News

RFK Jr.’s New Dietary Guidelines Tout Meat, but They Could Actually Open the Door for More Plants in School Lunches

Diet•8 min read

Perspective

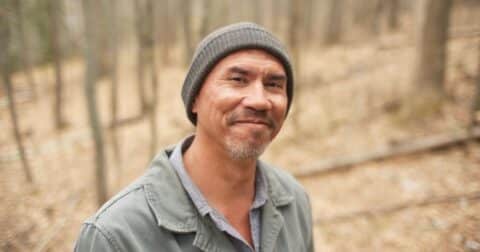

Sentient’s Ana Bradley and Jenny Splitter speak with journalist and author Brandon Keim.

Words by Ana Bradley

Our understanding of how animals see the world is changing, almost on a daily basis, as more and more scientific studies reveal their inner lives. In this new episode of Sentient: The Podcast, Sentient’s Executive Director, Ana Bradley, and Editor-in-Chief, Jenny Splitter, sit down with journalist and author Brandon Keim to discuss his new book ”Meet the Neighbors” and get to grips with the latest science around animal sentience.

Related Links:

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-25935-010 Hobaiter, Catherine

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2024/06/new-anthropomorphism/678611

Transcript

Ana Bradley

Welcome to the Sentient Podcast. My name is Ana Bradley. I am the executive director at Sentient. And this is our first interview since our rebrand earlier this year and our first conversation, where we have our Editor-in-Chief Jenny Splitter, who’s going to co-host with me today. And I am deeply excited about this conversation. Because as those of you who have listened to this podcast before, the reason I set this up was to talk to people who are really changing the way that we think about and interact with the world around us and the inhabitants that we share the planet with. So like who better to speak to than Brandon Keim. Brandon is an independent journalist who specializes in science, nature and animals. And we’re here to talk about his book, his latest book, Meet The Neighbors, which follows on from his first book that I have the Sandpiper, which I also absolutely adored. And Brandon’s work, aside from these books, has appeared in The New York Times in the Atlantic in Wired Nautilus. And yeah, when I get started with you, Brandon, thank you so much for taking the time out to speak to us today. We really appreciate it.

Brandon Keim

Oh, thank you. Thank you, I’m, I’m honored both of you.

Ana Bradley

Okay, so I just want to kick things off by addressing the title of this new book. I find it, like, so clever, and also confronting in a way, like, we at Sentient think a lot about the language that people use to describe animals. And you talk in your book about these animals that many people would consider pests like rats, and even coyotes. And you’re like, you’re taking that language of like pests and stuff, and turning it into this idea of actually, these are our neighbors, and you go on this really, like tangible journey, that you can just feel like you’re walking there with you through your neighborhood, telling the stories, you know, of each of these animals in a way that like, is framed in science, but also, like, kind of personhood of these animals. Like, I’m just so curious, like, what motivated you to create that kind of framing and tell the story in this way?

Brandon Keim

Yeah. Well, I’m really glad that resonated with you because that, that, that section, so that’s sort of the first section of the book, because that, you know, walk through an everyday Eastern American suburban neighborhood. And, you know, and looking at the non-human, the non-human residents of that neighborhood and kind of mapping the science of animal intelligence onto them. Until like, back when, when I first thought that I might write a book and meet the neighbors will still a glimmer in my eye, it was really going to be much more of a straightforward science with the animal intelligence, but because that’s, that’s where I was coming to the subject material from was as a daily science journalist. And, you know, so over over time, it became much more of a, you know, so here’s the science. And so what are we going to do with this book, but still, that first section is kind of, you know, a distillation of the book that I would have written. And, you know, what I was really trying to get out there. There’s sort of two, two things. So one of them is that, you know, like, we live, like, we live at this amazing moment for the scientific study of animal intelligence, right? It’s like, every day, there is some interesting new finding, you know, and it’s kind of really gone from, you know, even just a few years ago, there was a sense that like, oh, okay, well, you know, chimpanzees and whales and elephants and like, and crows and ravens, of course, you know, there’s this sort of handful of extra Smart species, you know, but that’s kind of where the animal intelligence discourse was. And now it’s just like, No, right? Like, there’s these, it’s forms of intelligence all over the place, I mean, in you know, in, in a great many species, and so, so I wanted to really capture that and also capture, you know, make, make those insights feel more approachable and organic. And, you know, I think sometimes I find with myself, you know, like, I’ll read, I’ll read a new story about a find an animal intelligence finding, you know, in it can still be very abstracted, right? Like, so much of it is about, like the methodology of the study. And this is taking place in an experiment, and they’re still kind of that, you know, veil between you and the animals. It’s almost like the story is about the animals and yet, in a weird way, the animals themselves aren’t fully present. So I wanted, so I just wanted to make you know, those findings and that appreciation of the minds of other animals really come more alive than it does and kind of unusual, you know, and this study says, And this study says so on. And then there’s also just a sensibility, which is really something that you know, that grew for me when I was living in the suburban yesterday. Good, where that first section takes place where, you know, and I talked about this earlier in the book where there’s that there is this little, there’s this little stream that I used to like to go and sit beside every morning, you know, it was like a storm water. It was a stormwater drainage stream that went into a big storm water retention pond, but it was still a very natural and lightful place. And so I used to love, just, you know, every really, at the beginning of every day, at the end of every day, I would just go and sit by the stream and gather my thoughts, and maybe I would do work and whatever. You know, in the same place, every day, I was seeing the same animals that you know, in, especially birds, there are a great many birds who came and, and would bathe in the street, you know, cat birds and mockingbirds, and sparrows, and starlings and you know, the whole community. And it was really with them, that it sunk in for them, that is sunk in with me, you know, that like, like, these creatures, like, this is just where they lived, right? This is their morning routine, you know, it was just like seeing somebody at the coffee shop, or the gym, you know, and then like, it really made me appreciate that I was living in a community, this, you know, of, that was full of both people and animals, you know, and then later on it, I do try to take that sensibility really out into the world. So it’s not just about the animals who live around us, although I think they’re, they’re enormously important. You know, but really, that, that attitude is something that can encompass all animals. And I should say, also, not just wild animals, and maybe this is something we can get into later in the conversation and kind of how to, you know, where, where one draws the line, as an author in, you know, in sort of, who I’m writing about, and trying to write about the animals in a very, you know, in a very animal forward way, that walks the line between not saying to people, Well, you better be vegan, if you’re thinking this way, because if not, you know, but at the same time, also not sort of re inscribing, the lines that we do draw between the animals, all of whom should be thought of as fellow persons. I don’t know if that last bit made any sense. But hopefully, so.

