Explainer

How Livestock Farming Affects Climate Change, Explained

Climate•7 min read

Reported

A surprisingly large percentage of greenhouse gas emissions comes from the food we feed farmed animals. But it doesn't have to be that way.

Words by Leah Garden

Global meat production has increased exponentially in the past 30 years. The efficiency of industrial agricultural technology and the science accelerating the production of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and slaughtering mechanisms has streamlined the system, ensuring constant access to burgers, sausage, and wings. But what enables this massive output?

To answer this question, we must look to the sustainer of all life: food. Like you and me, animals destined for our dinner plates are dependent upon caloric intake, living meal-to-meal before they eventually reach a desirable “mass-to-body” index, and are euthanized for human consumption. The industrial agricultural system primarily utilizes feed, or food grown or developed specifically for livestock and poultry.

According to the USDA, more than 90 million acres of land in the United States are dedicated to the production of corn, and the majority of that crop will end up in livestock feed.

A massive amount of land is also required to support the livestock industry. As of January 2021, the U.S. cattle-herd size came in at 93.6 million cows, and the cattle production industry earned a total of $391 billion, accounting for the largest share of total cash receipts for agricultural commodities. These numbers directly reflect the demand for beef in the U.S. As long as demand remains high, the beef industry will continue down this profitable path.

