Investigation

Meat Processing Plant Complaint Highlights Supply Chain Disruptions — And How the Meat Industry Isn’t Prepared

Food•4 min read

Explainer

Tyson Foods produces 20 percent of the United States’ chicken, pork, and beef products. Their market dominance is won at the cost of cruelty to animals, harm to the environment, and risk to human health.

Words by Taylor Meek

There are probably Tyson products in your local supermarket. Tyson supplies food to restaurants like KFC, Taco Bell, Burger King, and McDonald’s. Their products are also distributed to small businesses and institutional food services like prisons. Tyson Foods is everywhere.

In 2018, Tyson sold $40 billion worth of products, with sales consisting mostly of beef and chicken. Tyson slaughters around 133,000 cows per week within a dozen facilities, 408,000 pigs per week in nine facilities, and 37,000,000 chickens per week in 50 facilities.

Let’s pause on one data point there: 37 million chickens killed per week by just one company.

Being one of the top meat producers in the United States means that production cycles must be fast, animals must be bred in large quantities, and the slaughtering process must be a continuous cycle.

Whenever production times are under pressure, abuse and neglect are likelier to occur. Since workers are rushing animals to transportation trucks or slaughter, a slow or defiant animal might disrupt their quick pace. This hindrance often results in kicking, poking, and stabbing these terrified and exhausted animals, as is documented in undercover investigations made into production facilities.

And not only is time at a premium – so is space. Barns are filled with hundreds to thousands of animals at a time, so neglect is also common on large factory farms like Tyson’s.

Tyson Foods was created by John W. Tyson during the Great Depression in 1931. Tyson had moved to Springdale, Arkansas with his family hoping to find a profitable business venture and soon started delivering chickens to consumer markets in the Midwest.

When World War II struck, food was rationed, which put a damper on certain businesses, but chicken sales were not affected. Tyson started raising chicks and grinding feed for local farmers.

The company was founded in 1935 and initially focused on breeding meat chickens. Expanding early into other parts of the farming value chain, Tyson Feed and Hatchery, Inc was founded in 1947 and primarily sold baby chicks and animal feed, and transported chickens to the market.

Tyson Foods built its first processing plant in the 1950s and went public in the 1960s. Tragedy struck in the late 60s after the untimely death of John W. Tyson and his wife, Helen. The company was run by Tyson’s son, Don, and he was able to take Tyson Foods to new levels. With one CEO in between, in 2000, Don’s son was named the CEO of Tyson Foods Inc., and Tyson acquired IBP, Inc. making Tyson Foods the world’s largest processor and marketer of chicken, beef, and pork.

In 2014, Tyson Foods, Inc. acquired The Hillshire Brands Company, home of Jimmy Dean, Ball Park, State Fair, and Hillshire Farms. This massive investment contributed to Tyson’s portfolio reporting over $40 billion in annual sales.

Tyson Foods started as a small animal feed and chick operation but has grown into one of the largest chicken, pork, and beef producers in the world. Tyson Foods is a publicly traded company listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Like many traditional companies, Tyson has partly been a family affair. Since it’s founding by John W. Tyson, two other Tyson’s have held the position of CEO, and the current Chairman of the Board is John H. Tyson, John W. Tyson’s grandson.

Tyson’s Board of Directors consists of twelve individuals with various backgrounds, as well as thirteen enterprise leadership team members.

John W. Tyson, the founder, was CEO from 1935 until his death in 1967. His son, Don Tyson, served as the company’s CEO and chairman from 1967 to 1991. Leland Tollett was CEO from 1991 until 1998, when Don’s son, John H. Tyson, took over.

Tyson Foods encountered multiple changes of power from then until September 2018, when the current President and CEO, Noel White, took over.

Tyson Foods Inc. has around 800 institutional shareholders owning over 250 million shares valued at over $20 billion, out of today’s market capitalization of $29 billion.

The top owners of Tyson Foods Inc. include T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc., The Vanguard Group, Inc., BlackRock Fund Advisors, and SSgA Funds Management, Inc. These shares are collectively valued at over $7 billion. T. Rowe alone holds a stake of over $3 billion, representing nearly 13% of outstanding shares.

Tyson Foods Inc. also has a long list of mutual fund holders, with the top fund manager once again being T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc. Their value fund and equity income fund holdings are worth over $1.2 billion.

Tyson Foods acquired the meatpacking company IBP, Inc. in 2000, and in 2014, Tyson Foods, Inc. acquired The Hillshire Brands Company, home of Jimmy Dean, Ball Park, State Fair, and Hillshire Farm.

Since 1994, Tyson Foods has been the sole owner of Cobb-Vantress, Inc., which breeds, hatches, and sells live chicks to Tyson’s thousands of contract farmers, the so-called Tyson Family Farms, who are often also under contractual obligation to buy other resources like feed from the Tyson conglomerate.

The contract farmers are nominally independent, but for all practical purposes they are also under obligation to sell their chickens to Tyson. The conglomerate also finances contract farmers, effectively having them under financial control, too. The practice of contract farming has been widely criticized in books and documentary films alike.

