Fact Check

Fact-Checking Claims Made About Oklahoma’s Lawsuit Against Tyson Foods

Food•5 min read

Solutions

Policies that target ultra-processed foods could end up being bad for both the plant-based industry and the planet.

Words by Grace Hussain

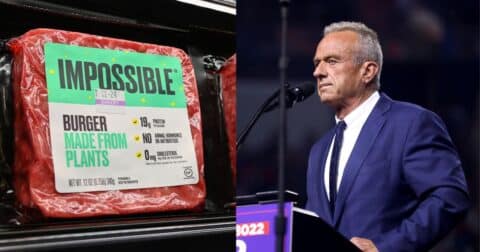

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s confirmation as Director of Health and Human Services — the government department that oversees the Food and Drug Administration and the Center for Disease Control among others — could be another damper for the plant-based food market. Through his “Make America Healthy Again” campaign, Kennedy has repeatedly argued that processed foods are poisoning the country, a stance he maintained throughout his confirmation hearings. And because processed foods aren’t well defined, any efforts by RFK to restrict ultra-processed foods could end up inadvertently discouraging U.S. consumers from eating plant-based foods. That would be bad news for the already-struggling plant-based industry, but also for climate change and the environment.

Though he did not support an all-out ban on processed foods during his confirmation hearing, Kennedy expressed his support for restricting school purchasing and limiting SNAP beneficiaries’ ability to purchase processed foods. While both SNAP and federal school purchases are managed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and thus would be outside of Kennedy’s direct control, the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services both work closely on food policy.

Now that he’s approved, Kennedy could push for a range of policies for reducing the country’s consumption of processed foods, including the FDA’s labeling requirements.

“Warning labels and taxes tend to change people’s behavior. So if you put a warning label on a product, people, on average, are a little bit less likely to buy that product. If you tax a product, people are a little bit less likely to buy it. It’s because it’s a little bit more expensive, so I would expect that those policies, if implemented, would reduce how much we eat those products,” Anna Grummon, who runs the Stanford Food Policy Lab, tells Sentient.

One of the factors that makes legislating processed foods difficult is the fact that not all processed foods are created equal. Some processed foods, such as sugary beverages like soda, have been linked to various health issues including diabetes and obesity. But that’s not the case for all processed foods, including plant-based meats.

The expansive category that is “processed foods” is why some policymakers and activists zeroed in on a new label: ultra-processed foods. But here too, there’s no single definition of what exactly constitutes an ultra-processed food. “That’s a challenge for making policy around ultra-processed foods,” says Grummon. “We have to have a definition we agree on, and that can be implemented by policymakers and by companies.”

Currently, the most prominent definition comes from the NOVA Food Classification System, which was proposed by researchers at the University of São Paulo. Under the system, ultra-processed foods are combinations of ingredients that are not whole foods themselves, or are “synthesized in laboratories.”

Another definition, appearing on the conservative organization Center for Renewing America’s website, notes a few factors in its definition of ultra-processed foods, including “packaged foods containing added preservatives,” and “manufactured ingredients…that extend the shelf-life of a product, enhance the taste of the product, and often result in habit-forming cravings…” (The founder of the organization was part of the first Trump Administration, and previously signaled his intent to defund the EPA, while also pushing transphobic rhetoric.)

The specific definition RFK Jr. prefers, and which would likely be replicated by the FDA, remains unclear. Regardless of the specifics of the definition, it’s unlikely to cleanly identify the least healthy foods, simply because all ultra-processed foods are not the same.

Some policies have addressed this problem by regulating nutrients, rather than the level of processing. For example, in Chile, products high in calories, sodium, sugar or saturated fat are required to have warning labels on the front of their packaging, and can’t be sold or served in schools. The approach has significantly cut how often those foods are purchased, though it doesn’t seem to have curbed obesity rates. In fact, the BBC reports obesity has increased among school children slightly since 2016 (though this may be attributable to an increase in sedentary lifestyles during COVID-19).

Policies focused on nutrient content “gets at ultra-processed foods indirectly,” says Grummon. The FDA is currently considering a rule that would require most foods to sport front-of-package nutrient labeling, ultra-processed or not.

Warning labels on ultra-processed foods sound like a good idea, but when it comes to plant-based meat, these labels could indirectly lead to negative environmental and public health impacts if consumers were to cut back on their plant-based eating habits as a result. Potential taxes that increase the cost of ultra-processed plant-based meats, like Impossible and Beyond products, are also likely to reduce the amount of those products consumers purchase, says Grummon.

“A key question is what do people switch to? Do they switch back to beef? Or do they switch to something else?,” she says. “That’s really important for understanding whether those policies would be good or bad for public health or good or bad for carbon footprint. I think if people switch back to beef, that’s not going to be good for carbon emissions, because, of course, beef has a much higher carbon footprint than Beyond and Impossible products.”

The average person in the United States already eats far more meat than the global average. For that reason and because of beef’s massive greenhouse gas emissions impact, climate research groups like the World Resources Institute include the recommendation that U.S. (and other global north) consumers eat less beef as part of their climate action plan for food-related emissions.

When researchers compare beef to plant-based alternatives, the alternatives consistently rank better, using less water and land and emitting far fewer greenhouse gasses. Other types of meat — like poultry and pork — are more moderate for greenhouse gas emissions, yet both are associated with poor animal welfare and polluting the air and water of communities that live near factory farms.

Even when looking at personal health, plant-based alternatives tend to perform as well as or slightly better than meat. Despite being categorized as ultra-processed, plant-based alternatives tend to be a little lower in fat and calories, and sometimes have more fiber than meat. On the other hand, meat tends to have less sugar and more protein per serving, and of course, individual products do vary.

If policies aimed at rolling back consumption of ultra-processed foods are enacted, many plant-based alternatives will likely be impacted, given that they’d be considered ultra-processed under the most prominent definition. “You can imagine some things being bad for sustainability, like people might eat fewer meat mimic[king] products, like Beyond and Impossible, because those are ultra-processed,” says Grummon.

A representative of The Plant Based Foods Association declined to comment for this article, stating, “given the potential regulatory outcomes are still unknown, we’d prefer not to comment at this time.”

It is possible that new policies targeting ultra-processed foods could persuade consumers to opt for more legumes over plant-based burgers or conventional meat. But given how often most U.S. consumers regularly eat lentils these days, it seems unlikely.

A new food labeling scheme could also make no difference at all. One study found that Swiss consumers already view meat substitutes as processed, regardless of the form they take; so it’s also a possibility that consumers willing to purchase plant-based alternatives won’t be swayed by new policies.

Ultimately, what policies RFK and the Trump Administration might pursue on processed and ultra-processed foods remain hard to predict, Grummon says. But many plant-based products are categorized as ultra-processed under any definition. Even if plant-based foods aren’t a particular target of policies aimed at sugary beverages or candy bars, regulatory language that focuses on the processing — instead of nutrient content — would likely end up including plant-based alternatives. These sorts of policies then could spell more trouble ahead, both for the plant-based market and the planet.

Update: This article was updated to reflect Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s confirmation Thursday.