Jenny Splitter

That’s like everything we wanted to ask you about. Very nicely, because this was mentioning when Ana and I were prepping. I think I also messaged you, you know, along those same lines, like I think that was highly effective at making the whole topic feel very accessible, because I feel like I’m not someone who, you know, there’s people who just like, read and devour every book about wildlife. And I’m not really one of those people. And so I felt very much like, oh, but also wildlife, you know, happening all around me. Like, I felt like I was immediately kind of drawn it, which was really great. And so I love that you mentioned this kind of like moment of the science of animal sentience, because that’s also what I wanted to ask you about. Because I, when I joined Sentient, I, you know, I hadn’t really covered any of that, that sort of area as a freelancer, as a science journalist, myself. And so I felt like, gosh, there’s like a million things going on all the time in this field. And I guess what I wanted to ask you is like, did, was there some inflection point recently, you felt like were all of a sudden everything sort of unlocked? Or was it because you do kind of start with sort of you bring us back to Darwin and kind of start about some talk about some of the origins. But yeah, I guess just having not really, you know, covered the field myself. Is it sort of like, you know, things are going along, kind of at this pace? And then all of a sudden, something kind of blows everything away? I don’t know. Or was it my imagination that everything you know, was exploding recently? Sounds like No, also, there’s a lot going on right now. But yeah, I just wondering as someone who like, covers this more closely, how you look at like, the field and inflection points, I guess.

Brandon Keim

You know, there’s probably, there’s some probably some enterprising postdoc out there who’s like, done the literature search and has the graph that they could show us but like, I definitely feel like we’ve hit some sort of inflection point. I’m going to say maybe, you’ve seen maybe like, the last five years or so. I’ve really felt like this for me, like, I think like the, you know, like the mid to late 2000s are, for me, at least when things you know, the pot really started boiling, or at least bubbling. And then, you know, it just kept on getting you know, there was just more and more activity throughout the 2010s. And sort of, you know, finally getting to the point where, where we are now and you know this others. Actually maybe a couple of good signposts for thinking about this. So I think it was back in 2012, there was the Cambridge declaration of consciousness where a group of scientists said that, if I remember correctly, that there was ample evidence to say that mammals and I think it was mammals and birds, or at least like mammals, and maybe many birds or mammals, and probably birds, could could be considered conscious, and that this should be an uncontroversial statement. And then very recently, there was sort of an update to that, you know, where it was an official statement from an even larger group of scientists saying that sufficient evidence existed to consider pretty much all vertebrates and integrate many invertebrates. I’m conscious as well. And I think, you know, and so like, like, their announcement wasn’t just like, some new study was done yesterday, that shows that all the animals are conscious, it was, you know, the combination of findings that had been accumulating across this time. So I think, you know, we really have had this tremendous efflorescence of these insights. In the last, you know, five years or so. And it’s also I think, really bubbled out much more in popular culture, and, you know, one one here so much less frequently, these days, you know, the charge that you’re being anthropomorphic, if you, you know, if you see other animals, this thinking, feeling beings, and, you know, there have been enough, I think there have been enough books now about the science of animal intelligence, that these ideas are kind of notice sort of much more, much more ingrained in, in the general consciousness. And I think, where things are getting interesting and sort of where there’s still, you know, where there’s, there’s still a lot of gonna say, uncertainty is the wrong word, but basically, so so we’ve got the science and now now we’re all just trying to figure out all right, like, what, what are the implications of all of these insights for the relationships that we have with the animals, whether it’s the animals who are used in food, or research or companions? You know, we’re wild animals, like in my book.

