Investigation

Oklahoma’s Loophole: How Tyson’s Water Use Goes Unchecked

Food•15 min read

Reported

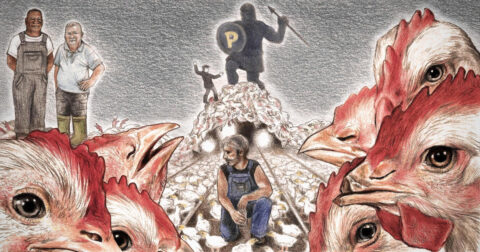

Through a series of exclusive interviews, our reporters offer key insights into the role chicken farmers are playing in the fight for a more equitable food system.

Words by Jennifer Mishler

In a civil antitrust lawsuit filed on July 25, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) alleges that three poultry producers—Cargill, Sanderson Farms, and Wayne Farms—suppressed pay for plant workers and deceived contract chicken farmers.

Using a “tournament system,” Sanderson Farms and Wayne Farms paid farmers based on their performance, a practice the DOJ says “pits chicken growers against each other to determine their compensation.” But contract chicken farmers, who raised more than 8 billion birds in 2020, were already operating at a disadvantage.

Over the past five years, the U.S. poultry industry has become infamous for its lack of competition. According to WATT PoultryUSA, 95 percent of chicken farms are controlled by 20 companies, and more than half of those farms are controlled by just four producers: Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Sanderson Farms, and Mountaire Farms. These mega-corporations oversee every stage of the production process—from the moment a chicken is born to the second they are slaughtered, processed, packaged, and shipped to consumers. The responsibility for their welfare, however, falls on farmers.

Even when farmers report violations, they are often ignored, penalized, and sometimes fired. In the fast-moving supply chains that have come to dominate the sector, one thing is clear: Farmers and animals are left to fend for themselves.

On July 8, 2020, Perdue chicken farmer Rudy Howell gave a group of journalists access to his facility in Fairmont, North Carolina, hoping that they would report what he believed to be violations of federal food safety laws. They found that, despite the company’s high welfare standards, some chickens could not survive 45 days on the farm.

Footage collected by We Animals Media showed baby birds scattered across the barn floor, sick and dying. The report was published by the Guardian and Sentient Media, and a few weeks later, Howell was fired.

The arguments for Howell’s dismissal are thin. He had previously disclosed his concerns, mainly over the rapid declines in animal welfare he witnessed on the farm, to representatives of his parent company, Perdue Farms. But they did nothing—at least until the media showed up.

Perdue claims that Howell breached their contract by inviting investigators into the chicken houses. But, according to court documents obtained by Sentient Media, “the Poultry Producer Agreement makes no reference to visitors.” The company also says that Howell violated biosecurity protocols, even though the personal protective equipment he received from Perdue was distributed to the journalists during their visit.

Howell has since filed a complaint against the poultry giant, part of his effort to ensure better protections for contract chicken farmers who face backlash from their companies after speaking out. The complaint alleged that Perdue violated the employee protection provisions of the Food Safety Modernization Act. It also details “unlawful retaliation” after Howell made protected disclosures regarding the company’s unsanitary conditions and threats to food safety.

Perdue has a reputation for misleading consumers about the welfare of its chickens. But Howell says the company is taking it a step further. He claims Perdue is lying to farmers about the amount of feed they’re receiving, forcing them to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on farm equipment they don’t need, and making other demands that hurt the farmers’ bottom line.

Every change Perdue makes to their chicken supply chain comes at the expense of farmers, Howell says. If the company was in $250,000 of debt, the farmers would pay for it, he says.

“Crap runs downhill, and it’s the people at the bottom who are gonna catch it,” says Howell.

Howell says most chicken farmers don’t know what they’re getting themselves into when they sign contracts with multi-billion-dollar meat companies like Perdue, but he does, and he doesn’t want to see anyone else sell their life away.

Craig Watts was 25 years old when he signed his first contract with Perdue, following in the footsteps of his parents who were crop farmers. He was drawn in by an “appealing” contract but would soon learn that working for the chicken company was not what he expected.

In 2014, Watts opened his farm to the animal protection organization Compassion in World Farming, allowing investigators to document the health of his chickens for the first time. The video revealed leg deformities and other crippling injuries common in factory-farmed birds.

