Investigation

What Does a Small Town Do When the Water Is Undrinkable?

Climate•8 min read

Reported

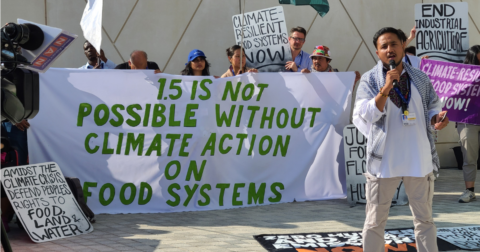

Climate negotiators have started to tackle food systems reform, but hard commitments are still largely missing.

Words by Lyse Mauvais

COP28 ended on December 13 under the glittering towers of Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), after two weeks of strenuous negotiations. The COP (which stands for Conference of Parties) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is the global forum where climate issues are discussed. The number of participants to the talks have skyrocketed over time, peaking this year at 103,000 people, including government delegations, trade groups, climate activists and journalists.

The aim of the talks is for countries to agree together on an action plan to avert the most catastrophic impacts of global warming by keeping average temperatures from rising by more than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, in line with the 2015 Paris Agreement. These efforts have long crystalized around fossil fuels, a leading cause of greenhouse gas emissions, but they also increasingly take into account food systems, which are responsible for around one third of current emissions.

“This year, significantly more attention has been paid to the impact of our food systems — not just on the environment but also on food security, human health, people’s livelihoods and on animals,” Perran Harvey, Senior Global Policy Lead at Upfield, tells Sentient Media.

In response, a flurry of pledges, declarations and initiatives were launched during the talk. But was this enough to impact the way our food is produced, often in highly polluting ways?

To make sense of what happened at COP28, and how it’s likely to impact the future of food, here’s our wrap-up of the negotiations, taking you through the four key takeaways for food systems of the world’s biggest climate event.

1. Countries recognized that food systems are under threat, and committed to cut emissions from agriculture and the livestock industry

Since it came out on December 2, over 150 countries have signed on to the UAE Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action, in which governments recognize the need to help farmers adapt to climate change and pledge to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. The list of countries that signed, which includes the United States, are responsible for 73 percent of the food we eat and 78 percent of total emissions from food systems. On December 10, a special taskforce was created to help governments implement these commitments by setting emissions reductions targets in this long-overlooked sector.

“[This declaration] is a major signal from COP28 that nations must act on food and agriculture if we are to meet our global climate (and biodiversity) goals,” Edward Davey, Partnerships Director, Food and Land Use Coalition at the World Resources Institute, tells Sentient Media. “The Declaration is the first of its kind on food; and exceeds past declarations in terms of the number of endorsing nations.”

2. Left off the menu: Some pledges were “ambitious,” but others left key terms like “regenerative” undefined

Also on December 10, which was dedicated to Food and Agriculture, delegates launched the Alliance of Champions for Food Systems Transformation. It’s presented as a coalition of “ambitious” states that want to lead the way in transforming their respective food systems. The alliance currently includes Cambodia, Norway, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Brazil, the largest exporter of beef worldwide.

But beyond these “a la carte” commitments, whose results are yet to be seen, COP28 also managed to drizzle some food systems language into the main course: the Global Stocktake (GST), widely considered the most important text adopted this year at COP.

The GST is meant to assess the progress made so far to achieve climate goals, and issue recommendations to governments. These include a nudge to governments to increase the resilience of food systems to climate change, and to increase “sustainable and regenerative production.”

The recommendations suggest a shift away from highly polluting forms of agriculture and industrial-scale cattle-ranching. For many observers, the language was a breakthrough, but others hoped for a more ambitious text — one that would actually define what “sustainable” food systems and “regenerative” farming practices actually mean.

3. COP28 hosted hundreds of events on food systems — and many of them were organized by the meat and dairy lobby

COPs are a powerful platform to campaign and connect, which explains why they’ve ballooned to tens of thousands of attendees in recent years. Among this years’ participants were hundreds of food systems activists, nutrition nerds, interest groups and industry representatives who all wanted a seat at the table.

