capita annually — compared to just 5.5 pounds per capita in 2023.

Americans were encouraged to grow “victory gardens” to help supplement the national food supply, and beans were an important crop, including soybeans, sometimes called “‘wonder beans’ or ‘miracle beans.’”

And yet, the transition to an industrialized food system was already underway. “There’s a lot of romanticization of food production in the past,” says Wassberg Johnson. “A lot of people are like, ‘Oh, if only we ate how grandma ate, everything would be better.’” But even then, she says, there was heavy dependence on things like railroads for food transport and access, and processed foods like flour, cornmeal, sugar and canned goods.

Americans ate less meat back then, and we produced less meat too. In 1945 — prior to the rise of factory farming — there were just under 6 million farms in the U.S., with each operation ringing in at a little less than 200 acres in size on average.

Contrast that with 2024: researchers counted 2 million farms in the U.S., but the average size is much larger at about 464 acres. Over the decades, farms became more consolidated. Smaller farms merged or went out of business, and larger, more industrialized operations flourished.

The massive growth in industrialized farming was made possible by technology that did not exist 80 years ago, such as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, farms that focused on one or two commodity crops and concentrated animal farming operations, or CAFOs. These developments enabled the U.S. food system to produce massive amounts of cheap meat — primarily chicken — that consumers happily gobbled up.

Industrial poultry operations were first developed in the 1950s. Around 275 million chickens were raised for meat in 1946 in the U.S; by 2023, that number skyrockets to 9.16 billion.

All of that “cheap” meat is not without other costs. Today, 99 percent of farm animals are raised on factory farms or industrial operations with cramped quarters for dairy cows, chickens and pigs. The beef that Americans eat at higher rates than the global average fuels climate pollution and deforestation. CAFOs and slaughterhouses are responsible for polluted air and water, and worker injuries and poor mental health.

So, why not trade factory farming for the good old days of American food — small-scale farms and the agricultural policies of 80 years ago? Sentient asked American agriculture historian and professor at Purdue University, R. Douglas Hurt, whether RFK Jr.’s proposal is at all realistic. “Of course not,” Hurt says, and here’s why.

To turn the U.S. food system back to the small-scale style farming of the early 20th century would be extremely costly for farmers and consumers alike. Small farms, Hurt explains, “historically have not provided enough income to keep farmers on the land.” Farmers need “hundreds of acres to generate a profit and an acceptable standard of living” — with very few exceptions, like “a high value specialty crop such as avocados.”

Small-scale farms — like hobby farms or the homesteads you see on social media — might provide an alternative lifestyle, says Hurt, but they usually aren’t profitable. “To be profitable, the money must come from sources other than free-range chickens, eggs and a few grass-fed beef cattle. Quantity of production matters.”

To revert back to small farms, says Hurt, “the federal government will need to subsidize” those farmers, in order for them to make a living. “This will be very expensive,” Hurt says.

It also might be pretty unappealing. “The good old days, they were terrible,” Hurt says. “Farming is hard work. That’s why so many people leave it if they can for a better job and more money.”

So what if we all turned into subsistence farmers, and grew our own food? Some people are trying to do just that, as I reported on last year, but many learned in the process that raising and butchering their own animals was far more difficult than they had hoped. For some nascent homesteaders, instances of “butchery gone awry” turned out to be cruel to the animals, and upsetting for them.

There’s yet another reason why switching from industrial factory farms to small farms would be a disaster — the environment. Even if we were to only focus on transitioning beef to an all grass-fed approach, at current rates of beef consumption that would require far more land and resources than we have.

In 2018, environmental scientists Matthew Hayek and Rachael D. Garrett found that “a nationwide shift to exclusively grass-fed beef would require increasing the national cattle herd from 77 to 100 million cattle, an increase of 30 percent,” but there simply isn’t enough pasture available.

There is one way a shift to much smaller farms might be feasible, and that’s if we were to drastically reduce how much meat we eat. A transition to a plant-based food system could save an estimated 24 percent of total land use and feed around 700 million people — about double the entire population of the United States.

That doesn’t seem to line up with the way Americans still want to eat meat. And it’s a far cry from the approach RFK Jr. and his MAHA acolytes are championing. A recent interview on Fox News took place over burgers at a fast food chain — one that had apparently agreed to stop serving seed oils. Even if current trends have made RFK Jr.’s plans for taking the food system back in time sound appealing, his ideas are simply not going to play out that way in reality.