Investigation

Industry Groups Worked to Expand Wisconsin Bill Meant for Small Dairies

Factory Farms•7 min read

Perspective

Reflecting upon my history in animal advocacy, I realize that I have undervalued my family’s roots as a key factor in why and how I want to help animals to live a life free from suffering. I’m ready to change the narrative.

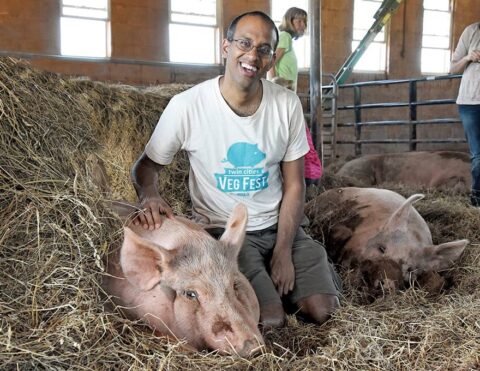

Words by Unny Nambudiripad

When I was ten years old, I was visiting family in India and met a kitten named Bobby who would change my life forever. I didn’t know it at the time, but later—after much soul-searching and a deep-dive into a social justice movement dominated by white people—did I realize that it was meeting that sweet little kitten that sent me on my journey of both animal advocacy, and eventually, to recognizing how my Indian heritage was its driving force.

My parents were born and raised in India, and I have visited family and traveled there every few years from my home in Minnesota. When we’d visit, my cousin Narayanan would watch over my brother Krishnan and I. He would show us many aspects of living a full life, such as having us taste the leaves of the nearby allspice tree which had not yet provided seeds (the leaves taste like the spice!). Even now, I smile when I think of how nonplussed Narayanan appeared, bringing to his communication a gentleness that, years later, I still value.

Narayanan befriended a semi-feral kitten whom he named Bobby (after one of his favorite chess players). Bobby was a sweet and friendly kitten, and Krishnan and I were totally smitten. Thinking we were just playing, we threw this little kitty higher and higher in the air, until Narayanan said to us, “If you keep doing that, Bobby will die.” My brother and I were gobsmacked; we thought we were just having fun. We were mortified.

Krishnan and I didn’t realize it, but we were being cruel to this precious individual, this darling cat. As soon as I connected the dots—that this gentle soul was as sentient as me and my human friends—I felt ashamed (despite Narayanan’s non-judgmental tone—which later became a touchstone for my own activism). Until that moment when I was confronted with my own unintentionally cruel behavior, I hadn’t thought of myself as somebody who would be cruel to any animals.

A decade later, as an adult, I happened across Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation—a game-changing book that helped launch the modern animal protection movement in the West—and immediately got involved in advocating for animals. I appreciated the clear logic and methodical thinking, and I felt new horizons of understanding the world and my place in it. I didn’t ponder my own story or think about Bobby.

It wasn’t until several years later when I was reflecting on that particular visit to India and latching onto that experience with Bobby that I realized it was, in fact, that cat—as well as my cultural heritage—that were the driving forces behind my animal advocacy, even more so than the philosophy presented in Animal Liberation. I suddenly saw everything differently. For the first time in my advocacy, I recognized without a doubt that the main protagonist in my story was me.

When I learned the truths about what happens to animals behind closed doors, it was as powerful as when I learned that Bobby was sentient, and that it was my job to protect him. And so I found myself getting involved in animal advocacy, which, as it turned out, is a predominantly white movement.

The animal advocacy campaigns that I participated in framed our work as rational. The goal was simple: to carefully determine the best ways to reduce suffering in the world. That logic called to me and I wanted to do my part, so I showed up—to protests, to grassroots events, to vigils.

I actively participated in the storyline that my fellow animal advocates deduced were the best ways to reduce suffering in the world. And while that is a worthwhile goal, what I didn’t see was that the values and reasoning we animal advocates used were centered on the beliefs and experiences of mostly white people, and were flawed by their very nature.