Ana Bradley

This might be a little bit like, outside of where we’re going. But like, thinking about the science and thinking about how it’s altering how we’re perceiving animals, I feel like there’s this line between like curiosity, like presuming curiosity, or choice of action in animals, and like full disclosure, I spent like a month in Cape Cod earlier this year, and I last night, watch Jaws, because I felt like I have to, like, pay homage to, to my Cape Cod time, I was too scared to go in the water. Watching Jaws last night, I was like, it is so interesting, and how much has changed in our perception of animals? But also how little because, you know, as you know, Brandon, I spoke to you about this briefly last year, as well. But Walker, you know, the alleged Walker attacks that we’re seeing on boats, have, they’ve resurfaced again this year. And people are, there’s more media coverage about this, you know, the Orca conspiracy of, you know, trying to conspire to take down yachts or whatever. And that compared to Jaws with this idea that there’s the shark that exists to just, you know, screw with people. And it, it kind of breaks my mind a little bit, because it’s like, think this thought that these animals are being intentionally cruel. And then we have this science coming out talking about, as you say, more and more talking about sentience, and talking about the way that animals perceive the world? And I don’t know, like, do you feel? How do you kind of think about the, like, the difference between, like, choice and curiosity within animals? And how, like, how should we be thinking about the the behaviors that we’re seeing?

Brandon Keim

Yeah. So you know, that’s, I really, I really liked that, that parallel between where that example of the, of the shark in Jaws, and then the way that we’re perceiving those workers, and I think so that that really also brings in the the social construction of the animals, which is like another whole piece of this right. And that’s something that I think, you know, so for me, as a science journalist, it’s been really, really revelatory to understand that, you know, so much, so much of what we think about animals, you know, really comes out of this interaction between what we actually know about animals and then the social narratives that exist around them. And you know, and it gets real messy real fast, right? And so, you know, and in with the, so of course, Jaws, right, like I don’t, so I’ll confess, I only dimly remember Jaws, and I did not watch the sequels.

Ana Bradley

I watched the sequels, nobody should watch the sequels

Brandon Keim

If I remember correctly in one of the sequels, like, the protagonist of the first movie had moved to Florida or something and like the shark like followed him down there to take vengeance, which is, which is awesome. But like that, that aside, you know, the portrayal of the shark in Jaws, it’s kind of this almost just this, like, killing machine, versus what is a relatively more nuanced understanding of what’s going on with orcas striking. And like the so the worker coverage has been all over the place to right, like there’s the, you know, kind of that initial idea that they were attacking the yachts and I think the science is settled more now on it’s about that, you know it’s a form of play. And but also like the difference between what you will see in you know, like a really scientifically informed story written by somebody who, you know, read it by a reporter who talks to people who study whales is so different than like what you see in like the tabloid, like the tabloid and quick click press, and weird, you know, it’s just so so much sloppier? And, you know, and so I think it was, so I think it was interesting, the way that like, the idea that they were attacking is something that, you know, we just, like, very quickly went to that, and I think, you know, and I think it says something about us that, you know, we perceived what they were doing, in terms of an attack in the first place, you know, no, of course, that was helped by the fact that they’re attacking the boats of rich people, which, you know, is something that, like, 99% of us support wholeheartedly. But, you know, but I’d say there is a, there’s been at least, like, more of a sense that those workers, you know, are not just kind of like, rigidly following some instinctively prescribed path, which is also one of like, violence. You know, there’s, there’s not so much essential sense of that, like, people are more open to the possibility that they might be playing or maybe it’s a maladaptive cultural response where, like, you know, these are just workers who, you know, have not had good role models. I mean, there’s, there’s, there’s more nuances, at least now, nowadays.

Jenny Splitter

Oh, I want to ask about some of these, that your your coverage of sort of the legal status of animals, but before we go into that, actually, stay on this topic of the word I can’t pronounce anthropomorphized.I know, something that always gets, like, stuck, like in between my brain and my mouth when I try to say that word. But anyway, there was an article recently, in the Atlantic, I don’t know if you saw that about how researchers like, think about their own, anthropomorphism of animals, and whether like, I think it was like, you know, this idea of, you know, first there being like, Oh, we don’t want to do this, and then kind of like, well, maybe we just, like embracing it like we do in any way. So let’s do it. And so I guess, you know, that’s another thing that’s kind of like changes, there’s a lot of not a lot, but there’s at least some coverage of of like the field kind of taking stock of itself, which is kind of interesting. And it just, I’m thinking the part of your book, where you talk about kind of like the birds building nests, and people thinking of it, like disparate scientists dismissing it as kind of like, oh, that’s just instinct. And then what is instinct anyway? I just kind of like blew my mind, because I was sort of like, yeah, how do you how can researchers, I don’t even know what question I’m trying to get at is just more like, I’m kind of, like, struck by how difficult I guess it is for for, like, I can’t imagine trying to figure out, you know, what the dividing line is between, like, animals teaching each other and, versus just like something that’s instinct, because it’s not like a simple test, you can just, you know, check. And so I guess I’m wondering if you have just thoughts on that of like, I don’t know, like any researchers that stand out in terms of, you know, kind of like being able to reflect on their own kind of biases, I guess, in a way that’s, that’s kind of good.

