Explainer

The Deep History of Racism and Speciesism Behind ‘They’re Eating the Dogs’

Election 2024•7 min read

Explainer

Farm subsidies make meat and dairy much cheaper – but fruits and vegetables? Not so much. Here’s why.

Words by Björn Ólafsson

Farm subsidies often get cited as a reason for the problems in our food system. But what exactly are farm subsidies? A subsidy is money from the government that is intended to keep the price of a commodity low. In the agriculture industry, there exist a whole slew of farming subsidies designed to help out farms and keep prices low, including direct payments, commodity purchases and disaster payments. Unfortunately, many subsidies said to be paid to struggling family farmers are actually a way to subsidize the largest farm operations and businesses in the world — especially boosting the meat industry, rather than the production of fruits and vegetables.

The majority of farm subsidies go toward producing feed for animal agriculture. David Simon writes in his book “Meatonomics” that these subsidies are largely for the production of meat: “nearly two-thirds of government farming support goes to the animal foods that the government suggests we limit, while less than two percent goes to the fruits and vegetables it recommends we eat.”

When Did Farm Subsidies Start?

Modern farm subsidies originated in the Great Depression, as the U.S. Government tried to protect the American people through social spending like the New Deal. This included the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which, in part, paid farmers to destroy any surpluses. The idea of subsiding farmers’ output stuck, and many such laws were subsequently passed in the 20th century and beyond.

How Much Money Is Spent Annually on Farm Subsidies?

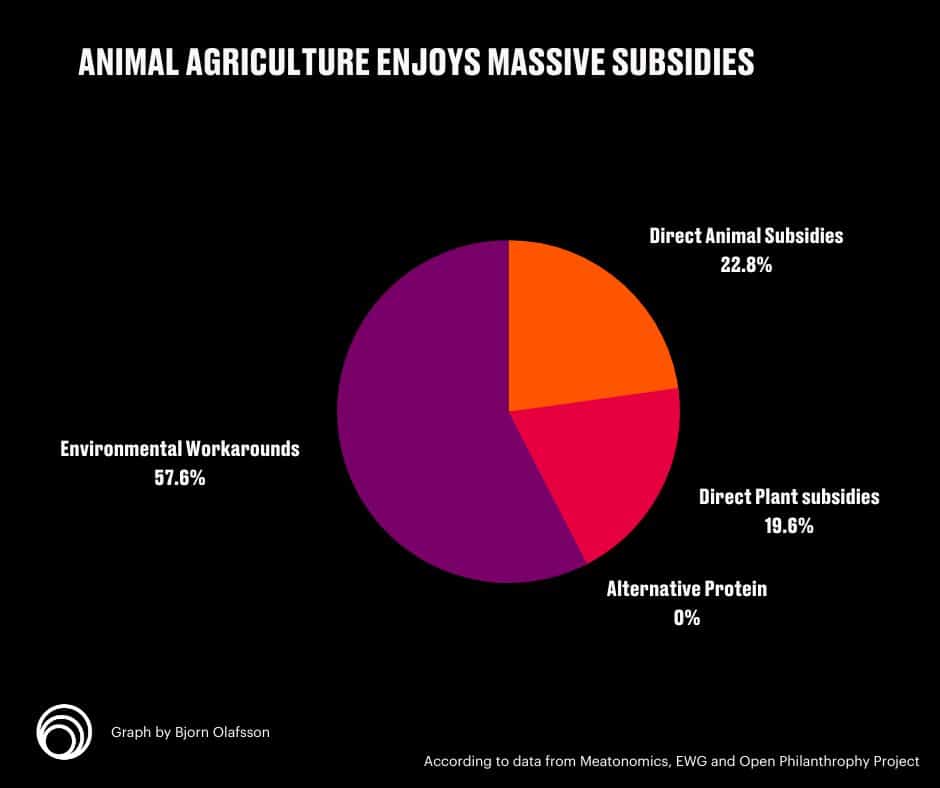

Looking at data from the Environmental Working Group (EWG), “Meatonomics” and Open Philanthropy Project, we can estimate the breakdowns of U.S. agricultural subsidies, both local and federal, all adjusted for inflation.

According to data from “Meatonomics”, the U.S. spends $50.17 billion on animal agriculture every year (including state, local, and federal subsidies) while plants for human consumption receive about $24.69 billion. The meat industry dodges between $80 and $200 billion in environmental costs (the conservative estimate is included in the graph above). According to EWG, alternative proteins net around $30 million (too small to be seen on the chart).

That means the U.S. spends an estimated $75 billion per year, from all levels of government, on direct agricultural subsidies.