But U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) records would later reveal that despite their “inhumane” treatment, the chicken produced at his farm was sold under the agency’s Process Verified program, which alongside other standards, assures that birds are “humanely raised.”

Misrepresentations like this are not contained to one farm or even one meat company. “We have to completely rethink our food system,” Watts says.

In 2016, poultry became the top-selling meat product in the world. This was due, in large part, to the development of new chicken breeds designed to grow faster and larger than ever before. Chicken farms are taking on a new look, too. Over the past 50 years, the average chicken farm has grown substantially—from 100,00 birds in 1972 to more than 350,000 today. But this expansion comes at the expense of both chickens, who struggle to walk under the weight of their unnaturally large bodies, and farmers, who struggle to keep pace with the accelerated rate of production and often fall into debt.

After more than two decades on the job and half a million dollars in debt, Watts decided to step away from the chicken farming industry and started growing mushrooms out of a renovated poultry shed. “It’s been a learning experience,” he says, one he is proud to tell his kids about.

A father of three, he first decided to become a chicken farmer because it offered him the chance to be at home with his family. But he wants a different life for his children. “They saw what I went through,” he says. “I think they’re smart enough not to choose that.”

There are others, though, who still want in. Watts has a word of caution for them.

“Do your research” before signing a contract with a big chicken company, he says. “Ideally, I would tell them not to sign it,” but because these farms are often located in poor communities, Watts knows that to survive, many have no choice but to sign.

Curt Covington is a commodities expert at AgAmerica, one of the largest non-bank agricultural lenders in the U.S. He says that while some farmers may feel forced to sign unfavorable contracts with poultry companies, many still see chicken farming as a promising economic opportunity. And for years, it was.

During the second half of the 20th century, chicken farms dramatically increased their productivity, utilizing bigger barns and faster growth rates to produce more chickens with fewer farmers. According to the USDA’s U.S. Agricultural Censuses, prior to 1950, eight out of every 10 U.S. farms raised chickens. By 1992, chicken farming had become a highly specialized, industrial practice, representing just five percent of U.S. farms. It had also ballooned in value, from $268 million to more than $9 billion.

The key to poultry farming’s early success was its relatively low cost of production. From 1960-2006, the price of chicken rose by 2.7 percent per year while the prices for all other foods rose by 4.2 percent per year, according to the Consumer Price Index. Researchers believe the resulting price difference may have led consumers to choose chicken over more expensive sources of protein.

The poultry industry has quadrupled its revenue over the past 40 years. But even good business comes with challenges. For chicken farmers, he says, one of the biggest challenges is understanding how larger economic forces like COVID-19 and inflation affect their farming operations.

“A lot of poultry farmers find themselves in situations where the economies of scale aren’t working for them like they used to,” he says.

Young farmers, in particular, often bear the brunt of these changes. Covington says they are often forced to operate facilities that are not as technologically advanced as they should be. The new techniques young farmers learn in ag school won’t help them there. They learn quickly that raising chickens on an old poultry farm is a lot like driving a car you bought in 2005. It just doesn’t run as well as it used to.

Covington says at that point, farmers have to make a decision: take on more debt, buy new equipment, and grow the business, or downsize and focus on serving smaller markets.

Most farmers choose the former. “If you don’t grow, you die,” says Covington.

When poultry companies mistreat farmers, Amanda Hitt is one of the first lines of defense. She says most people do not understand the bind farmers are in.

“If you graduated from Prestage Poultry School that preaches industrial animal agriculture, and your lender says, ‘I’m going to give you one million dollars, and you’re going to grow chickens for my company,’ and the only thing you’ve got going on in your small town is a Walmart and a Dollar General—you’d be out of your mind not to go for that,” says Hitt.

Corporations have a long history of extraction in rural communities, leaving hundreds of thousands of small business owners with nothing but land to their names. So when a poultry company approaches an unemployed farmer and offers them a government-backed loan to open a new chicken farm, they take it.

“They’re not stupidly entering into contracts that everybody knows are bad,” she says. “They’re being coerced by their circumstances and the lack of opportunity.”

Without federal support, Hitt says farmers would not be entering into these contracts. But as soon as they do, they open the door for the Perdues and Sandersons of the world to profit from their financial risks.

“This system was created to basically steal from people,” she says. “It’s the Wild West out there, and someone needs to police it.”