Brandon Keim

Yeah. Um, so I think so first of all, I’d like to give a shout out here to to a researcher named Gordon Burkhart. And he’s kind of one of the, like, really one of the pioneers of the study of reptile intelligence. And, you know, he’s, he’s, I think he might actually be a professor emeritus at this point, you know, he was an old school type, you know, who really came up in the scientific environment where anthropomorphism was just, you know, like, it was really, you know, it was an insult that you would hurl at a researcher, not something to think critically about. And so he actually coined the term critical anthropomorphism where he said, No, you know, you know, anthropomorphism, which are any, any of your listeners or viewers who don’t know what the term is, you know, it just means interpreting the behavior of an you know, of another entity, usually another animal, sort of, in, in human terms, in terms of human behavior. And, and it’s generally your historically, it’s had a negative connotation, right? Where the idea is that if you’re doing this, you know, you’re kind of being overly sentimental or not thinking critically about about that comparison. And so Gordon Burkhart, coined the phrase critical anthropomorphism where he said, Okay, you know, anthropomorphism, this isn’t a bad thing, right? Like we, we exist on an evolutionary continuum with other species, not just in the composition of our bodies, but you know, in the, in our mental processes, and to kind of deny that human to deny that, you know, human behaviors could be a lens through which to see animal behaviors was just nonsensical and counterproductive. So that being said, you also need to be very careful about it, and maybe, maybe an easy way of, of illustrating that would be, you know, if you take the average, the average mole who, who doesn’t really make use of their site at all, because they’re subterranean dwellers who rely mostly on smell and touch, so you’re not going to go far in thinking about what a mole experiences, if you’re thinking of them as seeing, I mean, that’s, that’s like a really simplistic example. But that’s kind of, you know, an obvious way in which the the human experience and the mobile experience don’t line up. But so if you, but if you think rigorously about it, then it’s okay to be anthropomorphic. And this is a tool that we can use to help understand and to help study other creatures. And, and I think, really, the, you know, that’s something where, especially with younger scientists coming up these days, anthropomorphism is not a bad word anymore. And people, you know, and researchers really are reflecting upon how best to, you know, use that perspective, you know, how best to harness that perspective, and, and not to be afraid of thinking of, you know, animals doing things in ways that we do, or us doing things in ways that animals do, it’s, it’s easy to kind of make the formulation still all about us. Right, that it goes, it goes in both directions. And then just like the, the research that happens, you know, I I’ve been critical about, you know, the ways in which sciences, you know, kind of had its head in the sand about animal intelligence for much of the last several centuries. But I think sort of one, I’m not gonna call it a silver lining, but a silver ish lining, is that in order, in order to make claims about animal intelligence, researchers have really been forced to come up with very strong evidence. And that means strong experimental designs and strong methodological practices. And some of the ways of studying animal intelligence that they’ve come up with are just so ingenious and clever and like, so the two, like the two studies that jumped to mind when I say that, one is the kind of now now famous work on Bumblebee emotions. And you know, that the, the way that researchers have been able to get at the emotional experiences of bumblebees, is by harnessing something that’s known as cognitive bias test. So this is the cognitive bias basically means like in humans, like, you know, Is the glass half full, or is it half empty, and like, if you’re in a good mood, if you’re happy, that glass is half full, and if you’re a bad mood, you’re unhappy, the glass is half empty. And so then with bumblebees, let’s say you can sort of train them in a setup where if they, if they press a red button, I can’t remember if they’re actually pressing a button, but you know what I mean, if they press the red button, you know, then they get a sweet drink if they press a year, or I’m sorry, if they press like a blue button, they get a sweet drink. And if they press the yellow button, they get a really sour drink or a bitter drink. And then you present them with a color that’s just sort of halfway in between blue and yellow or whatever color it is. And then are they are they going to press that button and take the chance? And if they’re, you know, if you’ve just like shaken up their hive, or I guess bumblebees, don’t live in hives, but if you’ve just you know experienced if you’ve just exposed them to something that is known To be a physical stressor, you know, that you would assume would stress them out, well, then they are going to be more pessimistic, they’re in a bad mood, they’re less likely to, you know, press that indeterminate Lee colored button, then if they’ve, you know, been eating and the temperature is right, you know, and had been in conditions that one would think, would foster positive Bumblebee aspect. And so those bees, you know, they press that button, they’re like, already the world’s good place, you know, I feel good. I’m going to take that chance. And so just that, like, you know, just that study design, it’s kind of so simple, and so brilliant. And then another one other study, I want to mention, even with the question of self awareness is this whole, whole big thing we could talk for, like, the rest of the hour about? That kind of is a quick synopsis of where things are at these days, it’s just that, you know, once upon a time, it was thought that self awareness was something on the human’s head, and then we’re like, Well, maybe it’s, it’s humans, and, you know, chimpanzees and Asian elephants, and maybe manta rays and a few other species. And now there’s much more of a sense that, you know, self awareness is something that exists in a great many forms, it’s just not a human style of self awareness, and nothing else, you know, in that you can have sort of, you know, these extremely complicated forms of self awareness. But then there’s also very simple fundamental soul forms of self awareness. So basically, just knowing that you, were you, you know, that, that the experiences you were having argue that you’re not the same entity as your surroundings, this is sort of what’s called pre reflective self awareness, or a body self awareness. And one way of getting it this was used in this, this study that was done with rats, snakes, so rats, snakes, you know, like the, almost this cartoon image of like, you know, like a rat snake before eating just looks like a snake. And then after a rat snake is even a rat, they’ve got a big, a big rat shaped bulb in their, in their middle. So you present them, you know, they have to go from point A to point B. And in order to get from there, they have to pass through an opening. And so before they’ve eaten, they will go through a small opening, because of course, that’s going to fit their bodies. But after they’ve eaten, and their middle has expanded, then in order to go back in the other direction, in order to get from point A to point B, they’ll go through the correct size hole, they won’t try to cram they’re now swollen bodies through the original small bowl, but use the one that’s the right size. And so that, you know, that is a way of illuminating, you know, that they are aware of their bodies. And that is just like a fundamental part of the self. But so again, just like the most simple way of studying something in yet just brilliantly clever the same time.