Keep in mind that exact numbers are hard to pin down, by design. Not only is the meat industry highly unregulated, but transparency is getting worse. Under the Trump administration, the USDA stopped publishing the names of farm subsidy recipients and has not responded to environmental groups’ requests for clarity. As a result, billions of dollars are publicly unaccounted for.

Ultimately, if you pay taxes in the United States, you’re funding animal agriculture. In 2019, the federal government received $3.46 trillion from taxpayers and spent about $17 billion in commodity purchases. That means for every $100 Americans paid in taxes, about 50 cents directly funds factory farming.

Globally, the situation is similar. According to a 2021 UN report, the agriculture industry is given about $540 billion dollars every year.

How Are Farmers Subsidized?

Farmers are subsidized in many different ways, including by local, state and federal governments. Here is a breakdown of the main categories.

Direct Payments

The federal government gave direct payments to farmers from 1996 to 2014 of about $5 billion per year. Payments were given regardless of what farmers grew, and were based on historical production data from 1986. The direct payment program in the 1996 Farm Bill that set up these subsidies was created to help move farmers from subsidized farming to a free-market model. The 2014 Farm Bill ended direct payments.

Counter-cyclical Payments

The Counter-Cyclical Payments (CCPs) program was a government payment based on the prices for specific crops. Like the direct payment system, CCPs formulas were based on historical data and not current production data. So, “if a farmer’s land was producing cotton at the time when the base acreage was calculated, the current owner will get a cotton CCP regardless of what he is or is not growing currently.”

The 18 crops for which direct and counter-cyclical payments were made were: barley, corn, grain sorghum, oats, canola, crambe, flax, mustard, rapeseed, safflower, sesame, sunflower, peanuts, rice (not wild rice), soybeans, cotton and wheat. These crops are known as commodity crops, and the five largest crops — corn, soy, wheat, cotton, and rice — are known as the Big Five. These commodity crops receive disproportionate subsidies as a result of federal lobbying during the passing of the 1990 Farm Bill.

Both direct and counter-cyclical payments were established in the 2002 Farm Bill and administered by the USDA’s Farm Service Agency. CCPs were replaced with a new system of counter-cyclical payment for farmers when crop prices fall below certain levels, made up of Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) payments, in the 2014 Farm Bill.

Marketing Loans, Ldps And Certificates

The logic behind the government marketing loans to farmers is to prevent them from dumping their corn on a glutted market at harvest time. The farmers can keep their crops in reserve and sell them when they are needed and will fetch a higher price. In this program, farmers use their crops as collateral. They can sell their crop at any time. If they sell when the price of their crop is high, they can repay the loan with cash. When prices are below the target price set by the program, the farmer can repay the loan at a lower rate, keep the difference between that and the full loan, and retain the crop to sell at a higher price.

Instead of taking on a marketing loan, farmers can also opt for a loan deficiency payment (LDP). This is a direct payment of the amount the farmer would have received if they had taken a loan on the crop and repaid at the lower repayment rate when prices were down.

Commodity certificates are another option for farmers who do take loans. They can purchase these generic commodity certificates and use them to repay their loans.

Average Crop Revenue Election Program (ACRE)

Federal lawmakers created the ACRE program as part of the 2008 Farm Bill. It paid farmers a minimum revenue, whether losses were due to low prices, poor weather or other circumstances, and limited these farmers’ access to other subsidies.

U.S. legislators ended this limited program with the 2014 Farm Bill and replaced it with the Agriculture Risk Coverage program, which pays farmers “when actual crop revenue declines below a specified guaranteed level.” The ARC and PLC programs are eligible to producers of 22 crops, including dry peas, lentils, chickpeas and temperate japonica rice.

Disaster Payments

Almost every year, Congress appropriates large sums of money to pay farmers who have experienced losses due to natural disasters. The payments averaged more than $1 billion per year from 1996 to 2010. Multiple disaster payment programs have been created for sectors of the farm industry, especially for livestock producers.

Crop Insurance

Most farmers make more money from crop insurance than they pay into it. The Federal Crop Insurance Program was created in 1938, but it was greatly expanded in 1980 and has since become a major source of cash for farmers. For the most part, crop insurance policies pay farmers “if they experience a decline in revenue or a loss in crop yields.” From 1995 to 2020, about 76 percent of crop insurance payments went to producers of just four crops: corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton — most of which ended up as animal feed.

What Percentage Of U.S. Farms Are Subsidized?

Over 600,000 U.S. farms are receiving federal subsidies, which is about 31.5 percent of all U.S. farms. These farms tend to be larger factory farms, not small family farms.

How Many Subsidies Do Farmers Get?

Each farmer can only receive up to $125,000 in subsidies — however, many large farms are able to jump through loopholes and receive far more. Sometimes family members of farmers can file separately, or landowners and land renters can file for subsidy money in parallel.

