Investigation

Oklahoma’s Loophole: How Tyson’s Water Use Goes Unchecked

Food•15 min read

Explainer

An estimated 121 million pigs are slaughtered every year in the United States, and one pork producer is responsible for over 15 million of those deaths.

Words by Taylor Meek

China, Thailand, and Brazil join the US in most pigs slaughtered, bringing the collective total to hundreds of millions each year.

Despite the fact that pigs are sensitive, intelligent, and cognitively complex animals, they are abused and slaughtered in horrific ways every day because people “just can’t live without bacon.”

Smithfield Foods raises and slaughters millions of innocent beings every year because profit trumps mercy in the business of factory farming.

Efficiency and speed within the production line are more important than the health and well-being of the animals bred specifically for human consumption. Faster production times often lead to unnecessary animal abuse, unsuccessful stunning before slaughter, and even safety risks for employees.

Smithfield Foods is a pig producer based out of Smithfield, Virginia, where millions of pigs are slaughtered every year.

Smithfield prides itself on raising “responsible, sustainable” pork products, but has been the focus of controversy since an undercover investigation by The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) unveiled immense cruelty inside its facilities in 2010.

Pigs were beaten, confined, and stressed, unlike what their promotional advertisement displayed just two months after the investigation.

The Smithfield Packaging Company was started in the 1930s by Joseph W. Luter and his son Joseph W. Luter Jr.

According to Joseph W. Luter III, his father and grandfather would buy 15 pig carcasses per day at the beginning of their endeavor. They’d sell the chopped up pieces to small businesses in Norfolk and gradually grew from there. In 1946, they opened up a processing plant on Highway 10 where they were slaughtering 3,500 hogs per day. Ten years later, their company had grown to 650 employees.

While they did face financial issues early on, Smithfield Foods has been a major player in the meat industry for decades.

When Joseph W. Luter Jr. passed away in 1962, his son, Luter III, stepped in to run the operation. He remained as CEO until 2006. In 2008, Luter IV joined as an executive vice president and stayed until 2013 when Smithfield Foods was bought by the WH Group of China, formerly known as the Shuanghui Group.

In 2013, the WH Group of China, the world’s largest pork producer, bought Smithfield Foods.

As millions of Chinese people started entering the middle class with the economic boom over the past decade, the demand for meat skyrocketed.

In the chart below, you can see the substantial growth per capita when it comes to meat consumption in China.

Pork is the most popular meat in China, so it wasn’t a big surprise when Shuanghui International bought Smithfield Foods for $4.7 billion in cash.

Shuangui, now the WH Group, was the largest pork producer in China before buying Smithfield Foods. Now, the WH Group is the largest pork producer in the world with a reported revenue of $22.38 billion in 2017.

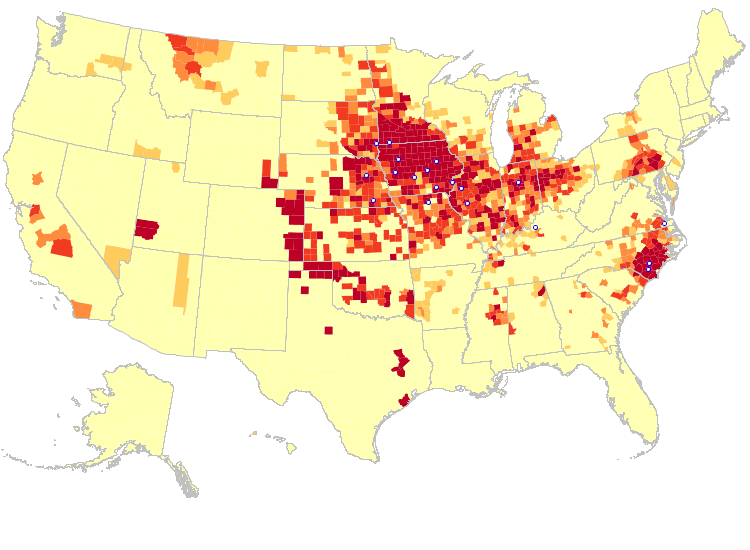

Smithfield Foods has offices, plants, and distribution centers around the world. Though heavily based in North America, there are pig producers and processing plants in South America and Europe as well.

Pork processing plants are divided by the products they provide, so one plant might specialize in pork rinds, while another produces pizza toppings like pepperoni or sausage.

The original Smithfield Foods is based in Smithfield, VA, but Smithfield now owns brands including Smithfield®, Nathan’s Famous®, Farmland®, Farmer John®, John Morrell®, Cook’s®, Curly’s®, Healthy Ones®, and Krakus®.