Ana Bradley

It’s there, obviously, you covered so much there, Brandon is asked for us to digest like the rat snake. So that like, I feel like I feel like one of my like, the things that I always hate is when we look at these studies, and it’s done from such like a human centric point of view that you feel like you’re just missing everything, like trying to think of these animals as perceiving the world the way that we do. So it’s really super interesting to hear about this new approach where this critical entrepreneur, I can’t say it now, there’s a critical anthropomorphize station, whatever, of these animals and of the workers is going is in place. And I think like, what stands out to me throughout everything that you’re saying there is like, what, if we know all of these things? You know, at Sentient, we do a lot of tracking on trends. So we’re constantly seeing that more and more people. As you say, over the last five years, we’ve tracked this transition to where more and more people are actually Googling and searching for information about animal sentience. Do lobsters feel pain? Like the cows like being milked? You know, like, Do animals are animals sentient? What animals are intelligent, etc, etc. We’re seeing this increase like year on year in terms of what people are looking for. And it kind of makes me feel with this, you know, everything that you’ve just laid out there with this idea that people are thinking more about these topics, and about, you know, pain and sentience and intelligence, and you know, personhood, like, what is our responsibility? Like, how should we act on that? Like, what, what should the takeaway be? And especially when we’re thinking, you know, as you bring out on your book, and as you mentioned at the beginning this, like, we have the wild animal approach, but then, you know, obviously, we know that the vast majority of the animals on this planet are farmed animals. So how do we how do we square that? How do we think about like, what, what is our responsibility, I guess, to the to the wild and the farmed animals as a result of knowing all of this information. I

Brandon Keim

mean, that that is the essential question that comes out of this and I would argue it’s you know, the, the essential question at the heart of the fate of the rest of non human life on Earth, right. And, you know, and so the way that I think about this, let me try to let me try to put a couple threads out there and then see if they can weave them together. So, so one of those threads is that I think, the more the more we understand about the minds of other animals, the more we appreciate how arbitrary the lines that we draw between them. And I mean, not just the scientific lines, but the ethical lines, where, you know, there are some animals who are, were farmed animals. And so for the most part, they’re just invisible to us, and we don’t think about them. And then there’s the animals were used in research, and of course, our command companion animals who are the animals who get to be, you know, full persons, for the most part. And then, and then there’s wild animals who kind of, you know, also occupy what’s almost an in between space where sometimes they’re visible, and sometimes they get to be individuals. And it really depends a lot on on context. And so one of the things that I hope Meet The Neighbors does is, is really provide a framework for understanding kind of how those lines came to be drawn in the first place. And kind of what is this, like intellectual infrastructure, we inherit in how we think about animals. And then I argue that at least, you know, when it comes to animals used for food, and in research and our companions, and what have you, you know, the conversations around them are are happening, right? Like the, the change isn’t happening in the world as quickly as many of us would like to see. But at least this is something that’s on people’s minds, and people are thinking it through. But when it comes to nature, this is really, you know, like an animating principle of Meet The Neighbors. But when it comes to nature, that sense of seeing wild animals, this fellow persons, you know, it’s just really something that has been pushed to the margins of popular culture for more than a century and never, you know, never entirely extinguished, that kind of not considered serious knowledge, and not really incorporated within, you know, the frameworks, or the lenses that usually mediate the way that we see nature and think about wild nature. You know, so whether it’s, you know, conservation biology, or sort of, you know, the idea of nature is beautiful, or ecosystem services or transcendence, or, you know, just sort of all of these lenses that we have, like, you know, you know, animals as fellow thinking, feeling beings with meaningful communities in relation to their own, just kind of really don’t appear, right. Um, and so that’s what I’m trying to get at with, with Meet The Neighbors is the what the wild nature part of that. And then when it comes to, sort of, okay, so what are our ethical duties and our obligations and just, you know, like, the way we should be be leaving with our kin. You know, it’s like, I’m always very happy to talk about where we are my own thinking has taken me and what my own answers are. But I also, you know, I don’t want to, I don’t want to, I think the very first thing we owe other animals is to take them into account this way, and to sort of make this understanding of them as fellow persons part of the equation, part of the moral equation, whatever the moral equation is, for us, wherever we’re, whatever those calculations take you, we should at least be clear, and about who they are. And once that’s taken into account, like I don’t, you know, I don’t want to tell other people where I think they should end up, although I certainly have ideas about where I’ve ended up. But I do want to give people sort of tools for thinking about it, and then tell stories of people who have taken these insights, you know, out onto the landscape and into the world. And, you know, and often that people doing that, you know, just like the rest of us, they might not be fully consistent. Like this isn’t, you know, a book about, you know, nine, nine stories of vegans in nature, but it is, you know, just a book about people who are wrestling with what does it mean to think about other animals as persons and what does it mean to think of them as Kim? And just trying to go forward with that?

