Investigation

Oklahoma’s Loophole: How Tyson’s Water Use Goes Unchecked

Food•15 min read

Explainer

The poultry industry uses the term "broiler chickens" to describe birds farmed for meat. But where exactly does the term come from?

Words by Grace Hussain

Modern broiler chickens are birds farmed for meat on factory farms — the result of decades of intensive breeding efforts controlled mostly by just two companies, Tyson Foods and a poultry breeding company called Aviagen. Breeding for specific traits has resulted in birds who eat very little but grow very quickly, which causes chickens to experience pain and illness.

Broiler chickens are birds raised specifically for their meat. This particular type of livestock makes up the vast majority of chicken eaten worldwide. Through intensive breeding, two dominant strains have surfaced, Cobb and Ross. Tyson Foods owns Cobb-Vantress, which is behind the Cobb strain of broiler chickens. Cobb-Vantress sells birds to over 120 countries and recently Cobb chickens were the first broiler chicken imported into Kyrgyzstan. Aviagen owns the Ross strain of chickens, which is the most popular strain of broiler birds in the world. The company has distributors that make Ross chickens available globally.

The name “broiler chicken” originally comes from a preparation and cooking method in which young birds of 5 to 6 weeks old are split open and broiled. Chickens of other ages were similarly named according to cooking methods, including “fryers” or “roasters.” The USDA still classifies poultry using such terms, though they have been updated to reflect faster growing times. The vast majority of birds sold are broiler chickens, and this has also become a generic term for birds farmed for meat.

There are no genetically modified chickens available for sale anywhere — at least not in the way the term is typically used. Genetically Modified Organism — often called by its initialism GMO — is not a scientific definition. Yet most people use the term GMO in place of the more accurate scientific terminology “transgenic,” a breeding method where scientists genetically boost the traits of a living organism with the addition of DNA. Chickens on the market today are bred to boost many of their natural traits, but animal scientists do this using conventional animal breeding methods.

Over the last several decades, numerous generations of chickens have been bred to maximize two traits: growth and feed conversion efficiency. Raising birds that grow very quickly while eating a minimal amount of food translates into larger profit margins. Modern chicken strains continue to push the boundaries of production.

For example, at 42 days old, when the birds are likely to be sent to the slaughterhouse, the average Cobb500 broiler chicken will be over 7 pounds with an average daily weight gain of a quarter of a pound, and yet will only be consuming half a pound of feed a day. In 1925, before birds started being bred so intensively, it took 112 days for a chicken to reach slaughter weight. When they were killed, they weighed only 2.5 pounds and had consumed about 4.7 pounds of feed for each pound of weight.

The genetic changes involved in this transformation have not been without consequences, as birds suffer immensely due to their swift growth rate. Modern broiler chickens frequently suffer from heart issues, leg issues such as bone infections and even premature death.

Broiler chickens have been bred to grow very quickly while eating only a small amount of feed, making them ideal for slaughtering for meat. Laying hens, on the other hand, have been bred to produce an extremely high number of eggs. Per the United Egg Producers, an industry organization, the average commercial laying hen laid just under 300 eggs in 2020. Just 20 years prior in 2000, the average hen was laying only 264 eggs per year.

Most female broiler chickens are slaughtered before they are old enough to lay eggs. However, some birds are kept as parent birds who do lay eggs. These birds often have their feed restricted to prevent the obesity-related issues of broiler breeds. Parent birds show behaviors suggesting that they are in a constant state of hunger, including feather pecking and overdrinking, which are in themselves associated with a number of welfare issues.

The life of a broiler chicken usually involves four major facilities: a broiler breeder farm, a hatchery, a factory farm, and a slaughterhouse.

The first step in raising broiler chickens is to order pullets, or young female chickens. Once they are old enough, these chickens will be bred to produce eggs which will hatch into flocks of broiler birds. On factory farms, eggs are likely taken from the mother hens and placed into artificial incubators where they will remain until they hatch.

Artificial insemination is not widely used on most factory farms, as natural mating tends to provide ample fertilized eggs to maintain flock cycles. However, artificial insemination is commonly used by geneticists in labs seeking to further maximize the productivity of broiler chickens.

Once eggs are laid, they are collected and transported to hatcheries where they are stored in incubators that keep them warm until they are ready to hatch. In 2021, 9.88 billion broiler chicken chicks were hatched in the United States.

Once the eggs have hatched, the baby birds are shipped to factory farms where they spend the next six to seven weeks feeding and growing.

The final episode in a broiler chicken’s life is when they are shipped to a slaughterhouse and killed. Worldwide, this is the fate of more than 70 billion broiler chickens annually.

The amount of time it takes to raise a broiler chicken is determined by how fast one can get the chicken to the desired market weight. This period has become drastically shorter over the course of the last 100 years.