Outside of human-grade meats, Tyson’s subsidiaries also consist of the dog treat companies Nudges, Top Chews, and True Chews.

Tyson Fresh Meats Inc. is a beef and pork-focused branch of Tyson Foods, whose brands include Chairman’s Reserve, Open Prairie Natural Meats, IBP Trusted Excellence, and Reuben.

Tyson Foods is an active spender in lobbying. According to the date from The Center for Responsive Politics, Tyson Foods had spent nearly $17 million on lobbying in the last ten years. Agriculture, taxes, transportation, and trade are the key issues where Tyson’s lobbying dollars are aimed. The Center for Media and Democracy reports that Tyson Foods, along with other “fresh meat” companies, is also a supporter of Center for Organizational Research and Education, previously known as The Center for Consumer Freedom, a lobbying group that campaigns against animal protection laws and against animal rights organizations, among other causes.

Tyson Foods has more than 100,000 employees spread around the U.S. and also works with around 9,000 independently contracted chicken growers. Tyson Fresh Meats employees around 41,000 people.

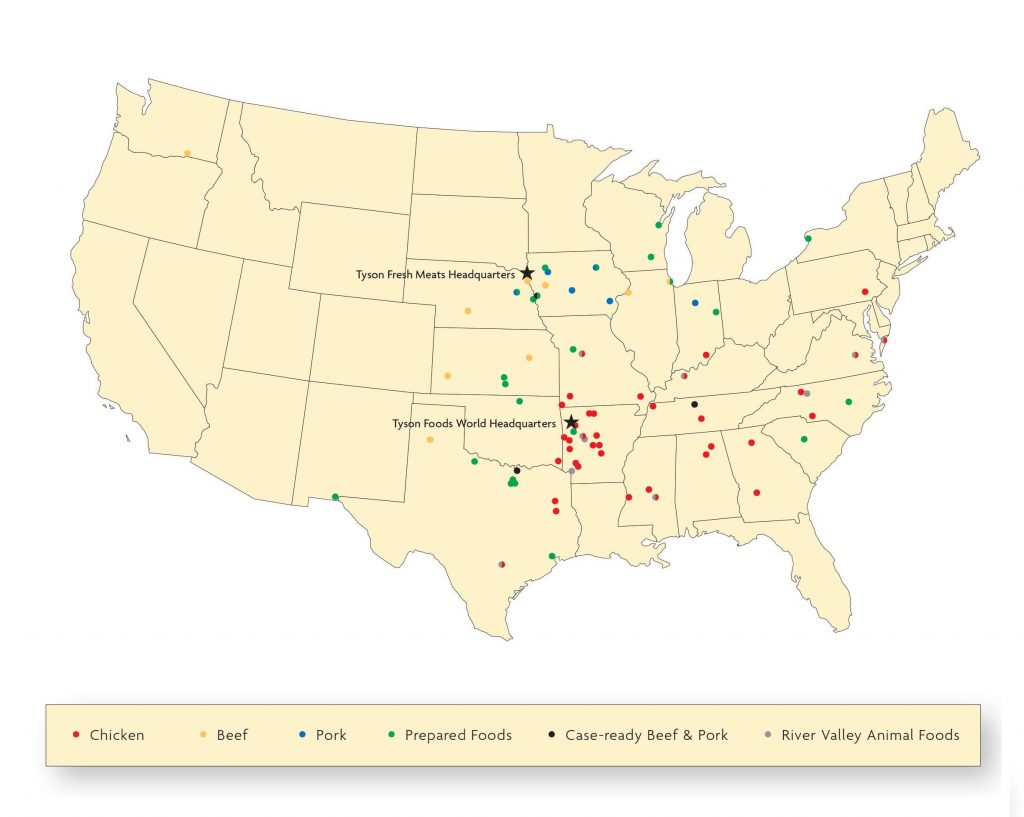

The map below demonstrates Tyson’s most prominent chicken, beef, and pork producing locations, not including their four international facilities.

Tyson Foods Inc.’s headquarters is located in Springdale, Arkansas, where John W. Tyson first broke ground with his chicken feed and transportation business back in the 1930s.

Tyson Fresh Meats Inc.’s headquarters is located in Dakota Dunes, South Dakota, the largest beef packer and second-largest pork processor in the U.S.

Tyson Foods slaughters approximately 37,000,000 chickens per week through fifty facilities, which means the daily total of birds killed each day equates to around 5.3 million.

These numbers mean that during the time you have been on this page, Tyson Foods has on average killed – and keeps on killing:

Chickens dominate the count, both for Tyson and the food system as a whole. Out of the 9 billion land animals killed for food in the U.S. each year, around 88% of them are chickens.

Tyson Foods is at the top of the food chain of meat producers around the world, so in order to keep up that pace, workers must raise, slaughter, and process animals rapidly.

And in order for that to happen, animals must be bred in large quantities, fattened quickly, and slaughtered in a constant cycle. The pace, scale, and pressure can easily lead to neglect and outright abuse, as has been documented.