Jenny Splitter

Have you I think about this a lot like in, you know, having some of these conversations like what are ways that make it a conversation essentially, about how to look at animals versus just, you know, a monologue or shutting down or what makes what kind of like, makes people resist versus like, what makes them what unlocks curiosity? And I guess Yeah, like, either like in the course of interviewing so many people are just talking people about the book, are there are there sort of, like, kind of bigger, like aspects that are or, or things that seem to do that more successfully? You know, then then other I mean, obviously, we can think of things that are, would not be successful, but like were there things was like, Oh, this was surprising, you know, like, I had a conversation this way. And I thought the person was going to be kind of resistant. And I don’t mean, you know, about like veganism, but just like, just thinking about animals and talking about them, you know, in an engaging kind of way. But I

Brandon Keim

think one, one thing that’s really, I think, really helpful and, and reassuring, is that really like, like, everybody loves animals, right? Like, we like, we’re usually pretty inconsistent about it, but like, it’s some level, everybody connects to animals. And certainly, like when we’re children, like, like, pretty much, almost all children just have that like, instinctive feeling of connection. And it can get overgrown with time. And it’s really hard to keep that alive, but like it’s there. And I think, often, you know, it’s not difficult for it to come to the surface. And, you know, and I think sort of in just engage in on I don’t want to sound trite, but like, engage with what we have in common, right? Like, you know, and don’t answer, there’s sort of the obvious, like, the obvious, no, no, it’s just like, don’t be self righteous, don’t come into a conversation, like telling people what you think they should do. And I should say, also, like, I’m not always the greatest practitioner. This like I write, I write about a lot of people who are much better at this in their day to day lives than I am. But

Jenny Splitter

just have to say like, day to day, this is me, all right, conversate about anything. I’m doing so great. Listen, then next day, just be like, you are wrong, you know.

Ana Bradley

I don’t, I didn’t tend to have the good days, I’m just like the you are wrong person. So I try to leave the talking to other people.

Brandon Keim

Like, you know, when just one anecdote I wanted to share that I love so um, so there are some foxes in my neighborhood, who I quite like, and sometimes this is difficult, right? Because I really love the groundhogs too, and I feel in a special kinship for the groundhogs and I’m seeing the foxes eat a lot of groundhogs and that can be something that can be difficult to make peace with. But that being said, I really, really appreciate the foxes as well. And so a few years ago, when when there were box cubs, some somewhere nearby and the parents were just hunting all the time, and like Fox parents work so hard to care for their children. You know, I would, I would pick up squirrels who had been run over on on a road somewhere and just, you know, leave them down in a corner of the driveway for the for the foxes to find try to make things a little bit easier for them. Um, so anyways, like, I was here, here in Bangor, Maine, where I lived, I had just pulled over by the side of the road, and, you know, gone out to pick up a squirrel living flat and in the middle. And this guy came out of his house, and he had, like, you know, he just shouted at me, he’s like, Hey, what are you doing? You know, and, and he had and it wasn’t like, what are you doing? I was like, no, what are you doing? And, and he had the whole phenotype, right? Like he was, you know, just this, like, you know, like big, burly, hard looking dude who I just thought it was gonna be, you know, giving me some, you know, either giving me the Get out of my neighborhood treatment, or else just like, What are you doing you weirdo pick, you know, picking up this animal this is, you know, but I told him what I was doing. And he and he said, in the next thing he said he was just like, he was like, I you know, I see squirrels get run over here all the time. And it breaks my heart to see their bodies just out there in the road like that. And so what he does is he’ll just go out and and gather the body and bury them in his garden behind behind his house. And like, and it was just like, every kind of every assumption I had about where the interaction was gonna go, it was the opposite of that. And and I think about that a lot, right? Like, and just, you know, not not leaping to conclusions about what other people think and being being open to just how we all are, we all feel such a connection with the animals and, and we do the best, the best we can and sometimes we just need permission to be open about it.