Several hundred accrued on the civil society side from organizations advocating for more climate-conscious food production — such as ProVeg, the Good Food Institute and Mercy for Animals. Their interest materialized in at least 700 official and unofficial side events held on the sidelines of COP, mostly in “pavilions” rented by coalitions of organization to showcase their work.

The buzzing heart of this beehive was undoubtedly the Food Systems Hub, a two-floor building dedicated to hosting events about nutrition and agriculture. Filled to the brim with participants fluttering between various panels, the hub notably hosted three pavilions sponsored by various coalitions, and dedicated to raising awareness about the climate-food systems connection: Food4Climate, Food Systems and Food & Agriculture.

At the same time, an unquantified number of industry representatives flocked to the talks, including prominent meat and dairy trade lobbies like the Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef, Meat and Livestock Australia and the European Dairy Federation. Unlike civil society groups, who are generally registered as “observers” and can’t enter negotiation rooms, many of these lobbyists came on the back of official delegations, which granted them significantly more access to the talks.

These heavyweights of industrial agriculture, which include the world’s largest meat company JBS and the all-powerful pesticide industry’s main trade group, CropLife, rallied around a common narrative that highlighted the benefits of industrial agriculture and cattle ranching. They did this by running panel discussions on “nutritious animal-based food” and “sustainable beef,” many of them hosted by the industry-friendly Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA)’s pavilion.

4. Two important reports came out on food and climate, calling governments to action

Despite the shortcomings, two crucial reports came out at COP28 that made a clear case against maintaining our current food production practices.

The first report, released by UN Environment on December 8 and titled “What’s Cooking,” bluntly recognizes “the need to change the way we produce and consume the food we eat.” Assessing the nutritional and environmental potential of “novel alternatives to conventional animal source food,” the report makes a case for alternative sources of protein, which will be key to reducing our reliance on livestock, a highly polluting industry that takes up 26 percent of the planet’s ice-free land for grazing, and 33 percent of cropland for to grow feed for animals, like soy and corn.

The second is the much-awaited first chapter (out of three) of the UN Food and Agriculture (FAO) Global Roadmap on feeding the planet sustainably, which warns that wealthy industrialized countries like the U.S. will have to cut back on how much meat and dairy we eat, while sub-Saharan nations should strive to make agriculture and livestock more productive.

The report was generally hailed by food systems activists for putting the science on the table and calling out the need for more sustainable farming. But it also raised many concerns, especially “the roadmap’s omission of the impacts of industrial animal agriculture, and the need to reduce and ultimately phase out our reliance upon industrial animal farming, a key driver of the climate, nature and health crises,” 21 civil society organizations wrote in a joint response to the FAO roadmap.

“While the roadmap makes commendable strides in important areas for food security, it also exhibits notable gaps,” signatories said, warning that “the suggestion to use livestock methane for biogas risks creating perverse incentives to intensify and expand animal agriculture, contradicting the need for a holistic food systems transformation.”

The road to climate-conscious agriculture is still long and laden with obstacles. But COP28 has at least set a few pebbles rolling, hopefully in the right direction. “The most impactful and effective activity happens in the time between the COPs,” Bruce Friedrich, CEO of the Good Food Institute, tells Sentient Media. “What happened at this COP gives us a really powerful lever to pull in our discussions with governments about the importance of food systems generally, and alternative proteins specifically.”

“What we really need now are concrete plans from signatories that actually spark the transformational shift towards plant-rich, balanced and sustainable diets we desperately need to make a difference,” Harvey says. “In our view, not enough progress was made at this year’s conference to legitimise COP28 as the ‘food COP’, and we still have a way to go to addressing the harmful aspects of our global food systems. However, now food is on the menu, it will continue to have a seat at future COPs where policymakers can incorporate all solutions at our disposal.”