By taking part in campaigns that were organized by white people, based on research that was found by white people, and influenced by books that were written by white people, I helped perpetuate the myth that the way to help animals was by doing things the prescribed way, the white way. This was further underlined by my emphasizing the philosophies, experiences, and stories of white people who were often in leadership positions in the animal protection movement as I knew it.

Where did my brown skin and my very own perspective enter the story? In fact, was it ever sought out?

Parallel to my animal advocacy, I became involved in other equally important causes: promoting clean energy, challenging sexual violence, and advocating for workers’ rights. Through these activism channels, I was able to attend several anti-racism workshops and work alongside a diverse group of people. These eye-opening experiences introduced me to new ways of thinking and living. At workshops and conventions, participants would often ponder questions such as: What’s our story? How did we get here? Where do we go from here?

As it turns out, the stories that make us unique are the same ones that make us activists. I had never considered that before. Only then did I recognize that my experience with Bobby the cat—recognizing his sentience, understanding my power to help or hurt—was my first concrete belief in the sanctity of all living beings.

My journey into these adjacent social justice realms was indeed changing me, causing me to reflect on my animal advocacy—amongst other things. As I began to self-analyze my role in this movement to help non-human animals, I started to recognize that my own path to animal advocacy was, in fact, not led by white folks or folks from the West. Finally, I was seeing things clearly; it was my heritage that got me here.

My Indian heritage has a long history of treating certain animals with compassion and respect. As one example, vegetarianism has been in my family for countless generations. When my parents came to North America, their traditional religious and cultural practices were fading—becoming white-washed, much like my own view of animal advocacy later would. My mother continued to be a vegetarian, and all of us ate vegetarian food at home, but nothing drove the rest of us to abstain from meat outside of the house; like so many others, in this way we were sleeping. We were letting the culture of the West influence how we behaved, how we showed up in the world, and the ways we rationalized our behavior (of course, vegetarianism and then veganism restarted for me as an adult).

It turns out that my lineage had played a greater role in my commitment to ending animal suffering than I initially understood. I just needed to reconnect with my roots in order to reconnect with my advocacy—but this time, it was my own experiences (not the ones written about by a white man) that informed my activist beliefs and tactics.

People of the global majority (those who identify as Black, Brown, Indigenous, Asian, and Pacific Islander folks, and those who are mixed) have always been involved in animal advocacy, both in the United States and around the world. However, most of the attention from the media and even within the movement focuses on the work led by white people. Even I let that societal norm be my guiding light … until it wasn’t.

This reliance on the white experience has limited the power of the animal advocacy movement and kept us from considering the myriad approaches and beliefs regarding animal advocacy. We have inadvertently placed the white worldview on top—which is exactly what happens in our society when there’s not a conscious effort to look at things another way.

The white-led animal protection movement has also avoided facing the suffering and oppression that people of the global majority experience, which ultimately has been holding us back from creating a more just and fair way forward. This has significantly limited our collective power to create systemic change for animals, and it’s time for me to get involved in a different way.

I am genuinely grateful for anybody who is advocating for animals—many of them are my role models—but I also see more powerful opportunities for creating lasting change. Prioritizing equity and turning the table on white-led constructs will lead to a more effective movement—one that can have an even greater ability to help animals.

The way out of the limitations we have built is surprisingly simple: look to people of the global majority who are already doing work for the animals and support them, fund them, and get behind them.

Specifically, individuals and organizations in the animal protection movement can seek out opportunities to provide funding for groups led by people of the global majority. Our movement can prioritize the goals, aspirations, and values of communities of color who are working to end animal suffering. We can focus on providing leadership opportunities, jobs, and board seats to people of color.

Supporting people of the global majority—amplifying these voices—is a path to helping more animals, and to creating a more equitable and powerful movement.

It took decades for me to recognize Bobby’s influence on my life, and help me see animal advocacy and my own life story in a different light.