Ana Bradley

That’s so true. That’s a really beautiful story. I mean, I guess we’re kind of sadly running out of time. I feel like we could keep talking about all of these things for hours and hours. I had one question which I am curious about in the course of writing this book, because I feel like you’re so experienced and you’ve done, you spent so long in this space, but in the process of Right and Meet The Neighbors. Was there anything about animal behavior or sentience or whatever? Like that surprised you? Was there any kind of like, Hey, I never knew that, you know, this animal could do this or anything like that, that stood out.

Brandon Keim

I mean, so there’s so, so many so many of those moments. But I think maybe the going to say maybe what I came to appreciate most that I didn’t fully appreciate before, was just how much companionship means to so many animals. And maybe that should be obvious, right? Maybe Maybe I should have thought of that in the first place. But, uh, but I think, you know, I didn’t, you know, things like, like, friendship, you know, thinking, thinking of other animals as having, you know, friends and social ties, and kind of community norms that are meaningful. I didn’t, I hadn’t fully thought through the social dimension, or fully, fully learned about the social dimension of things and thought through what that meant. Maybe as much, you know, as much as I had, you know, these sorts of other questions of self awareness, or whether an animal feels pain or not, or thinks about the future, and so on. And just like one of one beautiful kind of vein of research that I hope to write about much more in the future, is scientists who have found ways of very unobtrusively and non invasively, tracking the movement of flocks of birds as they migrate. And, you know, there’s this one study that was done with their named Honey, honey eaters, they are bead Anyways, these, these birds are flying, like many 1000s of miles. And they’re, they’re going the whole way, with the same companions, right, or if they get separated along the way, then they’re managing to reunite at the end. And just like, you know, like, migration is the most incredible thing, right? Like the, you know, to be this, this small, delicate creature who finds their way across half the globe, you know, orienting by by geomagnetic winds and the stars and, you know, eating what they can along the way, I mean, it’s just the most incredible journey. And then to think about that journey is also one in which, you know, they’re making it with their family, with their own with their people. And that just makes it so much more resonant to me.

Ana Bradley

That’s so I just a quick follow up here. Like, I came across my desk this morning article in the Financial Times. That was from January this year, about using AI to track animal intelligence and using it to decode, you know, conversations and monitor them in this kind of unintrusive way that, as you as you’re talking about, Have you have you looked at, like, progression in AI for this kind of thing before? What are your thoughts on on that?

Brandon Keim

A little bit, I’ll say that, like the, you know, there’s just kind of this like, whole world of like, AI hype, and I think sometimes that also gets extended to, you know, using AI to, to look at what the animals do not so much in the sense that AI techniques can’t offer something new. But like, like, the work that scientists have done on animal communication in the last few decades, is extraordinary. And we’ve learned so much and like, the idea that AI can help illuminate more shouldn’t, like, shouldn’t come at the expense of appreciating just how much we do understand now. That so that being said, like a I think AI tools can be really useful. And not just in analyzing animal vocalizations, which is how they’re usually portrayed. And I think this is a function, you know, of being sort of, inter anthropomorphic, in in a negative way, where, you know, we think of, we put so much importance on language and so much of our own communication takes takes the form of language. And so naturally, you know, when we think of understanding what other animals communicate, we’re like, oh, well, what are they saying? But for many species, you know, sent is such an important form of communication, and then body language and gesture are incredibly important. And there are researchers who were, were, you know, looking at it those other modalities through through the lens of AI as well and especially a primatologist named Katherine who biter. Her whole Bader who, who studies chimpanzee gestures, and I saw a presentation recently where, you know, she’s been taking some of these tools and using them to analyze the gestures they make. And oh, it’s just it’s just remarkable.

Jenny Splitter

Like debating is I have so many different questions on our time, but I guess um, no, I think I’m a Well, okay, I did want to at least ask you about kind of like your thoughts on on how journalists cover animals generally, because I guess for me, it was, like, you know, I’m sort of, in this food ag world. And I also am I started essentially was very committed to sort of, kind of stripping out emotional language, I guess from our writing, I was like, I want us to sound like everyone else, essentially, like, I really had that as like, you know, kind of a strong feeling in my head, and then, or whatever, wherever my feelings came from. But and then like, you know, when I came back, I started sort of reading more journalism about wild animals. And I was like, This is so strange, because it’s like, almost the exact opposite of what I’m talking about. But if we were to write about farm animals, that way, it would be like, weird vegan shit, you know? And so I, you, I mean, I think I do a nice job in the book of kind of just like, you know, just talking about all of the animals. And I wonder if you think we’ll see more of that. Or if you felt like a little self conscious doing, like, where do you think kind of the state of how we write about farm animals, I guess is, you know, or how you maybe think about that your yourself? The question?