Are Farm Subsidies Necessary?

Farmers’ lobbies often argue that subsidies are critical to keeping Americans well fed. After all, farming is essential for our lives, and the government should protect the industry.

However, these arguments fail to account for many factors. First, it’s important to consider that the majority of these subsidies go towards big businesses, not struggling family farms. The majority of this money goes to business executives and investor profits, not to on-the-ground costs.

Who Benefits Most From Farm Subsidies?

Big Farm Corporations

Factory farm owners benefit the most from farm subsidies. By one estimate, two-thirds of farm subsidies went not to mom-and-pop farms, but to the top 10 percent mega-farming corporations. For example, Tyson has received at least a quarter billion in direct subsidies (that we know of) and more than three billion in supply-chain subsidies. These subsidies don’t reflect the reality of the U.S. farming landscape — according to USDA data, over 80 percent of farms are worth less than $100,000 total.

Meat-eaters

In some ways, the average meat consumer benefits from lower meat prices, but it’s important to remember the meat industry’s methods are also diving a whole slew of external costs: everything from extra illness caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria bred on chicken farms, to elevated risk of heart disease and cancer from red meat, to money needed to clean up river contamination at the hands of pig farms.

Totaling up these external costs lurking in the background, and the true, unsubsidized cost could be about $1.70 for every dollar we shell out for an animal product, according to the estimate in “Meatonomics.” A $2.70 Mcdonald’s cheeseburger should actually cost $4.60. That $3 gallon of milk? Over $5 in actual costs. That $4.99 Costco rotisserie chicken? Nearly $8.50.

Subsidies to harmful industries like animal agriculture result in low prices in the short term, but larger costs in the long run.

Criticisms of Farm Subsidies

Most critics of farm subsidies point out that the money harms more people than it helps, especially the environment and public health. Let’s dive into the many disadvantages of the programs.

Subsidies Redistribute Wealth Upward

Small farmers, especially family farms, struggle to keep up with the big guys. U.S. agriculture has been consolidated to the extreme over the decades — up to 85 percent of the meat market has been cornered by just four companies. Unless you are courting farmer’s markets or mom-and-pop groceries, your deli meat selection is likely directly supporting big business.

Subsidies Harm Public Health

The USDA recommends that half of your dietary intake should be fruits and vegetables, yet, due to lobbying efforts, only a fraction of a percent of subsidies go towards these nutrient-rich foods (some of which, admittedly, are much more expensive to produce). The vast majority goes towards meat and dairy products, whose overconsumption, among other factors, is linked to worsened public health outcomes.

Subsidies Harm The Environment

The global meat industry emits between 15 and 20 percent of global emissions and takes up 35 percent of habitable land on Earth, yet it is heavily subsidized. If meat consumption in wealthy nations was reduced, and we rewilded this agricultural land, we could sequester a further 100 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, according to a 2022 climate change report.

As climate analyst Christina Sewell writes, “We can remove taxpayer dollars from animal agriculture, allowing the price of meat to rise to a level representative of the actual cost of its inputs and its wide-ranging externalities. Such a policy would allow freedom in both production and consumption, while organically driving demand for healthier and sustainable fruits, vegetables, and other plant based foods.”

Subsidies Harm Other Countries

As with everything else in agricultural economics, the real effects reverberate across borders. The heavily subsidized U.S. economy harms neighboring countries, especially Mexico and Latin America. As David Robinson Simon writes in “Meatonomics,” “In virtually every developing country where local farmers eke out a living growing commodities that are subsidized in the United States, our policy contributes to reduced incomes, increased unemployment, loss of land, and a decline in quality of life.”

Why Is The Government Paying Farmers Not To Farm?

In 1985, President Ronald Reagan signed the Conservation Reserve Program into law. This initiative was designed to pay farmers to stop using environmentally sensitive land as a way to stop soil degradation — essentially paying farmers not to farm. The program is different from other subsidies, as it’s not related to keeping prices low but to protecting the environment. In 2023, the program comprised about five million new acres of land.

While the program is well-intended, it only protects land for about a decade, so any carbon gains are short-lived. The program also doesn’t have substantial benchmarks for success, leaving doubt as to how much soil is protected and how much carbon is captured. Ultimately, it is a great idea that doesn’t go far enough in helping both farmers and the environment.

The Bottom Line

Regardless of your dietary habits, it is easy to see how the disproportionate amount of farming subsidies that benefit the animal agriculture industry is harmful for public health, the environment and small family farms.

If you support a reduction or elimination of these subsidies, you can voice your concerns to your elected officials. Many of these subsidies take place at the local level, not just federal, so talking to city or state officials can go a long way.

A previous version of this story was written by Hemi Kim.