They are also owners of Eckrich®, Armour®, Kretschmar®, Gwaltney®, Carando®, Margherita®, Morliny®, and Berlinki®.

Smithfield Foods is the reigning “champ” in regard to raising and slaughtering the most pigs in the United States.

Now owned by the WH Group, the largest pork producer in the world, Smithfield has the funding and resources to crank out even more pig products in the United States and in other countries.

Since Smithfield slaughters around one million pigs per year, you would imagine Virginia to be a top-performing state in pork production.

Surprisingly, Virginia doesn’t even make the top 10 list. Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and North Carolina are the top producers of pork products, raking in BILLIONS of dollars each year.

Virginia is actually number 20 on the list of state rankings for pig inventory. As mentioned, North Carolina did appear high on the list, and that is partially because of Smithfield’s Tar Heel, NC plant, which has been crowned the largest pork packing plant in the world.

Smithfield Foods raised and slaughtered 15.6 million pigs in 2016.

The Tar Heel, North Carolina packaging plant has the capacity to slaughter 36,000 pigs per day. Smithfield’s Gwaltney plant in Smithfield, Virginia can process over 10,000 pigs per day.

The Smithfield-owned John Morrell® plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota can slaughter around 20,000 pigs on any given day.

The gestation period of a pig is almost four months long, and gilts, young female pigs, are bred at 170 to 220 days old.

Once they deliver their first litter of piglets, gilts are considered sows. For three weeks, sows are often kept in crates for the farrowing process. This is when piglets are nursed while their mother is kept behind bars and is unable to move properly.

Smithfield made a public announcement in 2007 to phase out the use of gestation crates for sows, which induce stress, physical pain, and mental anguish.

Though Smithfield has made an effort to phase out gestation crates, animals are still kept in undesirable quarters.

Once piglets are weaned off their mothers, they are kept in a separate barn for 6 to 8 weeks where they are fed a diet meant to fatten them up quickly.

In the “finishing” stage, pigs are crammed into metal trucks and transported long distances to the processing plant where they will be slaughtered.

These metal trucks can get to sweltering temperatures inside, and since pigs lack sweat glands and are denied access to water, it is an extremely unpleasant ride.

When traveling hundreds of miles with a truckload of live animals, accidents tend to happen. Below are some statistics from Smithfield’s transportation operations from 2013 to 2017. This does not account for any outside-sourced transportation loads.

In recent years, the number of fatalities has grown. Trucks often overturn, spilling live pigs onto highways where they run the risk of injury and death.

Once the pigs make it to the processing plant, they are fed copious amounts of corn until they are around 280 lb, which is considered “market weight.” Pigs are slaughtered at only six months old when the standard lifespan of a commercial pig is around 20 years.

According to the Food Safety and Inspection Services branch of the Department of Agriculture, there are multiple options to choose from when slaughtering animals.

Slaughterhouses may use carbon dioxide gas to suffocate pigs. They can also use a captive bolt or an electrical current that stuns them. Another option is a gunshot to the head.

Though these might seem like “humane” methods, frustration from handling a squealing, frantic animal coupled with quick slaughter expectations makes the slaughtering process a prime candidate for abuse.

Often times animals will live through the carbon dioxide poisoning or the electrical currents and be fully aware of the throat-slitting and/or boiling process that follows.

In 2018, the USDA proposed a plan, the “Modernization of Swine Slaughter Inspection,” that would increase slaughter speeds and decrease the amount of federal inspectors required within.

This ruling would give more power to the slaughterhouse workers with less supervision, meaning more opportunities for abuse, neglect, and ineffective slaughtering techniques. Not to mention a higher risk of injury for employees.

To the USDA, farm owners, and other agricultural leaders, pigs are just a product. They are not considered living, breathing, intelligent individuals.

When Hurricane Florence hit in 2018, farmers left their pigs and chickens behind. Since there are hundreds, even thousands packed into sheds at a time, it would be virtually impossible to release them all from these confines in time.

An estimated 3.4 million chickens and around 5,500 hogs were found dead on industrialized farms in North Carolina, many of which are contracted with Smithfield Foods.

Millions of animals drowned because they are merely considered as property. Their deaths were just the cost of doing business.

Undercover investigators witness horrific, life-changing, stomach-wrenching operations in order to bring footage of cruelty to the public’s eye. They endure physical, psychological, and emotional pain so that animals may one day not have to.

When animals are sick or injured inside factory farms, they are normally overlooked, thrown away, or killed. A sick piglet, for instance, is of no use to the farm since it is no longer deemed profitable.