An undercover investigation produced by Animal Outlook, formerly Compassion Over Killing, revealed cruelty throughout the supply chain of a Tyson supplier in Virginia.

The findings were disturbing, as chicks were bludgeoned, thrown, kicked, run over by machinery, and impaled by a metal spike.

Chickens were also found overstuffed and unable to move due to their unsustainably rapid growth. Meat chickens, usually known as broilers, have been selectively bred to produce more meat faster, which often results in the inability to function properly as actual animals. These birds grow so quickly that they are sent to slaughter at just 45 days old when the average lifespan of a backyard chicken is anywhere from 5 to 8 years or so.

When slaughtered, essentially while they are still in the baby stage of their lives, they weight about 5.5 lbs. To illustrate how unnatural that is compared to chicken growth in the 1950’s, that’s the same as if a year-old human baby weighted 93 lbs.

A PETA investigation of an Alabama Tyson location displays disturbing footage of live birds surviving the throat-cutting process whose heads were ripped off by workers as they pass on the conveyor belt. Workers also slam birds’ heads against machines, aggressively force them into shackles, and stack multiple birds into one set of shackles as if it were a game.

A PETA undercover investigator claims he witnessed severely burned yet conscious birds in the feather removal tank. The manager told him up to 40 birds could be scalded alive per shift without cause for concern.

One worker tells an undercover investigator that, “Yesterday, I ain’t gonna lie, man, I straight up broke one’s back… I hurt an innocent chicken because the other chickens made me mad.”

This type of cruelty is not specific to one processing plant. Tyson Farms, as well as their suppliers, have been the stage for such acts for years.

Eating any processed meats poses a health risk in and of itself, but when you add in the quick pace of continuous production, accidents are bound to happen – and Tyson is no stranger to recalls. Tyson claims to put public safety at the top of its priorities list, but if that were truly the case, these accidents should not be as frequent.

In 2019 alone, Tyson has already had major recalls of a variety of chicken products. Nuggets, strips, and chicken fritters are among the millions of pounds of products that have been removed from store shelves due to serious recalls. Rubber, metal, and plastic materials made their way from the production line to the plates of unsuspecting families around the United States.

In January of 2019, Tyson Foods recalled more than 36,000 pounds of chicken nuggets after consumers found pieces of rubber inside the bags.

Just a few months later in May of 2019, almost 12 million pounds of chicken strips were recalled due to possible contamination of metal shards.

Astoundingly, Tyson recalled almost 200,000 pounds of chicken products the following month in June of 2019 after complaints of hard plastic were found in school lunches.

Tyson has been involved in numerous lawsuits and paid out millions of dollars due to careless practices evoking environmental concerns.

Factory farms are a main contributor to resource depletion and the spillage of toxic chemicals into the environment. Tyson Foods processes millions of animals per year and their waste has to go somewhere.

In June of 2003, Tyson Foods admitted to illegally dumping its untreated wastewater from their processing plant near Sedalia, Missouri.

Investigations of the plant started in 1997, and two criminal search warrants were served in 1999. The company continued to illegally dump wastewater even after multiple warnings, two state court injunctions, administrative orders, and a federal search warrant.

Finally, in 2003, Tyson agreed to pay $7.5 million in fines to the federal government, the state of Missouri, and the Missouri Natural Resources Protection Fund.

In 2002, three residents of Western Kentucky, along with the environmental organization Sierra Club, filed a lawsuit concerning the discharge of dangerous quantities of ammonia from Tyson’s Western Kentucky factories.

Tyson settled the suit in January of 2005, agreeing to spend $500,000 to mitigate and monitor the dangerous ammonia levels.

In 2004, Tyson was among six poultry companies responsible for phosphorus seeping from its fertilizer into the drinking water supply of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Tyson had to pay a $7.3 million settlement fee to the city of Tulsa for the inconvenience and safety hazard.

On June 6, 2019, a Tyson Foods facility spilled around 800,000 gallons of wastewater into the Black Warrior River in Alabama.

An estimated 175,000 fish were killed in a nearby fishery due to low oxygen levels and E.coli contamination. The Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources believes it will take five years for the fish population to fully recover.

Dozens of local residents and business owners are suing Tyson for their carelessness. One woman was hospitalized after ingesting river water, and several businesses are losing revenue as a result of the spill.

Every year in the U.S., 9 billion chickens are slaughtered for human consumption, and almost 2 billion of those chickens are killed by Tyson Foods alone. The company is one of the largest meat producers in the world, slaughtering around 37 million chickens per week.

Aside from the health concerns of eating processed meats, Tyson products have been recalled for containing various foreign objects. Tyson has also been involved in multiple environmental scandals and is directly responsible for cruel treatment of animals as part of its high speed, high volume animal meat operation.

Animal cruelty does not exist exclusively on Tyson farms; whenever there is factory farming, abuse and neglect will be present.

Tyson’s strategy is to “sustainably feed the world,” with a commitment to “transparently advance [the] animal welfare experience.” But all undercover footage and whistleblower evidence prove that Tyson has a long way to go in improving animal welfare, sustainability, and a healthier environment.