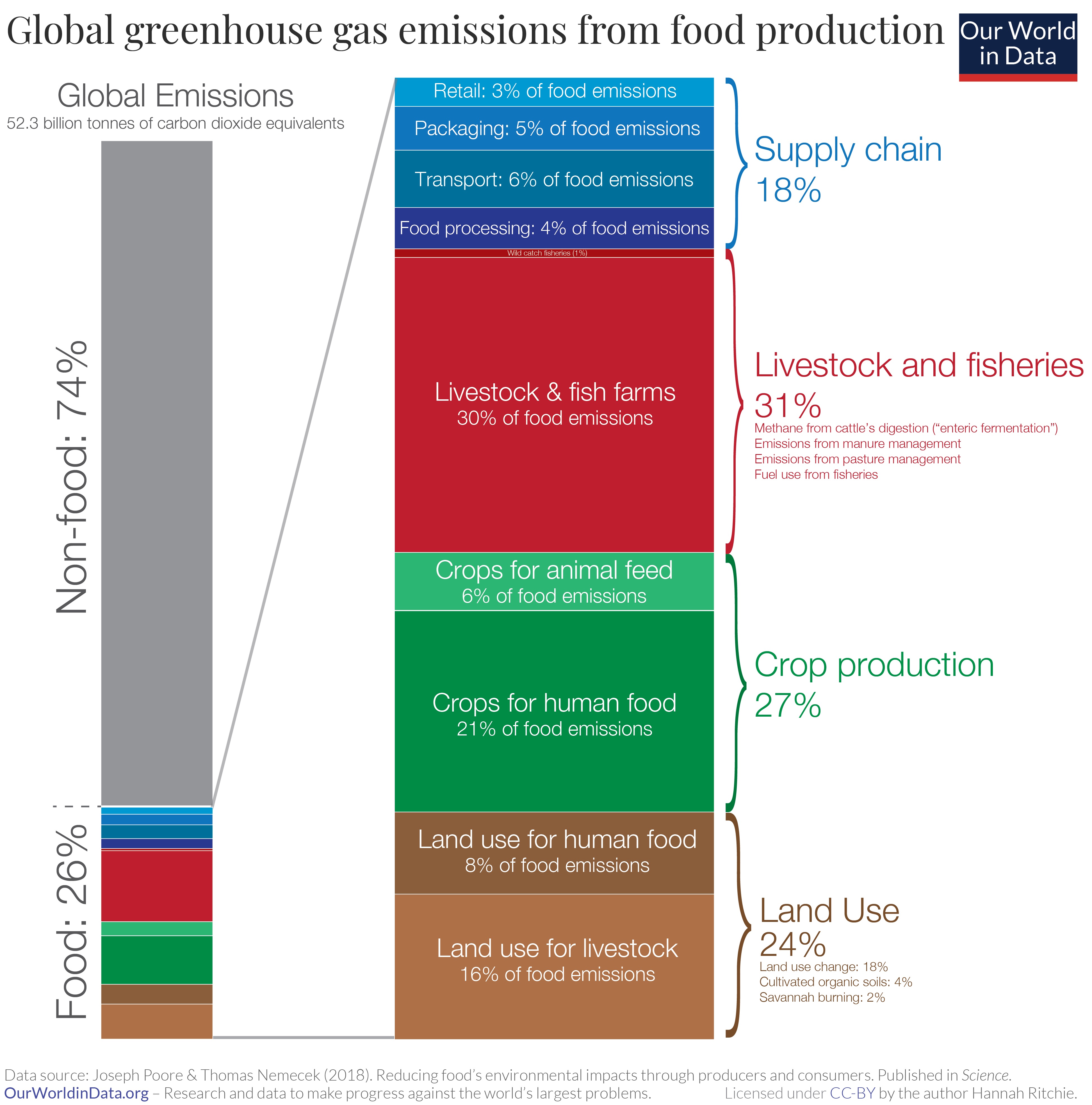

Global food production overall, encompassing meat, fisheries, crop production for both human and animal consumption, and land use-related emissions comprise 26 percent of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, although this estimate is often disputed. Within that number, 6 percent of emissions come from crops for animal feed and 16 percent derive from land use for livestock. In the beef sector alone, feed production contributes 55 percent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; in the dairy sector, 36 percent.

The use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides becomes dangerous for clean water and downstream ecosystems. Nitrogen and phosphorous, two common chemicals affiliated with agricultural production, run off of fields and contaminate other systems, poisoning once healthy water and turning productive waterways into dead zones.

These synthetic fertilizers are utilized to compensate for less productive soil. Healthy soil is comprised of a combination of minerals, water, air, and organic material. When farmers work with the land, the composition of the soil can make or break a crop’s output. As unsustainable practices are used to promote output efficiency, the minerals and organic materials in the soil deplete, rendering the soil ‘dead’ in colloquial terms. Soil health is naturally reoccurring, meaning natural processes will one day revitalize the missing minerals and nutrients, but data shows that the process can take anywhere from 100-1,000 years. No one is willing to wait that long for a cheeseburger.

While grass-fed beef often comes to mind as a sustainable solution to animal feed, past studies show higher GHG emissions and the requirement of grazing land that won’t exist without the destruction of ecosystems in land use conversions. Alternatively, animal feed can go through reform, integrating grains and crops into the main mix of corn and soybeans. But how will planting more crops for animal feed fix any of the existing issues?

Corn and soybeans, the main two contributors to animal feed, grow in the summer months. This means the soil supporting these crops is left exposed and vulnerable to natural weather conditions for the majority of the year. Without roots of vegetables to hold soil in place, the risk of erosion and runoff exponentially increase, negatively impacting the health of the soil as well as downstream ecosystems.

Sustainable Food Lab recently partnered with Practical Farmers of Iowa to investigate the environmental benefits of incorporating cool-season crops into the crop rotation system of the Corn Belt. Investing in the growth of crops such as oats, wheat, and rye during the off-season of corn and soy protects the exposed soil, introducing different and diverse nutrients and adding a new stream of revenue for the farmers.

Local food and beverage companies, such as Oatly, Seven Sundays, and Grain Millers, also partnered in this study to create markets for these new small grains, ensuring financial stability for the farmers adding expenses and new crop rotation techniques to their businesses.

This case study is still in motion, actively testing and recording results to improve financial and environmental output for the future. Utilizing small grain livestock feeding trials, research support, and tools to scale these trials to national markets, this partnership between farmers, NGOs, and corporate entities are paving a sustainable path forward for the feed industry. Data is already showing that “a 10-15% shift from corn to oats in hog and beef rations in the US Midwest can result in a 40-70% GHG savings of the feed footprint.”

An immediate overhaul of the current feed production system may be too financially risky for anyone with a stake in the industry. Incremental change, while frustrating, is the safest path forward, protecting the environment and the farmers who depend upon the earth for survival. This study provides a blueprint for the future of sustainable animal feed production, paving the path for largescale manufactures to locally shift towards a better system.

Animal feed is just one part of the agricultural supply chain. Reforming each aspect (feed, land use, soil viability, animal treatment, and distribution) as one integrated system is the only way to understand how each moving part impacts the other. Only by working together can each branch of our food system form one tree of life, sustaining a healthy environment and the human race.