In 2017, however, animal rights activists associated with the organization Direct Action Everywhere were hunted down by FBI agents regarding two missing piglets, Lucy and Ethel.

The piglets were surrounded by rotting carcasses and suffering greatly inside Circle Four Farm, owned by Smithfield Foods. “One was swollen and barely able to stand; the other had been trampled and was covered in blood,” said Wayne Hsiung of DxE.

When activists removed the piglets from their stressful, unsanitary environments and brought them to a rehabilitation facility, all hell broke loose. FBI agents barged into two farm animal rehabilitation centers, Ching Farm Rescue in Riverton, Utah, and Luvin Arms in Erie, Colorado.

The agents demanded DNA samples from any pigs that resembled Lucy and Ethel. A member of Luvin Arms recalls, “To obtain the DNA samples, the state veterinarians accompanying the FBI used a snare to pressurize the piglet’s snout, thus immobilizing her in pain and fear, and then cut off close to two inches of the piglet’s ear. The piglet’s pain was so severe, and her screams so piercing, that the sanctuary’s staff members screamed and cried. Even the FBI agents were so sufficiently disturbed by the resulting trauma, that they directed the veterinarians not to subject the second piglet to the procedure.”

An innocent piglet that had nothing to do with Smithfield Foods was forced to give up a piece of themselves just to prove they were not a match.

Some volunteers were even followed home by FBI agents and questioned about the missing piglets. It is also believed that FBI agents monitored the activists’ communications, as the names “Lucy and Ethel” were used internally as code-names, yet the public names of these piglets were “Lizzie and Lily.”

As mentioned, the loss of two sick piglets within any factory farm is merely just a mess to clean up. In this case, though, this rescue was the start of an unveiling process. Factory farms try to keep their industry secrets hidden for a reason.

Farmers know that people will not purchase their products if they see how they were produced.

A New York Times article highlighted photos from the rescue mission, which initiated the search warrant of the rehabilitation centers the following month. As more people are gaining access to the hidden horrors within the meat industries, demand falls and activism rises.

An undercover investigator from HSUS captured shocking footage inside a subsidiary of Smithfield Foods in 2010.

Just a few months after this horrific cruelty was captured, Smithfield released a promotional video highlighting how responsible, compassionate, and efficient they were. Their video was titled, “Taking the Mystery Out of Pork Production at Smithfield Foods.”

The biggest mystery here is how they magically remedied all of their animal welfare violations, inhumane procedures, and overall cruelty.

Smithfield Foods prides themselves on providing “good food, responsibly.” Unfortunately, they do not always live up to this loaded promise.

After Hurricane Florence swept through the North Carolina processing plant, the open lagoons of waste flowed with the water brought on by the hurricane.

Large pools of blood, fecal matter, and bacteria, along with all the corpses of pigs who had drowned, flowed throughout the state causing widespread environmental and public health concerns.

This incident made surrounding waterways toxic. Smithfield Foods promised to cover the lagoons once the water cleared, but this “solution” does not get to the root of the problem: the excess amounts of pig waste in the first place.

Even without a devastating hurricane, industrialized farming is responsible for heavy resource depletion (water, food, energy), carbon dioxide emissions, loss of biodiversity, and extreme pollution.

In an “isolated incident” that occurred in 2018, a disgruntled employee was found urinating on over 50,000 pounds of pork at Smithfield Foods.

A previous livestock worker at the Tar Heels plant, Keith Ludlum, described the hazardous working conditions; “[management] simply tells you to keep running the hogs. They want to keep their production up. There are tripping hazards and things that they could correct. They choose not to because they’d have to spend money, and it would also slow down their production.”

A Human Rights Watch report details just how poorly employees are treated inside Smithfield operations.

Pork is considered one of the world’s favorite meat sources, and high demand has resulted in the creation of large factory farms that raise, slaughter, and process millions of pigs each year.

Smithfield Foods is America’s largest pig producer, owning the largest pig production plant in the world. The company’s new owner, the WH Group, is now the largest pork processor on the planet.

Smithfield proudly proclaims, “Our business depends on the humane treatment of animals, stewardship of the environment, producing safe and high-quality food, the vitality of local communities, and creating a fair, ethical, and rewarding work environment for our people.”

Undercover footage, natural disasters, and disgruntled employees have proved that all of these claims are false.

Smithfield, and the rest of the animal processing plants like it, has a long way to go in regard to environmental responsibility, employee and consumer safety, and animal welfare.

Correction: A previous version of this explainer incorrectly identified the city of Tar Heel as located in South Carolina. Tar Heel is in North Carolina.