Brandon Keim

Yeah, that is, that is a really big question. So I think it’s, you know, so, so I very much commiserate with the dilemma that you faced in wanting to, you know, right, quote, unquote, emotionally, or, yeah, you know, about animals and, and feeling like, you had to sound like everybody else, because we do live in an ecosystem where, like, if I, if I think, you know, if I think global warming is terrible, and really, really hope that humanity finds a way to, to not overheat the earth. You know, like, that’s okay, right? Like, that’s, I can still write about climate change, nobody is going to, you know, no editor, no reader is going to call that, you know, a meaningful conflict of interest. But if I were the fact that I don’t think we should eat animals on on my sleeve, or at least on animals who live a life that I would have been happy to live, you know, then well, that is a conflict of interest. That’s kind of, you know, that’s kind of weird. You’re, you’re self conscious about it. And, and, and then at the same time, it’s completely customary, like, if you’re, you know, if you’re a food writer, and you’re like, here’s my article about the best hot dogs in America, nobody, nobody calls that a conflict of interest that you don’t think of those of those hot dogs as coming from any animal who was a somewhat so there’s this. So there’s this double standard that makes writing about farmed animals. Very difficult. And, you know, of course, if you’re only writing for the people who are already in your circle, then then it’s no trouble at all. But if you hope to, to reach outside of that, then, you know, then then you have to wrestle with that. And, and I think, you know, or at least I’m hopeful that, that the needle is moving in that it is becoming more more permissible to feature, you know, to include the voices of people to include the voices of animal advocates in the stories. And this is certainly by no means universal yet. And it is still like unendingly frustrating to me, that publications will have, you know, articles about the intelligence of animals and articles specifically about the intelligence of farmed animals. And yet, if a story is about farmed animals trade policy, or you know, or just food and recipes, then the perspectives heard when talking about animal intelligence, are not included in the perspectives heard in those stories about trade policy, or we’re cooking recipes. You know, and I think that’s, that’s an inconsistency It doesn’t it doesn’t really hold water intellectually. And I will pull that that over time. It’ll be you know, over time the recorded the reporting will be better and that yeah, that’s that’s a that’s an uphill it’s an uphill battle, especially with farmed animals. I think it’s a bit it’s a bit easier with wild with wild animals at least.

Ana Bradley

Is this something that you feel you will be working on next, like thinking about your next steps post this book? Like, what’s your What are your plans?

Brandon Keim

Oh, I mean, so there’s, so there’s endless stories I have about animal intelligence that I hope I’ll find people who will pay me to write them And then also some other stories that are just about nature and things that are not about animal intelligence that I’d like to get into. But I think a lot about how, how much I would enjoy, you know, a deep dive into sort of what, like, so this is, you know, I know this is, so this is going to be something, I think that that may be that your vegan listeners and viewers will understandably not maybe be a fan of, but like, you know, like, are, is it at all possible to have relationships with the animals that are consumptive, but also genuinely, truly respect them, and give them lives that you and I would want to lead? I think, you know, just in as much as is, as much as I would love for the whole world to go vegan tomorrow, as in as much as that is not going to happen. I think this question of what are truly acceptable relationships with the animals who are used is a powerful one. And, you know, I love like, I love the sanctuary movement, and I volunteer every week, in my nearby sanctuary. And I think, you know, the moral, the moral imperative to support those is enormous, especially for people who like me, like, in the first 40 years of my life, I ate so many animals, and the least I can do to give back a little, a little to them is to take care of, of, you know, of some farmed animals. And, um, but that being said, you know, I think there’s, there’s a limit on how far sanctuaries can go. And there is that kind of internal tension, where sanctuaries are possible, because people are able to donate to support them, and, you know, pay the salaries of the staff who worked so hard to care for those animals. And, you know, they can, you know, in a sense, they’re, they’re not, quote unquote, scalable. So I think so I think sanctuaries give this wonderful, beautiful window into relationships with farmed animals that don’t otherwise exist, and, and are so kinder and more just beyond that, then sort of the question of what, yeah, like, sort of what, what relationships, what other relationships are possible, that, you know, have had those elements of respecting for the animals and caring for the animals and allowing them to live full lives in intact social groups, you know, for their own benefit, and not for our own profit? You know, is it possible to take all that and still say, okay, and, you know, we will, you know, we will use their fur and eat their flesh? And maybe it’s not right, like, maybe, maybe those two visions are just completely opposed. And they can’t be reconciled. But I would like to explore that space.

Ana Bradley

Yeah, and investigate those communities where they believe they are having those relationships, and what the end of life for the animals looks like, you know, all of these aspects within it. That sounds super interesting. And yeah, I look forward to following up with you over time with with with that your investigations. Brandon, where can people get your book

Brandon Keim

at your favorite local bookseller, or, or, of course, Amazon or Barnes and Noble, or all the other big booksellers, as well. And thank you so much for bringing me on here to talk about it. I really, really appreciate it. I’ve enjoyed talking to you.

Ana Bradley

We’ve really enjoyed it. And I am so grateful for the work that you do and I fully recommend this book and your first book to anybody who’s interested in anything that you said in this conversation and and more. And Jenny, I’m sure you need to feel so.

Jenny Splitter

Thanks so much for doing this. It was a great conversation.