Today the average chicken raised for meat is slaughtered between 6 and 7 weeks of age. At this age, the chicken is likely to already be over 6 pounds.

There are numerous problems associated with broiler chickens ranging from the ways that their welfare is compromised in factory farms to the health issues they experience as a result of their breeding, and the impact of raising broiler chickens on the environment.

Broiler chickens are subjected to a number of factors that negatively impact their overall welfare.

Debeaking means removing the tip of the beak and is done to curb behaviors such as feather pecking. Birds raised for meat are debeaked at a young age.

Due to the ongoing outbreak of avian flu, millions of chicks are being culled, or killed, before they are sent to slaughter. Not all of these birds are ill themselves, rather they are culled because of feared exposure to the disease.

Catching and transporting chickens leads to a large amount of stress for the birds. This is in large part due to being stuffed into one crate with several other birds.

Overcrowding presents a serious problem for broiler chickens. High stocking densities result in behaviors such as increased panting and dirty feathers.

At the time of slaughter, chickens are already stressed from being transported and are then subjected to handling. Upon their arrival they are often handled extremely roughly due to high slaughter line speeds.

Mortality can occur due to handling, disease or genetics. The specific rates of pre-slaughter mortality vary based on numerous factors. One study based at an Italian abattoir and published in the Italian Journal of Food Safety in 2018 found that up to 0.5 percent of birds were dying in transport and handling.

Broiler birds suffer from an array of different health issues, in large part due to their swift growth.

Their growth rate places pressure on their hearts, which are not able to meet their bodies’ demand for oxygen. This leads to heart conditions.

Ammonia resulting from chicken droppings can cause abnormal eye conditions, including severe lesions if ammonia levels are high enough.

A broiler chicken’s bones are often unable to support their swift growth. This often leads to lameness.

Though footpad lesions represent an issue for all broiler birds, the situation is most dire for breeder birds, who are subjected to extra wet bedding due to their excessive drinking.

Estimates suggest that every day, each broiler chicken produces up to half a gram of ammonia. This ammonia can increase the severity of algal blooms and dead zones in nearby waterways.

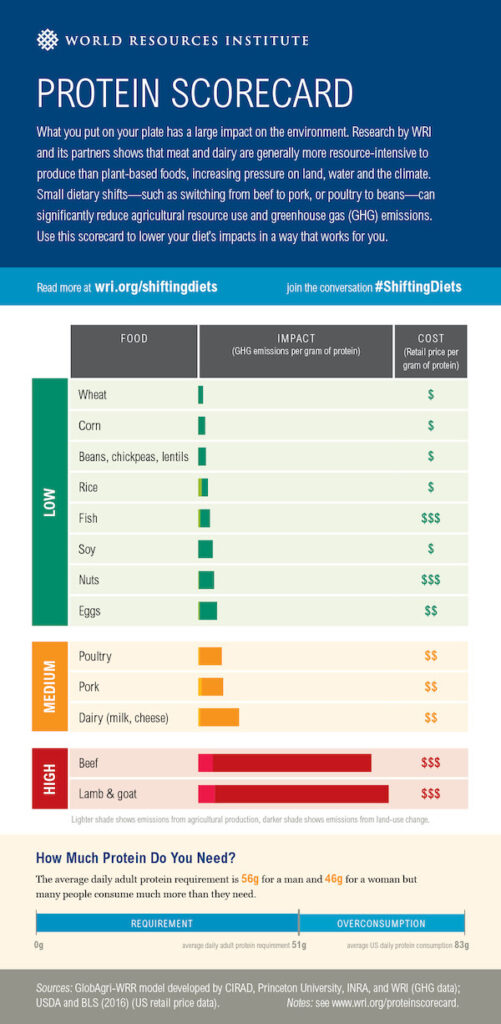

The average broiler house is responsible for 847 tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases per year. The largest contributions to greenhouse gas emissions on a broiler farm come from the use of propane and diesel. Greenhouse gas emissions from chicken are much lower than beef or dairy, yet higher than plant-based alternatives.

Perhaps one of the most prominent examples of the impact of pollution from chicken farms on bodies of water is that of the Chesapeake Bay. Pollution from chicken farms has led to algal blooms and dead zones in the bay.

The modern broiler chicken is the result of years of selective breeding to create fast-growing chickens. Chickens raised on factory farms are subjected to overcrowding and, more recently, mass culling due to outbreaks of disease. One effective way to reduce animal suffering is to shift to a plant-rich diet. Other actions you might take include signing petitions or volunteering at a local farm sanctuary. You can explore these suggestions and more by visiting our take action page.

An earlier version of this story was written by Jennifer Mishler.